An ongoing program from the African American Heritage Commission highlights 50 significant moments and people in our state’s history.

by Jamaul Moore | photographs by Joshua Steadman

As the Civil Rights movement galvanized the United States in the 1950s and 60s, citizens of North Carolina were doing their part to fight for equality. And the North Carolina African American Heritage Commission wants to make sure we know about them.

The AAHC is in the process of installing 50 markers across the state as part of its NC Civil Rights Trail program. Each of the metal signposts will offer a brief story about the significance of the location. The markers will be at sites of protests, churches where activists organized, courthouses, birthplaces of key people and more, with an emphasis on honoring local events and personalities that may not have gotten nationwide attention. “Local stories are often lesser known,” said Adrienne Nirdé, director of the AAHC. “It is important to know what happened, to know our cities weren’t exempted.”

To do this, the AAHC has been working with nonprofits, churches and other organizations over the past three years to nominate sites, gather historical documents and secure permissions. “It’s really about garnering community support,” says Nirdé. “The Civil Rights movement came about through the work of everyday people. Yes, there were plenty of politicians and lawyers involved, but also parents, community members and students, who helped move history forward. It’s wonderful to mark and share these stories, especially while many of them are still with us.” The AAHC is preparing to select locations for the remaining markers, with the next round of applications due Sept. 29.

To date, two markers have been installed in Raleigh, with another coming soon. The Friends of Oberlin Village, a local advocacy group, helped push for one of the markers at the site of sit-ins in 1960. “It serves as a way to commemorate the bravery the students showed that day, as well as the significant impact those students had on the state of North Carolina,” says Heather Doyle, a Friends of Oberlin Village spokesperson. In addition to these two marked spots, the AAHC has identified a few other locations important to the movement as part of its Civil Rights Virtual Trail (find the map at aahc.nc.gov).

So the next time you’re walking around Raleigh, look for the following landmarks, and take some time to think about what happened there. “When we acknowledge these places, we’re saying, yes, your history matters,” says Nirdé.

