A pandemic ritual to connect with friends turns into a celebration of the players that give college basketball its true spirit.

By Ed Southern

If you can call it a game, my buddies and I have begun to play: no points or score, no goals or winners, no final horn, no written rules.

Our field of play is a text thread. Our game time is whenever the spirit moves one of us, trusting each other not to be the guy who texts in the middle of the night.

How do we play? Simple: Name an Atlantic Coast Conference men’s basketball player who played between 1982 and 1998.

Why do we play? That might be simple, too.

Malcolm Mackey. John Crotty. Elden Campbell. Tom Sheehey.

The player can’t be too obscure — no checking the internet for walk-ons and benchwarmers — but they can’t be too well-known, either. There’s no fun in naming the first players everyone thinks of when they think of that era of ACC basketball: Michael Jordan, Ralph Sampson, Len Bias, Christian Laettner, Tim Duncan, Vince Carter. Those guys entered the consciousness enough to stick around long after their last March Madness. Their highlights still show up on TV, whenever the ACC or their school or some other advertiser wants to weaponize nostalgia and the idea of tradition. Remember them? Remember that dunk, that shot, that One Shining Moment? Remember how long and how much you have enjoyed this sport, this product?

Our game’s goal is to trigger memories, too. Our point is to call up a name that spent three to four years at or near the forefront of our minds, and then left. To play our game, we name a player whose name and face and number and motion we once thought about a lot, and since haven’t thought of once.

Walt Williams. Kelsey Weems. Pete Chilcutt. Bruce Dalrymple.

Why 1982 to 1998? Those aren’t strict limits, but for us they mark an era. In 1982, UNC won the national title, its first since 1957 and the ACC’s first since NC State’s in 1974, when some of us were toddlers and some of us weren’t yet born. By 1982, we were old enough to remember not just the championship game — Patrick Ewing’s goaltending, Michael Jordan’s jumper, poor Fred Brown’s errant pass to James Worthy — and where we were when we watched it, but that season. We were old enough to be aware of basketball as more than bright, fast colors; the carnival sounds of cheering fans and pep bands; and “Sail with the Pilot,” the ubiquitous jingle of the Jefferson Pilot Corporation, lead sponsor of regional ACC telecasts. We were old enough to know something about how to play basketball. We were old enough to be aware of ACC basketball as a thing unto itself, to begin to absorb something of its weight and meaning in the suburbanizing Sun-Belt North Carolina where we all were born and were growing up.

I was old enough to have had a friend come home with me from school on Quarterfinal Friday of the ACC Tournament, when the teachers fought over the big TV carts from the A/V room, so they and we could watch the games in class. As we waited in our kitchen for his mom to pick him up, he mentioned that his dad was at the Tournament, and had invited him to come, too, but he’d said he’d rather come hang out with me.

“You did!?” my mother, my father, and I all exclaimed, shocked, even a little appalled.

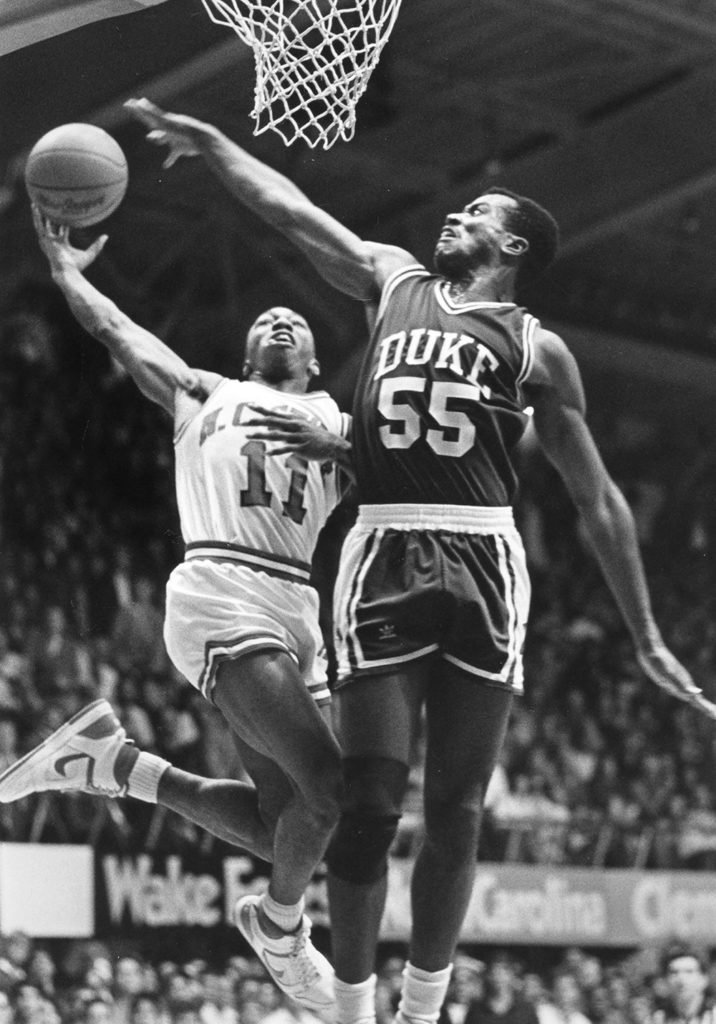

Photo courtesy of NC State Student Media / University Archives Photographs

Jeremy Hyatt. Timo Makkonen. Olden Polynice. Anthony Teachey.

