From the Hell Creek Formation in Montana to the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences — here’s what went into bringing the Dueling Dinosaurs to Their New Home.

by Jamie Dement \ photography by Nathan Cooper and Justin Kase Conder

The Hell Creek Formation, near Fort Peck, Montana, is a barren, rocky landscape of sandstone, shale, and clay. It’s an unforgiving land, but one that has preserved layer upon layer of natural history. In the Cretaceous period, 66 million years ago, this area in the southern part of the state was warm, humid and flat — not dissimilar from what, you’d find along the North Carolina Coastal Plain.

Hell Creek has produced some of the most extraordinary and scientifically important dinosaur specimens ever discovered. And it’s here that Clayton Phipps, a local rancher and self-styled dinosaur cowboy, has made a name for himself searching the area for fossils.

Unearthing a Surprise

On a warm June day in 2006, Phipps brought his cousin, Chad O’Connor, for his first fossil hunt, along with Mark Eatman, a colleague he had worked with on other digs, to survey an area of land owned by other private landowners. They found something that would change their lives.

Eatman saw it first. To a seasoned fossil hunter, bone is obvious; it just doesn’t look like sand or rock. There was a pelvis weathering out of the ground, and they could also easily see what appeared to be an articulated femur. The trio noted their location and made the long trek home with big plans to return.

But it was months before anyone could return to really see what they had discovered. After a summer of ranch duties, Phipps and O’Connor returned to the site to start the painstaking process of unearthing what they’d found with a brush and penknife.

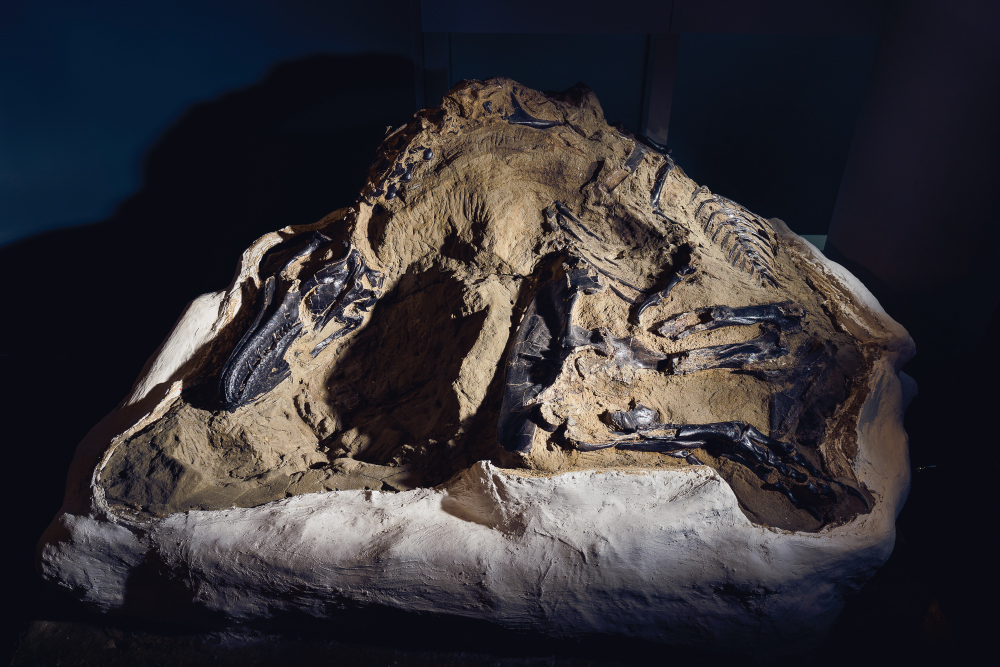

It turned out to be the full skeleton of a Triceratops, a great find for any fossil hunter. With two weeks of backbreaking work behind them, Phipps and his small crew thought they were almost done. They moved on to using heavy equipment to clean up the site around where the Triceratops bones were found.

As Phipps emptied the backhoe bucket of excess dirt — slowly, because folks who work with fossils are always conscious that additional evidence or bone fragments can be found anywhere — he made a second, startling discovery.

Most of the debris in the bucket was light-colored sand and rock, but mixed in were dark fragments. “They looked almost like dark chocolate,” says Phipps. Definitely pieces of bone, but not from the Triceratops a few yards away. Phipps sifted through the contents of the bucket more carefully. He realized that the bones made up a claw. A claw from a meat-eating dinosaur. Buried next to a plant eater.

