For 50 years, Carolina Tiger Rescue has been devoted to the care and conservation of lions, tigers and other species at its sanctuary near Pittsboro.

by Genie Safriet| photography by Bob Karp

It’s twilight at Carolina Tiger Rescue, a time when the animals are active. Roman, a male adult lion with a huge, tawny mane, playfully nips at his enclosure mate, a female named Reina. Somewhere within the 67-acre sanctuary, an unseen tiger roars. The two lions respond with their deep-throated, oofing calls.

Intimidated by Roman’s calm, steady gaze, guests may not notice his tray of fresh water, the remnants of his healthy chicken dinner or that his favorite spot, on top of his den box, is carefully preserved. Each of these comforts is the work of the dedicated staff and volunteers at Carolina Tiger.

Carolina Tiger is a wildlife sanctuary near Pittsboro. It has roots in the Carnivore Evolutionary Research Institute, which was founded in 1973 by University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill professor and geneticist Dr. Michael Bleyman.

That organization became the Carnivore Preservation Trust (CPT) in 1981, with a mission to maintain a viable population of species essential to the survival of their ecosystem. In 2009, the name was changed to Carolina Tiger Rescue, with the mission of saving and protecting wild cats both in captivity and in the wild and eliminating their exploitation by humans.

Here, they provide safe homes for more than 50 animals, including tigers, cougars, bobcats and coatimundis, to live out their natural lives.

Each day at Carolina Tiger begins with keepers driving through the sanctuary to confirm that all the animals are secure before other staff or volunteers enter. Twice a day, keepers give animals medications like pills hidden in meat or fruit.

The site team handles sanctuary maintenance and improvements and coordinates with keepers on projects that enhance the animals’ quality of life.

For example, Shailah, a white tiger, has mobility issues, so the team built low, easily accessible platforms for her. Volunteers also help with daily enrichment that prevents boredom: animals might find their dinner hidden inside a cardboard box, smell their favorite perfume on a hanging ball, or see themselves in a mirror.

An army of more than 150 volunteers assist with the day’s work, including feeding, watering, enclosure cleaning and construction projects, as well as leading tours and manning the gift shop.

Carolina Tiger is a nonbreeding, no-contact sanctuary. Almost all the animals have come from private individuals or closed animal facilities. Many animals, like Beau — an orphaned, wild-caught cougar — are traumatized when they arrive.

“I tell the animals, It’s going to get better and you will have everything you need,” says assistant director Kathryn Bertok.

Because Beau had not been around people, he was initially quarantined long enough for him to get used to humans in that controlled environment. When he moved to an enclosure, Beau was only visited by keepers at first. But three years later, he’s gained enough confidence to be on the tour route.

Each of the volunteers is intensely trained by staffers, and each of the staffers is cross trained in other roles. “You get to listen and learn and be part of all different areas of the organization,” says senior keeper Lauren Humphries. Volunteer coordinator Maryssa Hill manages volunteer orientation, but she also helps provide medical care for some of the animals on-site.

Education director Katie Cannon helps with day-to-day animal care, in addition to her role creating Facebook Live content and coordinating the summer camp and classes. The staffers are proud of this culture of teamwork. “People come to work here for the animals, and they stay here for the people,” says Bertok.

Because keepers see the same animals every day, they are quick to notice any changes in behavior and proactively handle medical or emotional issues. A partially blind tiger named Nitro kept scraping his nose when he ran into his enclosure fence, so the keepers laid a sand track by the fence so he could tell when it was nearby. “We watched him figure it out. He did remarkably well and stopped running into the fence,” says Bertok. (Nitro has since passed away.) Development director Susan King Cope feels most connected to Tasha, a female tiger who was rescued from a small traveling zoo:

“At first Tasha was timid and would hide behind a tree, especially from men. But over time, she became more comfortable — even talkative.”

Accepting a new animal at Carolina Tiger is a lifetime commitment. “Any species we rescue has to be one that we have already worked with. They also have requirements such as diet and housing that are the same as species we’ve worked with or that we can demonstrate to the board that we can care for responsibly,” says Humphries. Working with rescues often means going through painstaking measures to develop a rapport with an animal.

Caprichio, the largest tiger in the facility at nearly 500 pounds, arrived at Carolina Tiger with metabolic bone disease caused by malnutrition at a cub-petting facility. To manage it, he’ll need pain medications and subcutaneous fluids for the rest of his life.

But, as Bertok says, “These are wild animals, you can’t grab their muzzle and put a pill down their throat! They have to be willing participants in their medical care.“

So Hill trained Caprichio to come when she calls him, lie down next to his enclosure fence, and remain calm for 15 minutes while fluid is injected under his skin. It took four months of training, once a day, five days a week.

“My connection with Caprichio is something I’m grateful for every day,” says Hill. “It makes my heart grow multiple times larger.”