In 1998, the youngest among us graduated from college, from Wake Forest, from the ACC. UNC made the Final Four; Duke, the Elite Eight. By 1998, their rivalry had established its hegemony over the conference, in results but more so in media coverage. A new or casual fan could watch an entire season on ESPN, and be forgiven for failing to realize that Tobacco Road was far longer than the 10 miles of Highway 15/501 between Chapel Hill and Durham. In 1998 Antawn Jamison, who years before had been a Charlotte summer league teammate of my brother’s, won the Naismith, Wooden, and practically every other Player of the Year award. Between Wake’s 1996 ACC title, and Florida State’s in 2012, either UNC or Duke won the Tournament every single year but one. Between 1982 and 2019, ACC teams won 13 national titles, but only 3 of those were won by a team other than the Tar Heels or the Blue Devils. Those famous miles between the Dean Dome and Cameron Indoor sucked all the oxygen out of ACC basketball.

In 1998, Wake Forest’s back-to-back Tournament titles were fresh in our minds, and the Heels/Devils dominance didn’t seem so assured. The ACC hadn’t expanded beyond nine teams, in a fairly cohesive regional spread between College Park and Tallahassee, and so every team still played every other team twice, home and away, each regular season. The Tournament was still only four days, Quarterfinal Friday still intact. Maryland hadn’t left for the Big Ten’s football-driven TV money. Our corner of college basketball still felt like a community, the season like a ritual, a reminder, an assurance through the winters, which still were cold.

Sam Ivy. Keith Gatlin. Mark West. Cal Boyd.

The goal is that spark of recognition, yes, and the quick trip down Memory Lane (which in this case is a spur off Tobacco Road). This little game of ours, though, also serves to strengthen bonds, sustain connections, and — sure — show off a bit. We started playing the week before the 2020-2021 college basketball season began, nine months after the pandemic had shut down the ACC Tournament and cancelled March Madness. We’d seen each other some, at a distance and outdoors, but for the first time in more than a decade none of us had tailgated together, sat in the stands together, watched any games together. We didn’t expect to do so again any time soon, certainly not that basketball season, a season that might not play out to the end, a season they might should not play at all.

We’re a homogenous group of seven, with two pairs of brothers who all went to Wake Forest, plus three Tar Heels. We all are North Carolinians, with roots going back generations. Four have known each other since their teens, when they were counselors together at a Baptist summer camp. Two of those roomed together during graduate school at Duke, and were looking for a third. One of them had a younger brother who knew my younger brother at Wake, and knew he was going to Duke for graduate school, and connected them. I’d hang out when I came to the Triangle for work, and crash on a sofa they still can’t believe I was brave or foolish enough to sleep on.

Four of us now live in Winston-Salem, one in Raleigh, one in Tryon, one outside Goldsboro. All of us are white, straight, cis, middle class, professional.

All of us are sports fans. We have other interests, even passions, and often have long and deep conversations about books, music, movies, whatever: Part of what I value about these friends is their taste, their intellect, their ability to talk about Walker Percy, Ron Rash, Rhiannon Giddens, Superchunk, Terrence Malick, and Mike Krzyzewski, over multiple beers in a single gathering, or over the miles of a day hike.

Most of us, in fact, hardly follow ACC basketball anymore. The four Deacons have suffered through a decade of dreadfulness, Wake fielding teams who played with so little balance or spacing that they looked like pickup players who’d ended up together at random, not even knowing one another’s names. Conference expansion has made college basketball feel reduced, ditched the home-and-away ritual of the season, made Tobacco Road feel like a cul-de-sac. The one-and-done rule has stolen any sense of connection to the biggest stars: I sometimes forget that Zion Williamson and Kyrie Irving spent a season at Duke.

The other five, in fact, follow European football, particularly the English Premier League, as avidly as any sport now, and spend the winter watching more NBA than ACC. (Four of us grew up playing soccer; one went to a Division II school on a soccer scholarship.)

Still and always, though, ACC basketball conjures up our childhoods, calls back to where we came from. We all still live in North Carolina, each an easy drive from the place where we grew up. Where we grew up, though, is as gone from us as if we had come from overseas.

Craig Neal. Alaa Abdelnaby. Delaney Rudd.

You probably think I’m thinking of where we cheered on The Dukes of Hazzard, tearing around the backroads in a souped-up Dodge they called the “General Lee,” the Confederate battle flag painted on the roof, the opening bars of “Dixie” blaring when they blew the horn. You might think I’m thinking of where Dad went to work while Mom stayed home and had dinner ready by 6.

