Read about an early feminist, an ardent baseball player, and efforts to reclaimed neglected Black neighborhoods — and the memories they hold.

by WALTER staff

Torch Bearer by Colony Little

Anna Julia Cooper was born into slavery in Raleigh in 1858 and died in Washington, D.C., in 1964. In her more than 100 years, she was educated at St. Augustine’s University, Oberlin College, and the Sorbonne in Paris. A published writer and an ardent supporter of Black feminism, she published one of the earliest texts that identified the unique intersectional issues Black women faced fighting for equality and suffrage while being relegated to tertiary footnotes in the struggle for civil rights. Today, her writing can be found on page 27 of all U.S. passports: “The cause of freedom is not the cause of a race or a sect, a party or a class — it is the cause of humankind, the very birthright of humanity.” Read More >>

Saving Chavis by Courtney Napier

Chavis Park was created as a park for Black North Carolinians by the WPA — and was embraced as a space for after-church picnics, community center classes, and sports, Chavis was built mostly as a means to a segregated end. “The saga of Chavis Park mirrors the story of the American South: it encompasses the promise of emancipation and the horrors of Jim Crow. It contains the complicated history of progress through the Works Progress Administration program and, nearly 70 years later, the HOPE VI Project,” writes Courtney Napier. “On June 12 of last year, Chavis Park started a new chapter of its story: one that honors the resilience and perseverance of the Black community in the face of it all.” Read More>>

A Legacy of Generosity by Courtney Napier

For over 100 years, a neighborhood in West Raleigh near Meredith College has stood stronger, together thanks to Black leadership. Method village was formed in 1872 by Jesse Mason and Isaac O’Kelly, who purchased 69 acres that were parceled and sold to newly freed Black families. By the turn of the century, Method held over fifty households., and by 1923, the Berry O’Kelly High School, named after a successful local businessman, was one of only three high schools for Black students that was accredited by the state, as well as a gathering place for the children of Method, many of whom are still in the neighborhood. When the City of Raleigh annexed Method in 1960 as part of the expansion of the inner Beltline, it meant Method would finally have city utilities and paved roads. But it also threatened to erase the community’s identity. Here’s how neighborhood activists have worked to preserve and celebrate their neighborhood. Read more >>

Oberlin Rising Memorial by Liza Roberts

Located in a historic section of the Village District (formerly known as Cameron Village), Oberlin Rising is an installment of five earthcast pillars by Thomas Sayre. They commemorate Oberlin Village, a once-vibrant freedman’s community in Raleigh. Oberlin was developed shortly after emancipation, and was host to a lively community of middle and upper-class black families. Over the course of several decades, Oberlin gave birth to countless trailblazers and history makers, including Joseph Holt, the first student to attempt to challenge desegregation in Raleigh Schools, and Wilson W. Morgan, who was among the first black men to serve in the House of Representatives. Though the neighborhood’s character eroded over time, largely due to the impacts of Jim Crow and the annexation of the land into the city of Raleigh for commercial development in the 1960s, the pillars of Oberlin Rising stand as a soaring reminder of the indomitable spirit of the village, and a memorial to those who made it what it was. Read More >>

Saint Augustine’s University at 150 by Henry Gargin

Saint Augustine’s University was founded by a group of 11 Episcopal clergymen who, after the Civil War, saw the need to provide education and infrastructure to the approximately 4 million recently freed slaves who had never had the benefit of formal schooling. It’s one of two Raleigh HBCUs – Shaw University, a Baptist institution, is the other. It began as a place of opportunity for those denied it elsewhere and the school’s role has since changed in form, though not in spirit. The school has evolved, still serving a marginalized population, but it’s a subset of students who need the structural and cultural opportunities Saint Augustine’s can provide. The obstacles that persist for black students seeking a college degree – and there are many – no longer include exclusion from top institutions like Duke or UNC-Chapel Hill. Black college students have choices now, and it’s up to places like Saint Augustine’s to convince them that historically Black spaces still hold value. Read More >>

Saving a School by Lori D. Wiggins

Following emancipation, education in North Carolina for the Black community remained severely underfunded and neglected by state governments. One answer to that: the Panther Branch School. Founded in 1926, this elementary school opened with the help of philanthropist Julius Rosenwald, president of the Sears-Roebuck Company, inspired by his relationship with Booker T. Washington. The school became host to a tight-knit group of children united through the newfound opportunity. The school shut down in 1967 and the building fell to disrepair in the decades that followed, but new preservation efforts have ignited in recent years, driven by the students who once walked its halls. The community-driven preservation of the building is a remarkable testament to the lasting impact the school had, and a reminder of the importance of preserving histories that often go untold Read More >>