Except when medically necessary, Carolina Tiger follows strict no-contact safety protocols. For example, if Samar, a tiger, charges at the fence near where a volunteer is changing his water, the volunteer knows to look down, not react and wait for Samar to leave.

Every enclosure has multiple segments and animals are coaxed with calling or treats to shift to an isolated area when the main segment needs cleaning or enrichment. Before going into the main area, volunteers and staff verbally confirm with each other that an animal is shifted and it’s safe to enter.

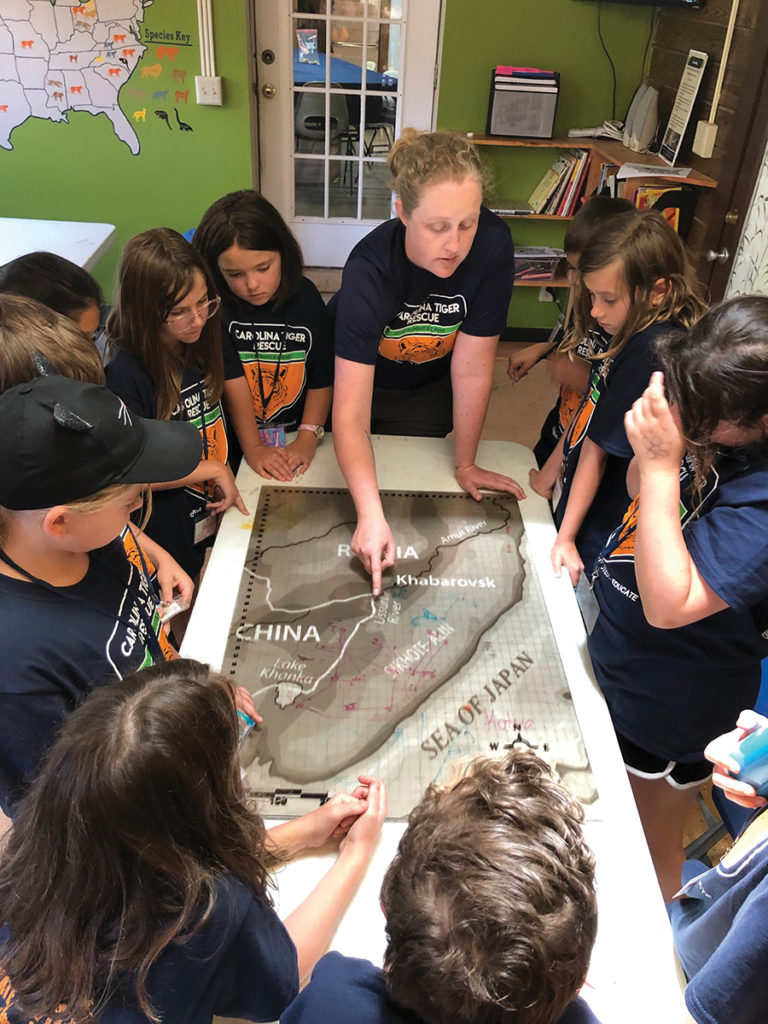

Carolina Tiger also offers educational programs including tours, summer camps and internships. Guides lead more than 13,000 visitors each year through the sanctuary and tell them each animal’s story.

“Visitors come to understand what the animals have endured before getting here,” says donor engagement director Heidi Zangara. “One tour can change something about the way they behave or believe.”

For example, nationwide education efforts about the inappropriateness of owning these animals led to the Big Cat Public Safety Act at the end of 2022, bipartisan legislation that prohibits the private possession of big cats and bans public contact with the animals (such as cub-petting facilities).

Youths from third grade through high school can attend summer camp, where they learn how changes in their lifestyles can affect animals in captivity or watch a tiger create a “pawcasso” print with nontoxic paint. Adults who are considering a career with animals can apply for a hands-on internship.

During the 12-week, full-time program, interns are mentored by keepers as they research wildlife issues, learn about animal care and sanctuary and rescue processes and receive a final evaluation. Bertok, the assistant director, started at Carolina Tiger 23 years ago as an intern.

Recently, after a strenuous, multiyear approval process, Carolina Tiger welcomed two wolves, Caroline and Mist, as part of the Red Wolf Species Survival Plan (SSP). Unlike the other residents, these critically endangered animals native to North Carolina may eventually be released into the wild.

In the meantime, hearing about the wolves in the sanctuary (visitors will never see them — they are isolated in the back of the sanctuary to have as little contact with people as possible) will offer a chance for visitors to understand the urgency of the situation.

“The public needs to understand what is going on with red wolves because they are in our backyard,” says Humphries.

As Cannon says, “It’s pretty amazing to be a voice for these animals.”

This article originally appeared in the March 2023 issue of WALTER magazine.