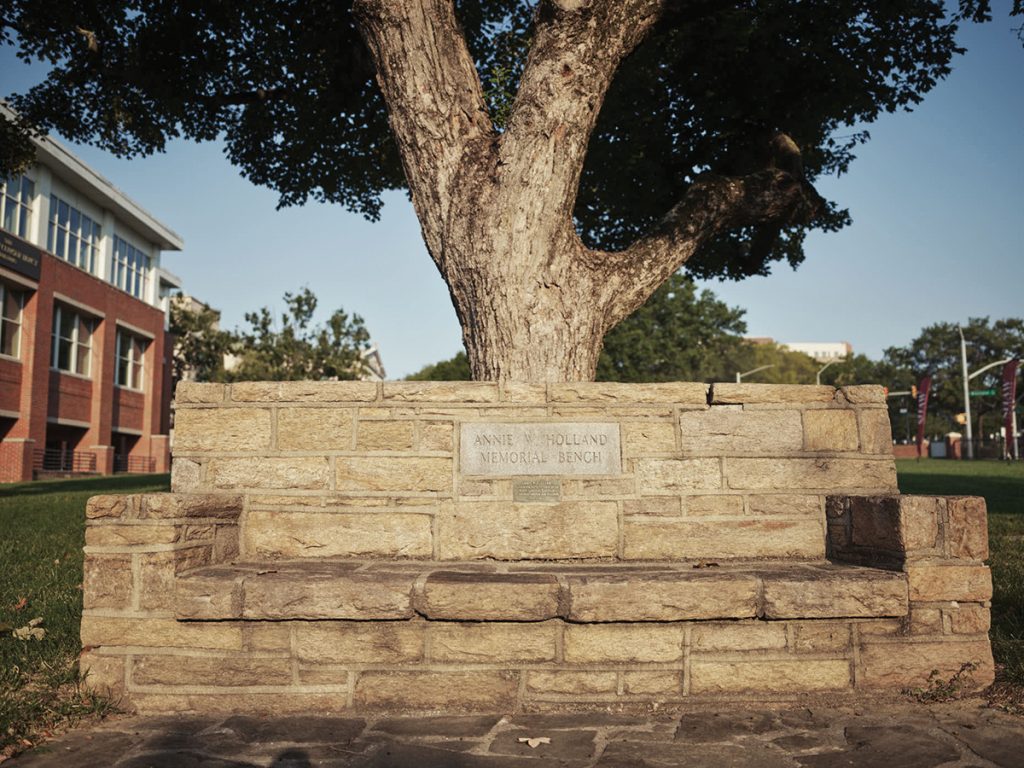

Annie Wealthy Holland

Oak tree and memorial bench at Shaw University, 118 E. South Street

Annie Wealthy Holland (1871-1934) was an educator who served as a state supervisor of Black elementary schools with the Jeanes Fund from 1915 to 1921, which helped support educational programs for African Americans in rural communities from 1908 until 1968, when public schools were integrated. She traveled to each of the North Carolina counties to conduct meetings, organize fund drives and teach demonstration classes to schools to help promote the education of African American children. Holland is best known for founding the North Carolina Congress of Colored Parents and Teachers in 1928, which held its first meeting at Shaw University on April 14 of the same year. The organization was established to raise standards to ensure every child had equal educational opportunities throughout the state. Holland died in 1934, and in her honor, an oak tree was planted at Shaw University on the anniversary of the association’s founding, in 1938. While Holland was not alive during the years of the Civil Rights movement, her efforts planted the seed for educational advancements that would provide better opportunities for African Americans. A stone memorial bench now sits under her tree.

Bill Graves Jr.’s Home

Future NC Civil Rights Trail Marker at the Graves-Fields House, 814 Oberlin Road

Willis (Bill) Graves Jr. (1890-1966) was born in Oberlin Village, which at the time was a freedman’s village. His parents built their home and were pillars of the community. Graves attended Saint Augustine’s College and Shaw University, then got his law degree from Howard University School of Law in 1919. Graves settled in Detroit and by the 1940s was a leading legal advocate in the fight against racially restrictive housing. He served as counsel for the Detroit NAACP, working with some of the country’s renowned attorneys on strategies for civil rights litigation. Two of the most famous cases he worked on were Sipes vs. McGhee in 1947 and Shelley vs. Kraemer in 1948. These were seminal cases in unlocking racially restrictive covenants in neighborhoods.

Graves and his law partner, Francis Dent, took Sipes vs. McGhee to the Michigan Supreme Court, which upheld the covenant. On appeal to the United States Supreme Court, this case was joined by Shelley vs. Kraemer, a Missouri case. Thurgood Marshall was the lead attorney, with Graves and Dent as attorneys of record (Marshall went on to become the Supreme Court’s first Black justice). They won the case, arguing that racially restrictive covenants were a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment, which offers equal protection under the law.

This case was the first in several decisions that struck down government actions that enforced racial segregation, including Brown vs. Board of Education six years later. Graves continued to practice law and support the NAACP for more than four decades. He was also the first Black man named to a committee of the Michigan State Bar. In 2019, Graves’ childhood home, one of the last remaining structures from the neighborhood’s time as a freedman’s village, was moved to its new address to avoid demolition for new development. Along with the Rev. Plummer T. Hall House, it now serves as the headquarters for Preservation North Carolina.

Joseph H. Holt Sr. and Elwyna H. Holt’s Residence

NC Civil Rights Trail Marker at Wilson Temple United Methodist Church, 1027 Oberlin Road, near the Holt residence at 1018 Oberlin Road

In 1956, Joseph and Elwyna Holt applied for their son, Joseph H. Holt Jr. (b. 1943), to attend Daniels Junior High School (now Oberlin Middle School). This all-white school was down the street from their home, but Black students in their neighborhood were being sent to John W. Ligon Junior-Senior High School all the way across town. To get there, they had to take city buses — paying the fare — and walk. The Holts were approached by Jesse O. Sanderson, the superintendent of Raleigh schools, to settle for a compromise or trade-off in exchange for withdrawing their application. Instead, they took it to court.

