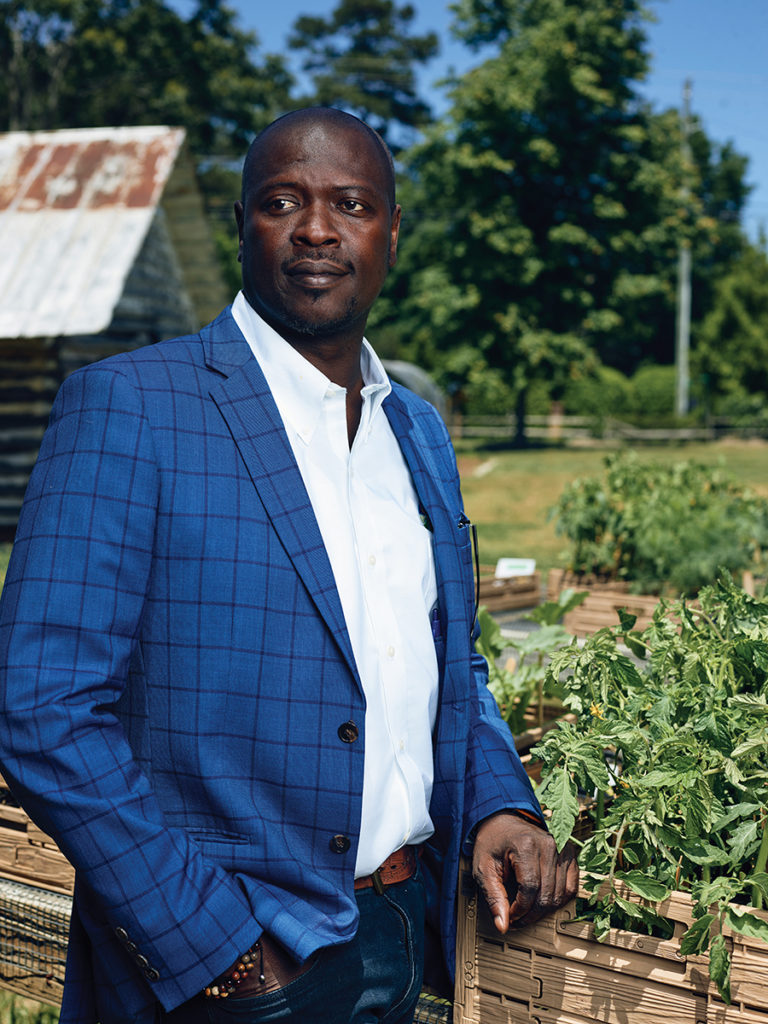

At the helm of the Inter-Faith Food Shuttle, Ron Pringle taps his own history to address food insecurity in a meaningful way.

by Lori D. R. Wiggins | photography by Joshua Steadman

The Inter-Faith Food Shuttle works to feed citizens in need, relieving hunger and restoring hope. At the helm of the nonprofit food bank since May 2020 is president and CEO L. Ron Pringle, whose leadership delivers a “stew” of expertise, compassion and a personal sense of responsibility.

It’s a rich blend nurtured in Pringle as a child growing up in Ridgeville, South Carolina, a town of a little more than 2,000 people in the coastal low country. It’s a place where rich Gullah traditions survive and thrive — with intention. It’s a place that preserves its roots of West African language and culture, from cuisine, storytelling and art, to music, fishing and farming. It’s a welcoming place, Pringle says, where neighbors help neighbors.

We recently sat down with Pringle to learn what energizes his mission to fill bellies and deliver more than meals. The following conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Who is L. Ron Pringle?

I am — as I’ve always told everyone who’s asked — a simple, country boy from the low country of South Carolina.

How did that lead you to become president and CEO of the Inter-Faith Food Shuttle?

Culture, food, growing up on a farm; having that background and work ethic really defined who I am today. Working with my hands, growing our own food, being a part of a community, and being part of a culture surrounded by food means it was always harvest season; family-gathering time, celebration time. So I understand how important it is. That’s my childhood connection. I can relate to so many families now who feel they don’t have that or that they are struggling to maintain that. It makes my responsibility that much more important.

What was your introduction to food banking?

Growing up, I never knew I was one of those children in a food-insecure position. My mother died at 36, and my dad had four young children. I grew up right next door to my grandparents. My grandmother was in charge of a summer feeding program. We would often go down to the food bank and pick up food for everyone in the neighborhood. We received that food as well.

Did that set your sights on a career in the food bank industry?

Since I was 7 years old, I wanted to be an Air Force pilot. I put everything into that. I signed up at 16 and was waived in at 17. Then I found out I’m colorblind and that I would never be a pilot. So I served in the chaplaincy as an assistant chaplain. That melted into the pot and continued to make this stew of who I am. There, I learned even more about service, about commitment, about caring for my neighbors.

