This Raleigh native discusses the journey to releasing her first book, Historic Black Neighborhoods of Raleigh.

by Courtney Napier | photography by Phillip Loken

Carmen Cauthen is a native Raleighite, down to her birth at Saint Agnes Hospital in 1960. She grew up in several historic Black neighborhoods, including Washington Terrace, South Park and Idlewild, and lived as an adult in Oberlin Village. Cauthen was raised by parents that prized community, which they served faithfully as a pharmacist and school teacher.

Cauthen fostered her unique affection for the stories of the elders she regularly interacted with in her childhood home, her father’s pharmacies and her mother’s political and social justice meetings. After graduating from North Carolina State University, Cauthen became a Journal Clerk for the House of Representatives of the North Carolina General Assembly, from which she retired after 20 years. Her experience at the NCGA sharpened her research skills — and gave her a unique perspective on the impact that history can have on everyday life.

Cauthen became concerned with Wake County’s rising property taxes and development and their impact on long-neglected neighborhoods. In 2019, she started working with a local affordable housing advocacy organization, Wake County Housing Justice Coalition (WCHJC).

That work became a gateway into researching her first love, Raleigh’s Black history. Since then, she has become a leading historian on Raleigh’s Black communities. Her first book is Historic Black Neighborhoods of Raleigh, which was released in late 2022 through Arcadia Publishing.

How did you become an expert in Raleigh’s historic black neighborhoods?

I grew up in Raleigh’s Black neighborhoods, and I’ve loved history since I was a young girl. But the opportunity for in-depth research came quite recently.

I was working with the WCHJC in 2019. I hate being old, but I was the oldest person in the room! I would talk about things that I remembered about Southeast Raleigh.

I had done some personal research for fun about Southeast Raleigh, and I had found two digitized research papers. The first, “The Evolution of Raleigh’s African-American Neighborhoods in the 19th and 20th Centuries,” was written by Richard L. Mattson, Ph.D., a preservation consultant with Mattson, Alexander and Associates, based in Charlotte. He was hired for a massive architecture survey second by the Raleigh Historic Districts Commission (RHDC) between 1987 and 1992.

The second paper was the master’s thesis of Karl Edward Larson entitled “Separate Reality: The Development of Racial Segregation in Raleigh, North Carolina, 1865-1915” written in 1983. Larson’s thesis was an important resource for Mattson’s work and is referenced several times.

The members of the WCHJC were concerned with the inadequacy of the proposed affordable housing bond, so we planned a campaign to educate the public about this. I was asked to speak on the history of Southeast Raleigh.

I believe that when it’s time to speak on history, you go as far back as you can go. So I dug up these two papers by Larson and Mattson, and in rereading them I realized that Wake County had 12 freedmen’s villages. They were all outside of the original boundaries of the city: North, South, East and West Streets. Several of these made up what became Southeast Raleigh.

These freedman’s villages were created when slavery ended and plantations had to be sold. When investors bought these properties, they divided the properties into little tiny lots, and they put little tiny houses on them for formerly enslaved people to rent or lease.

Bigger properties had houses that were on a third of an acre, but most were on a tenth of an acre or less. Those lots never changed sizes as they became part of Wake County’s plot plan.

I started to think economically: We build our generational wealth for the most part through our homes. These freedmen were already behind because they just came out of slavery.

And if the only house you could purchase was on a tenth of an acre, as opposed to somebody who was able to build the same-sized house on an acre or more — now you’re even more behind, because this is a legal plot, and it’s all you have to work with.

So how did your book come about?

In December of 2020, Heather Leah, a fellow Raleigh native, historian and reporter for WRAL’s “Hidden History” segment, reached out to the WCHJC and asked if there was somebody who could talk about the freedmen’s villages for a web story in development.

I didn’t think anything was coming of it, but after the story was published in January 2021, she reached out again. Heather was speaking on the freedmen’s villages at the North Carolina Museum of History the following month, and she asked me if I would do it with her. I said, Okay! About 30 minutes after we finished the event, I got an email from an editor at Arcadia Publishing. She had attended the talk, and asked if I would be willing to write a book on Raleigh’s Black neighborhoods.

I thought I would easily get it done by June — four months to complete my first draft. But that’s not what happened.

How did you start?