After three more months of digging and excavation, Phipps had two complete dinosaur skeletons wrested from the earth: the Triceratops and a Tyrannosaurus rex. He brought in a team to prepare the specimens for transportation and storage, then set about the process of getting these unique fossils out into the world.

That journey took longer than expected. Phipps knew the value of what he had found, but he also knew that in order for the dinosaurs to be properly preserved and studied, they would need to be housed in an institution that could handle not just their sheer size — together, they weigh over 30,000 pounds — but also the rigorous research to uncover the whole story. That’s where the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences comes in.

Wondering What’s Next

The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences hosts over a million visitors in a normal year within its downtown Nature Exploration Center and Nature Research Center. For more than a century, it’s been the place to see state-of- the-art exhibits and experience nature and science first-hand. Many of the state’s schoolchildren have their first encounter with fossils and real dinosaur specimens there on field trips.

From its inception, the museum has been a repository of the state’s natural collections, from ancient fossils and naturalist drawings to its growing collection of living specimens. The dozens of scientists, researchers, and educators who work at the museum are leaders in their respective fields and all share a vision for collaborative teaching and hands-on learning.

One of those leaders is paleontologist Dr. Lindsay Zanno. Zanno’s passion for her work and dedication to sharing it with the public are not simply infectious, they’re inspirational. Zanno completed her undergraduate work at the University of New Mexico and her graduate work at the University of Utah. Her work as a paleontologist has taken her all over the globe: from the Field Museum in Chicago to Mongolia and Thailand to vast swaths of the American West.

She works with exploratory teams, usually for months in the field, to track down fossils and study how changing climate and environmental conditions affected life on land during the Cretaceous period. Zanno has discovered the remains of more than a dozen new species, including Siats, one of the largest meat-eating dinosaurs on the continent, and Moros, North America’s tiniest Tyrannosaur. Today she calls Raleigh and the Museum of Natural Sciences home.

The museum’s longtime partnership with North Carolina State University and deep commitment to citizen science were what drew Zanno to the institution, and she has helped grow the already well-known paleontology program over the past decade. She works in a joint appointment between the museum and NC State and leads teams of students into the field every year.

“After being here for six or seven years and seeing how successful of an enterprise the Nature Research Center is, I was asking myself, what’s next for the museum?” says Zanno. “How do we keep pushing the boundaries and being on the leading edge of connecting the public with science? What can we do to take it to the next level?”

Over the years, Zanno had heard about Phipps’ incredible discovery — two fully intact dinosaurs, frozen at a specific moment in time. If the condition of the specimens was even half as good as reported, then the find could be a game-changer: the “Dueling Dinosaurs,” as they had become known, would be among the most complete skeletons ever discovered of two iconic dinosaurs. And the T. rex fossil would be the only complete skeleton of a T. rex known anywhere in the world. These fossils could challenge everything we know about dinosaurs, including how these very famous species interacted. Bringing them to NCMNS would make the museum a global center for paleontological study.

And then there was the mystery: how did these two dinosaurs get buried so close together? “We want to know how these animals died, were they interacting?” says Zanno. “You can imagine how many times in a million years two animals get buried in a moment of time together like that, a predator and prey. It’s so incredibly rare.” Zanno wanted those dinosaurs to head south for good.

So in 2016, Zanno and a team from the museum headed to New York to meet Phipps, who’d been storing the specimens there since 2013, after an unsuccessful attempt to sell them at auction. She wanted to confirm that the dinosaurs were authentic skeletons, in good condition, and that they still had their scientific integrity. It was necessary to confirm that the fossils had been properly removed from the field and cared for while they were prepared for sale in a way that did not destroy the research value of the specimens.

The team also arranged to visit the Hell Creek Formation. The fossils were found on private land, but they needed access to the site to get all the data needed for research, including studying the geography and topography of the area, taking soil and water samples, and looking for any other flora and fauna fossils in the area to understand the world their dinosaurs lived in.

“They are extraordinarily well-preserved specimens of our two most famous and beloved dinosaurs,” Zanno says. “They were first found over a century ago and we still know so little about their basic biology.”

Armed with the knowledge that the Dueling Dinosaurs were indeed as extraordinary as expected, Zanno and then-museum director Emlyn Koster approached the Friends of the Museum about finding a way to bring the dinosaurs to Raleigh permanently. The idea of two new dinosaurs coming to town made the Board sit up and pay attention.