When did you realize food insecurity was your story, too?

After I got out of the Air Force and moved back home, I heard the food bank in Charleston was looking for a warehouse worker. I applied. After the interview, the director of the food bank told me, I’m going to give you an opportunity. Later on, one day, I listened to him speak to a civic group about hunger awareness; how hunger is an issue and how the face of hunger is not just the homeless population but it’s also working families. He gave an example of a single parent who lost a spouse and relied on a food bank. Had it been 13 years earlier, he would have been telling my story.

How did the revelation affect you?

In my mind, that’s when it switched from being an opportunity to being a responsibility. It was my responsibility to continue this work because I was the success story of what happens when food is present. I’ve seen what happens, what children go through, when food is not present. I realized they didn’t have the same pillars in life that I had. I was able to be a child, able to hope, to dream, to seek after something, to become something. When food is not present, children don’t have those things. Their pillars become worry, insecurity, anger, frustration — and then they’re labeled. What child at 8 understands the psychology of hunger and how it affects them? They don’t know about fresh food, fresh produce. When those things are not accessible, it’s Ramen, crackers and sugar-filled things, because struggling parents and young parents are trying to stretch a dollar. They grow up with health-care outcomes that could have been prevented, that become challenges in their lives forever. This is a cycle. It’s about breaking a cycle. Hunger, it’s not the problem, but the result of a problem.

What brought you to North Carolina?

The Food Bank of Eastern NC. Accessing food is something I know how to do well and the organization needed that skill set, so, once again, it became a responsibility for me. I worked with them for eight years and became the food director there, began to lead the organization forward, and had the unfortunate experience of going through Hurricane Florence and Hurricane Matthew. Robeson County was one of the hardest hit areas in the state. It was life-changing. I saw the need for food assistance differently, how people were affected and how disproportionate it was — and I saw that it wasn’t an overnight fix. You can provide a meal, but that doesn’t solve the issue. You have to ask: Why are people in the line in the first place? It’s so much more than just having access, or just having independence.

That’s a heavy load. How’d you rebound?

I took a break from food banking and consulted on infrastructure projects. Then Covid hit, and I felt responsible, like, I was on the sidelines saying, Coach, put me in! I know how to do this! During that time, I saw the opportunity, or responsibility, at the Inter-Faith Food Shuttle, and I was excited to be a part of the work one of the founders, Jill Bullard, had been doing for so many years in addressing root causes, moving people on a path to self-sufficiency; work I’ve wanted to engage in.

What did COVID reveal about food insecurity?

Covid amplified a message that people like myself in food justice have been screaming for a very long time. When you see people in food lines and people dying that look like you, and people who are not of color, too, it makes the numbers really resonate. It’s impossible to ignore the inequities and systemic barriers, a systemic design, that keep the gap present. Covid exposed that the practices in place were not benefitting as much as we thought they were. Our intentions were good in making sure food was on the table, but what we saw and what we heard is, Thank you for the sweet potatoes, but I don’t know what to do with them. It felt good to give them food, but it felt horrible that they couldn’t use it. This is where our work became more intentional. I began to look at what worked for me: what worked was my grandmother. She had a program in our community that served our community and made sure children in that community had food on the table.

How are you leading the Food Shuttle’s “post”-COVID response?

We had to reimagine our food system framework. We began to look at my grandmother, at the representative of the community, as part of the solution: this person could be a local farmer, or a teacher, or someone working at a government agency, or a senior who lives there. We removed them from the center and made them part of the circle so they’re included in the conversations about what their community needs. We found out some people don’t need food boxes — they needed refrigeration capacity. And that’s different from the community across town that says, We can use food, thank you, but we have a culture we want to live on, recipes we want to pass down. They want food that reflects their heritage, ingredients they grew up using. It’s not always food recipes, but it’s conversations they have around the table — they find strength in that. The end result of what I’m trying to do is a healthier lifestyle; new habits, new foods and tips on how to prepare that food in a healthier way, how to read nutrition labels, how food is medicine and how to get the vitamins we need through food. If I’m not being intentional, I’m not improving the quality of life for our neighbors.

How can any of us pitch in?

Be a neighbor. As a neighbor, you understand because you talk to each other as neighbors. As a neighbor, your view of this situation looks different. That takes a collective effort on our part. This is not an issue for Inter-Faith alone. We’re a neighbor in this framework, too. A neighbor would say, What do you need? Become advocates to help us tell this story. Get involved. Be a part of the solution. That’s a neighbor bringing what they have to the feast.

__

This article originally appeared in the June 2022 issue of WALTER Magazine.

Pingback: 20+ things to do in June in and around Raleigh - WALTER Magazine