I started with my copy of a book called Culture Town: Life in Raleigh’s African American Communities, which was published in 1993 by the RHDC as a culmination of an architecture survey. Upon rereading the book, I saw that there were about 60 people who were quoted.

I looked online for the interview transcripts or recordings, and found that there were actually 74 of them. On my first pass, I was able to find four of the transcripts, which were interviews with Manuel H. and Myrtle Creecy Crockett, Jesse Copeland, Clarence Lightner and John Winters. I had known all of them.

Anyway, Lightner’s interview transcript was 47 pages long, and the others were about 30 pages apiece. But in Culture Town, there were only two or three paragraphs from each person.

What happened to the rest of the interviews?

I reached out to Ernest Dollar at the City of Raleigh Museum, and they had had some students at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte transcribe some of the interviews through UNC’s Southern Oral History Program. He sent me those and, as I was reading them, I realized how incomplete they were.

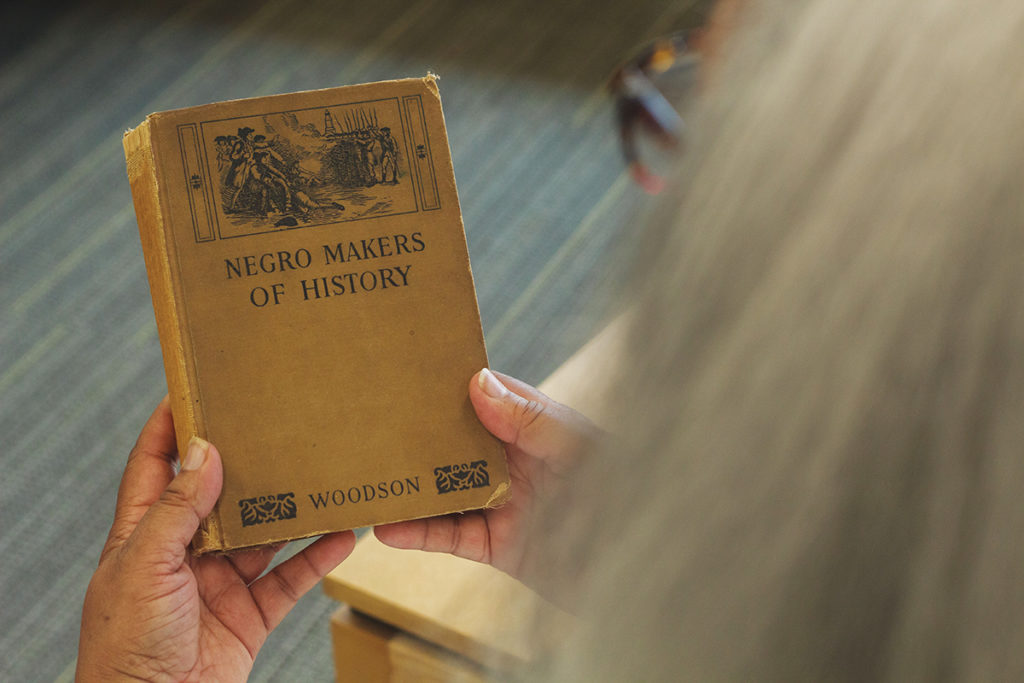

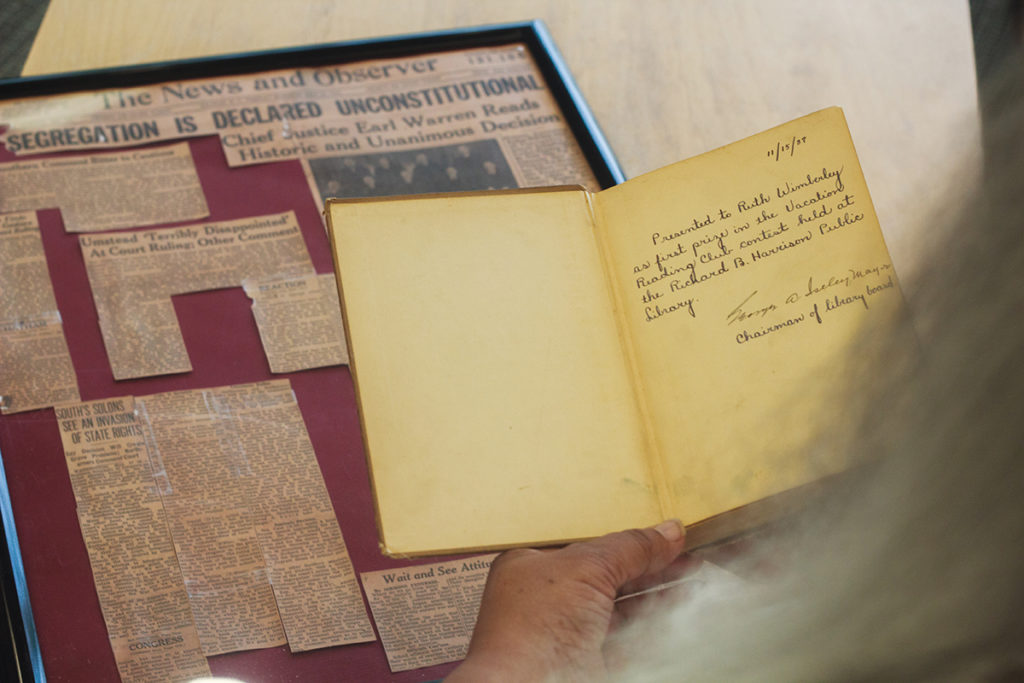

The students weren’t familiar with Raleigh, so many names and locations were spelled incorrectly. If you were trying to use this information as research, you couldn’t do it. I asked Wanda Cox-Bailey, who’s a former librarian at Richard B. Harrison Library, to help me find the original tapes and the rest of the transcripts. That October, we found them at the library.

So it took eight months to simply locate the information needed? Why so long?

Older information, no matter who it is about, is not digitized. Also, much of the research is done in academia, and when the professors retire or pass away, oftentimes the access to their research goes with them. I was able to find the names of some of these books because they were mentioned in WAKE: Capital County of North Carolina, volumes 1 and 2, reference books written by Elizabeth Reid Murray. She was considered the foremost historian of Wake County’s early history. But, like Murray’s books and Culture Town, many of these reference books are out of print.

When I finally gathered all of my research materials, it was time to write. Having never written a book, I reached for the skills I gathered as a college student to build my approach: I bought hundreds of notecards, then started writing down the information I needed by hand and created a catalog system that allowed me to reach the right notecard when I came to that place in my book. Yes, I wrote a good part of this book by hand. I’m that old school!

What was the most rewarding part of writing this book?