This lawsuit, Holt vs. City of Raleigh School Board, was the first of its kind in both Raleigh and Wake County, as it sought to challenge public school segregation in court. Even though this was two years after the landmark Brown vs. Board of Education had declared segregation of schools unconstitutional, the case was decided in favor of the school board in September 1958 on a legal technicality, based on two pieces of North Carolina legislation, the Pupil Assignment Act and the Pearsall Plan, which had both been purposefully designed to thwart integration. The Holts took the case to the U.S. Supreme Court, but they declined to hear it due to a May 1955 decision to detach itself from further adjudication of cases having to do with pupil assignment issues, remanding them to the lower courts; the case was closed in October 1959. Joseph Jr. graduated from Ligon High School in June 1960, then graduated from Saint Augustine’s College in 1964. But his parents’ efforts inspired citizens in Oberlin Village to continue challenging the legal system for equal educational opportunities and integrated schools.

Five years after Joseph Jr. graduated from college, the Pearsall Plan, which had been used in the Holt decision, was ruled unconstitutional because it violated Brown vs. Board of Education.

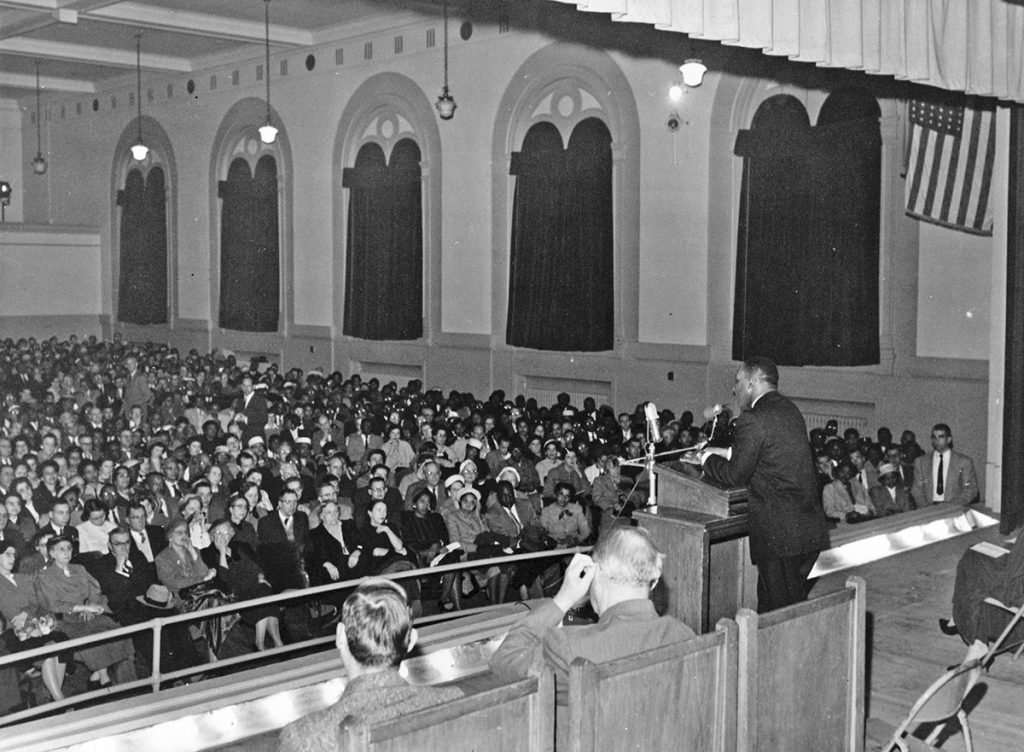

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. visits Raleigh

Broughton High School, 723 St. Marys Street

On Feb 10, 1958, the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. visited Raleigh, having been invited by the United Church, which was then located on Hillsborough Street. But the building could not accommodate as large of a crowd as they anticipated, so they arranged for him to speak in the nearby high school’s auditorium. At the time, Broughton was an all-white school, but the audience of 1,300 included both Black and white guests. There, King delivered his famous speech on “Nonviolence and Racial Justice,” which addressed his philosophy for instigating change through peaceful protest, love and faith. Despite King’s presence and message of integration, the school did not begin integration until 1961, when Myrtle L. Capehart, Dorothy J. Howard and Cynthia E. Williams began to attend.