Welcome to Black Main Street by Colony Little

Raleigh’s Black Main Street can be found on Hargett Street, including the Grand United Order of the Odd Fellows Building, the Delany-Evans Building, the Lightner Arcade Hotel among others. The area was once a bustling center of Black-owned businesses, before the rise of suburban shopping centers and urban renewal. Artist TJ Mundy painted a series of 5 murals in April 2021 along this street as historical markers outside of these prominent buildings. After being inspired by the protests demanding justice for George Floyd, Mundy wanted to shine a light on the Black businesses that lined this segregated corridor of Downtown — which thrived in spite of Jim Crow laws that were designed to disenfranchise them. This unique mural project invites residents and visitors to acquaint themselves with the neighborhood’s past. Read More >>

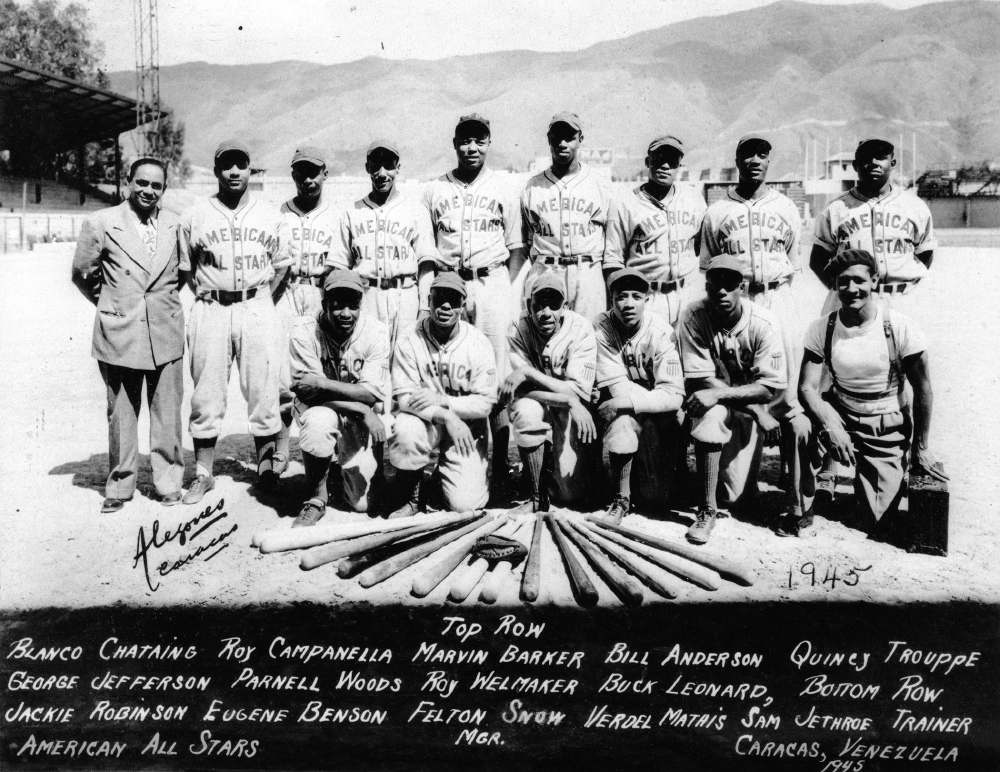

Team Leaders by Hampton Williams Hofer

Inside the North Carolina Museum of History, modest artifacts speak to the resilience of Black Athletes in America. One of those artifacts is the baseball uniform of Buck Lenoard, a Black player who overcame obstacle after obstacle to play the game. He was the Negro League’s all-star first baseman an incredible 12 times. Leonard led the Homestead (Pennsylvania) Grays to nine consecutive pennants from 1937 to 1945, the Negro League’s all-star first baseman a 12 times. As a kid growing up in Rocky Mount, he’d sneak over to the baseball field of the local white team and watch through the fence. Once he was arrested peeking through that fence, but he never lost his love of the game. With no Black high school in Rocky Mount, Leonard went to work for the rail station after eighth grade, eventually playing semi professional baseball on the side, until he worked his way up to the Grays, widely considered one of the best teams in Negro League history. Read More >>

The Story Behind the Walnut Creek Wetland Center by Ayn-Monique Klahre

In the 1890s, the Brimley brothers, the scientists who spearheaded the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, asked the young son of a Black farmer where to find the best local wildlife. He pointed them towards the Walnut Creek wetlands, and even showed them where to find the nest of a Black Rail, an elusive marsh bird. But over the next 100 years, the area became polluted, a victim of unfair development practices and neglect. But in the 1990s, St. Ambrose Episcopal Church started a series of stream cleanups that led to a hard-fought community effort to reclaim the wetlands and create a nature center to serve the Southeast Raleigh community. Read more >>