It’s been that I can help our kids recognize that they came from somewhere important and that our people have done things. Too often, children — Black children in depressed communities in particular — hear, You haven’t done nothing, you come from nothing, you ain’t gonna be nothing. And that’s not true! It is so not true. But kids begin to believe that. And their parents might not be equipped to tell them otherwise, because they were told the same thing when they were young.

We come from a strong, resilient, proud people. We are fortunate to be from a town with two Black colleges and a middle class that grew up in between them. Everybody who’s Black here didn’t come from poverty! Black people in Raleigh came out of slavery and started businesses, churches, colleges and primary schools. Making this critical information accessible to these families — our families — is an incredible reward.

Why do you think the book will resonate today?

Often, when I’m talking to somebody about affordable housing, they don’t understand why the gentrification piece is so important — that there’s cultural significance to every displaced family, every demolished building, every redeveloped neighborhood. Gentrification is all about overlooking this fact. That’s why they need to learn the history of Southeast Raleigh and Raleigh’s historically Black neighborhoods.

Most don’t know that there was a 300-acre college, Latta University, in Oberlin Village. Most don’t know that the Lincolnville community was where Carter-Finley’s parking lot is today. The people in that community were forced to sell. Hargett Street is known for being our Black Main Street, but many of those businesses were originally on Fayetteville Street.

They moved to Hargett Street because of segregation and Jim Crow. It’s important to know who you are and where you came from, even if you don’t like what it is, because it shapes who you are.

What’s next for you?

This book sparked a passion to write more. We need more books! We need to know more about what Black women in Raleigh and beyond have accomplished. I want to write a book about my mother, Cliffornia Wimberley. She was an amazing woman, but like many amazing Black women around the world, we only know little bits and pieces of their stories.

That was the rewarding part of writing about Raleigh’s Black neighborhoods, learning my purpose. It took 60-plus years for it to be revealed. And as I look back, I can see every step that God put in place, whether I followed it exactly or not. But it still led me here.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

This article originally appeared in the February 2023 issue of WALTER magazine.