But I, speaking only for myself, am thinking of the place where we cheered on The Dukes of Hazzard, each of them “just a good ol’ boy . . . fightin’ the system like a true modern-day Robin Hood.” I’m thinking of the woods and fields and creeks that that friend and I played in after school, in between games on Quarterfinal Friday, and how they’re long since cleared and leveled and culverted for McMansions.

I don’t blame you. Lots of people have confused the one for the other, the loss of the one for the loss of the other. Most of the North Carolina we grew up in should be gone — but it’s not. Some of that North Carolina we should have kept — but it’s gone.

Robert Brickey. Billy King. Cozell McQueen. Tony Massenburg.

If we wanted to remember the highlights, the indelible moments, we’d text each other those: Lorenzo’s put-back, Laettner’s turnaround, Randolph’s crossover 3. If we wanted to remember the highlights, we’d text each other YouTube links.

We already remember the highlights — the thrills, the shocks — and will until our memories fail, which is why they’re highlights in the first place. We want to remember more. We want to remember the shag carpet we sat on in front of the console TVs. We want to remember the urgent squeak of those lumbering A/V carts when our teachers wheeled them into the room at a trot, triumphant and eager and a little worried someone might hijack the TV in the hall. We want to remember our whole families gathered around, hanging on every bounce. We want to remember when ACC basketball seemed wondrous, and vital, and ours, belonging to our own backyards.

Scholars and artists recognize and revere this capacity for transportation in other means, food and music and visual representation and rituals of culture and religion. We accept and respect that some media can take us beyond nostalgia and into deep memory, where our animating narratives reside and sometimes re-arrange.

Sports, too, perform this function, serve as a vessel for memory, a comfort for the present, a hope for the future. If W. H. Auden was right that “Every high C accurately struck demolishes the theory that we are the irresponsible puppets of fate or chance,” then what else does a game-winning free throw do? If art is the beautiful expression of human creativity, with the power to stir deep feelings and thoughts, then how can a 360 dunk, a step-back 3, a no-look assist in traffic not be art?

Art demands creativity but also discipline, inspiration and dogged practice, perseverance and courage. So do sports: the courage of a 6-foot-tall guard driving the lane against a 7-foot center, of a player setting his feet to take a charge, of a young person who steps to the line with the game on the line and the eyes of millions upon them.

Maya Angelou once wrote, “Courage is the most important of all the virtues, because without courage you can’t practice any other virtue consistently. You can practice any virtue erratically, but nothing consistently without courage.”

Dr. Angelou also lived the last 32 years of her life in Winston-Salem, teaching at Wake Forest, and in a 2012 letter described herself as “a Tar Heel (but not a Tar Heel).”

Take that, Carolina. You got trash-talked by Maya Angelou.

Tom Hammonds. Joe Smith. Buck Williams. Marc Blucas.

Here, now, I’m supposed to tell you What It Means, tie up all these threads I’ve unwound, make my closing argument that this is more than a flimsy anecdote I’ve overloaded, and our texts are more than a silly game of nostalgia, if we can call them a game at all.

I’m supposed to, but I don’t know that I can. Or, rather, I could, but I don’t know that I want to.

Maybe we started playing this game — if you can call it a game — not just to keep present what we missed and were missing in that year of pandemic, but to remember and even celebrate the courage, the perseverance, the grind of those players who wouldn’t go on to NBA stardom, to shoe deals and sponsorships. Maybe we’re reflecting our privilege. Maybe we just want the smiles of warm nostalgia, like the mid-life men we are. Maybe we want a break from the here, now, and its demands. Maybe we just need the distraction.

Brian Oliver. Bryant Stith. Robert Siler. Chucky Brown.

I don’t know how long we’ll keep it going, this silly game of ours, if you can call it a game. Our lineup, so to speak, is large but not limitless. At some point our memories or the team rosters will run out, nothing left but the all-timers and the internet.

We might stop when the pandemic does, when we can expect to go to games again, or gather together to watch. We might stop when my buddies read this, and give me a hard time for taking something fun and overthinking it.

“Dammit, Ed,” the text will read, “if we wanted to think, we’d send each other the names of professors.”

Steve Hale. Serge Zwikker. Todd Fuller. Junior Burrough.

Or we might keep going for as long as we can. We’re as close now to retirement age as we are to college age, which seems both yesterday and lifetimes ago. Before we know it, then, we might be old men, with canes and Depends, fumbling with our now-unimaginable communications devices, using the names of other men to keep alive our friendships and our memories. I hope those other men will be old, then, too. I hope that we’ll all have the chance to be old.

__

Ed Southern is the executive director of the North Carolina Writers’ Network and the author of Fight Songs: A Story of Love and Sports in a Complicated South. It’s available wherever good books are sold.