F.W. Woolworth’s Sit-In

Office building at 224 Fayetteville Street

On Feb. 10, 1960, students from Shaw University and Saint Augustine’s University protested at the F.W. Woolworth’s in downtown Raleigh. This peaceful protest marked the first sit-in at a whites-only lunch counter in the city. The students were inspired by sit-ins in Greensboro, which began on Feb. 1, and others around the country. Police believed that by arresting the student leader, David Forbes, the demonstrations would cease, but the students went ahead with their mission. After this demonstration, various student-led organizations across the city took up similar actions that would promote the Civil Rights movement. This was one of a handful of demonstrations in Raleigh, in which 41 students were arrested and later convicted of criminal trespassing. Raleigh-area students protested at seven other establishments that day, including McLellan’s, Hudson-Belk, Kress, Eckerd’s Drug Store, Walgreens Drug Store, Cromley’s and the Sir Walter Drug Store.

Cameron Village Sit-Ins

NC Civil Trail Marker at 2108 Clark Ave

On the same day as the sit-ins on Fayetteville Street, Black students from Shaw University and Saint Augustine’s University entered the F.W. Woolworth’s at Cameron Village (now known as The Village District). At the time, Black customers were allowed to shop in the stores but were not allowed to sit at the segregated lunch counters. In anticipation of these protests, several establishments in Cameron Village had already closed their lunch counters or stores entirely. During the sit-ins, several students were arrested, and others were verbally assaulted and spat on by opposing patrons. These peaceful protests led to the formation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), a youth political organization founded to capitalize on the success of civil rights demonstrations in the Raleigh area. The SNCC became a major influence in the Civil Rights movement, partaking in the Freedom Rides in 1961 and a voter registration campaign among African Americans throughout the South in 1962.

Felder vs. Harnett County Board of Education and Godwin vs. Johnston County Board of

Education

Terry Sanford Federal Building & US Courthouse, 310 New Bern Avenue

In 1963, 19 Black students filed a suit against the Harnett County school system on grounds of racial separation, led by student Mamie E. Felder. Known as Felder vs. Harnett County Board of Education, the suit sought an order that would transition the existing segregated school system to a nonracial system. After two appeals, the court mandated that they desegregate. The first plan the Harnett County School Board proposed included the closure of three all-Black schools and reassigning their students to predominantly white schools. But the plan did not include eliminating segregation in elementary schools, so it was denied. The school district’s second plan included elementary schools and was implemented for the 1968-69 school year. A few years after Harnett County students brought their case to course, 19 plaintiffs in Johnston County did the same. In 1968, James Godwin and other Black parents filed a suit against Johnston County public schools and the North Carolina State Board of Education on the grounds of racial discrimination.

A year later, in 1969, the court ruled that the Pearsall Plan — the state’s attempt to delay integration in public schools, first used in the Holt v. City of Raleigh School Board case in 1956 — was unconstitutional, as it violated Brown v. Board of Education. The court also ruled that the state of North Carolina was responsible for coming up with a statewide plan to desegregate schools, rather than it being the responsibility of individual counties. With this ruling, the court forced the Johnston County Board of Education and city school boards to devise a practical plan to desegregate schools, which became fully integrated in 1971.

The Hyde County Civil Rights and School Peace Protest in March 1969. The News & Observer Negative collection, from the State Archives of North Carolina.

This article was originally published in the September 2023 issue of WALTER magazine.