“The Friends were immediately very excited about the prospect of bringing these complete dinosaur specimens to the museum. This is unheard of, right?” says Angela Baker-James, executive director of the Friends. “Having Lindsay and her team be the people who uncover, who unwrap whatever is hidden inside the fossils? It’s just incredible.”

Within weeks, the Friends started a campaign to raise the money to bring the Dueling Dinosaurs to North Carolina. Meanwhile, Zanno and her team started working with the museum’s exhibits team to figure out how to showcase what could be the most important paleontology find of the century.

Taking Down the Glass

Historically, museums have displayed fossils out of reach. They’re discovered in a field, then brought back to a lab, where they can end up buried in a museum or university basement for research. By the time the fossils, or facsimile models made of plastic or epoxy, are reassembled and put on display in a simulated environment or diorama, a visitor is presented with a specimen that has already been exhaustively studied.

But over the past decade, science museums have started building fossil labs in public spaces so visitors can watch scientists at work in real time. But, Zanno noted, there’s still separation between the researchers and the visitors, with almost no direct interaction. Her question became, “Can we really draw people into the process of what science is? Could we take down the glass and bring the public into the process of unveiling the secrets of the Dueling Dinosaurs?” She challenged the exhibits department to come up with an entirely new environment, one where guests can step right into an active research laboratory where work is being done.

“Our goal here is to let the visitor’s imagination run wild,” says Javan Sutton, head of exhibits of the museum. He’s working with HH Architecture in Raleigh and the museum’s exhibits team to bring that idea to life.

Situated inside an extension to the NRC beside the Daily Planet, the Dueling Dinosaurs will be an exhibit experience that will transport visitors 66 million years into the past. To create the space, which is expected in 2022, the museum will embark on an extensive construction project that includes reinforcing the floors

with steel beams to support the 30,000-pound specimens. The center of the exhibit is the actual paleontology lab and the areas before and after the lab will encourage visitors to join in the scientific process and ask their own questions.

“The Dueling Dinosaurs are unlike anything I’ve ever seen, in any museum,” says Eric Dorfman, director and CEO of NCMNS. “We will be performing research in front of, and even with the assistance of, the public. It will be a unique experience for everyone involved.”

It’s an approach that turns the old notion of a museum on its head: not just a place to learn what’s already been discovered, but to be part of the process. “We want the visitor to think of themselves as scientists, as paleontologists,” says senior exhibit developer Wendy Lovelady. “We want them to help us figure out the answers to some of these questions.”

Uncovering Answers….and More Questions

Today, the dinos are in the building, so heavy they can’t even be housed in the same room. But it will still be more than a year before the public gets to see them.

The Triceratops skeleton is so large that it had to be preserved in multiple pieces to move it from the field. The T. rex is all in one piece except for a small tail section, so once they’re on view, visitors can see the entire skeleton in the position the dinosaur died in. Until the new exhibit is completed, guests can view a Triceratops foot in its matrix and jacket and a replica T. rex foot on the second floor of the main building.

Visitors will see the skeletons as they are studied in labs, within the plaster preparations they were brought in from the field. They won’t be fully excavated and assembled, as fossils have been in the past; instead, the paleontologists will use CT scans and imaging to literally look inside the blocks of earth holding the fossils.

“What I love about science, and particularly paleontology, is that you can have a whole set of questions as you dive in, but come up with dozens more as you make your mini-discoveries,” says Zanno. “It’s like a big, unopened Christmas present.”

The museum already knows that fragments of teeth from the T. rex are embedded in the Triceratops. There are skin impressions from the Triceratops on the surrounding stone and octagon-shaped impressions or formations on its frill that can offer clues to skin texture and material. Over the coming years of research, the museum expects to learn about the dinosaurs’ soft tissues, maybe their last meals.

“What would their skin look like on various parts of their skeletons? Did T. rex have feathers?” says Zanno. “We know one broke a finger in its life, one broke its tail, and there’s evidence of diseases — what else can we learn about how these animals lived?”

“I feel blessed to be a part of it all,” says Phipps. He’s particularly pleased with where the Dueling Dinosaurs have landed: not only in a stellar research museum, but in North Carolina. “They have landed in a similar environment to the one they lived in while they were alive. They will feel right at home there.”

At the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, the feeling is mutual. Says Dorfman, “We are all thrilled to have this one-of-a-kind opportunity to house and research one of the most important paleontological discoveries of our time.” It took more than 66 million years, but this unlikely pair has found a welcome resting place in North Carolina.