In this new story from the best selling North Carolina author, a young boy recounts a somber ceremony gone awry.

by Clyde Edgerton | illustration by David Stanley

1977, Hurt, Tennessee

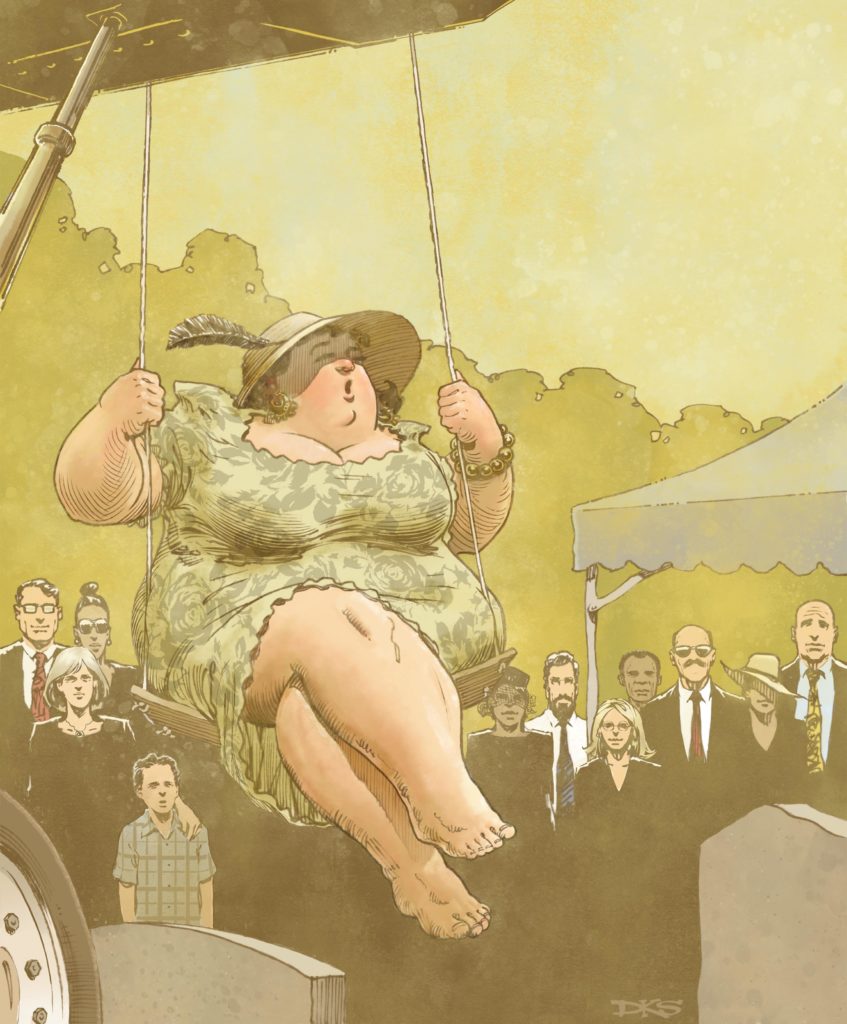

A great big lady goes under the funeral tent in her high heels and sings “How Great Thou Art.” She just belts it out. She’s wearing glasses with thick, black rims. And she’s got on a brown hat with a black feather. It’s Mrs. Britt’s funeral and Mrs. Britt is a hundred years old. Or was a hundred years old.

This is my first funeral in the Funeral Militia, and I don’t want to do anything wrong.

Jimbo Summerlin is the captain and he graduated from high school last year and everybody else in the Funeral Militia is about the same age as him. I’m in the fourth grade. There are seven of us here today. The Quaker’s Son is the head of the Funeral Militia and he works at the nuclear bomb place and had to be there today. He’s the oldest one and his granddaddy was a famous Quaker.

The big lady is singing the song in a real big way.

If we join the Funeral Militia though we sign a contract about never joining the Army. Mama signed mine. This all started ten years ago, right after some people came home from Vietnam.

Jimbo calls cadence when the Funeral Militia marches. Hup, two, three, four. I want to be the caller when I get big enough.

A yellow lightning bolt is on the left sleeve of my uniform, like the others. There’s a plow on the right side. Then it says Funeral Militia in a curve on my front pocket. The uniform is dark blue and the writing and stuff is yellow.

We stand outside the tent while the funeral goes on underneath it — with the family sitting down. We are at Quaker Field. A lot of people stand around outside the tent listening to the song. The seats under the tent are filled up.

The sun is hot, and you can smell the cut grass from where Dennis Warton just finished mowing around the Quaker House and on out here. I will do a drum roll while Lonnie plays the “Red River Valley” on the trumpet at the very end of everything. Lonnie plays a trumpet instead of a bugle. Jimbo does the fold-up-and-present the flag part when it’s a man who has served in the armed forces.

The preacher is talking. Preacher Knight. He is almost all the way bald-headed and has this big Adam’s apple and is a little bit skinny. The whole funeral was at the Methodist church where we sat in the balcony, but they brought Mrs. Britt here to get buried. The pall bearers loaded her into the back end of the hearse while we stood at attention right there close by. A lot of people get buried out here.

A man from Knoxville came to a funeral one time and said the Funeral Militia is against the law.

We stand in two rows just outside the tent. Today, it’s three in the front row and four in the second row. I get to stand at the end of the second row. The reason Jimbo is in the Funeral Militia is because his uncle got killed in World War Two and some other people got killed and the Quaker’s Son started the Funeral Militia like it had been started a long time ago but died out with Hitler and them. Everybody has to look straight ahead while we stand here, and I think about how Jimbo can run really fast and he throws a baseball side-armed when he pitches. Sometimes he chews tobacco. He’s kind of a buddy with the Quaker’s Son.

I hold my drumsticks in my left hand whether I’m at attention or at ease, and my right thumb has to hold tight against the seam on my pants when I’m at attention. My hands go behind me when it’s “at ease.” I have to keep my drum quiet by not hitting it or scraping against it and all that.

The singer lady is real big and like I said has got this brown hat that has a black feather up out of it. She is wearing a tan dress that kind of holds up her front end. She finishes the song. She sang a little bit like a opera singer. She is wearing high heel shoes that I wonder if they are going to stick in the ground. Mama has some shoes that are a little bit high.

This is the biggest funeral I’ve ever seen at Quaker Field.

Mr. Knight is reading a scripture.

When it’s over, Lonnie plays “Red River Valley” while I do the drum part. It’s not hard.

It’s the next day now and I can tell you what happened right after the funeral finished and we did Red River Valley. The opera lady walked right straight into this open grave that was not Mrs. Britt’s grave. That grave was covered up with a great big green rug that looked like grass. Somebody had covered up the open part of the grave instead of the dirt that came out of the grave. They was supposed to just cover up the dirt and put planks over the grave. It was a big mistake. It might have been Dennis or Tiny, or the Mustees.

I had just looked at her when she was kind of walking out from under the tent — because you kind of wanted to look at her with her big padded shoulders, and then I looked at something else, and was waiting for “attention,” and somebody hollered, and when I looked back I noticed that she had just disappeared from the earth.

Everybody started over toward the open grave, except not the people who were already down where the cars were parked. That’s where Mama was. I slid my drum strap off, put the drum down easy, and ran over to the grave where I got up right to the edge of it. The lady was down in there pretty covered up by the rug.

I had thought about how big she was when she was singing “How Great Thou Art.” She had these shoulder pads under her dress on her shoulders like Mama does when she dresses up. She had a big, you know, chest, too. The dress was tan, which I think I said.

Then she got part of the rug all moved back and she’s laying on her back looking up. Baby Jesus in swaddling clothes popped in my head. Her head was kind of rolling back and I figured she’d had the breath knocked out of her because she was looking like that, that look, and her hat was still on and it must have been pinned on or something. It is a brown hat with a black feather, if I didn’t say that. But her glasses were gone with the wind.

Everybody got quiet and I looked around. Preacher Knight was standing there, and Jimbo was kind of kneeling down across the grave from me. I was wondering about what he was thinking, about what he was going to do.

Preacher Knight said to me, “Son, don’t get too close to the edge.” He said it like he might be a little bit mad, so I backed up.

Jimbo didn’t say anything to me, though. He didn’t even look at me. He started talking to the lady. “Are you okay?” he says.

And she breathes kind of deep and says, “Hell, no. I’m not okay. Jesus God.”

With her talking like that, I looked up at Preacher Knight.

He said to her, “Can you stand up?”

“I wouldn’t be on my ass if I could stand up,” she says. She’s from Nashville, and that’s probably why she talks like that.

The preacher just said, “Well . . . “

Some other people were coming back up from down where the cars were parked. But I didn’t see Mama. All the Funeral Militia were standing around and I wondered what Jimbo was going to do.

The preacher says, “That was a wonderful rendition of ‘How Great Thou Art.’”

Floyd says, kind of quiet, “I’ll say how great thou art.”

More people were standing around now, and some more people were coming up.

Mr. Knight says, “Somebody needs to get down in there and get her out.”

I thought about me. I wondered if Jimbo thought about me or about hisself or somebody else.

Lonnie says, “There ain’t no room down there, man.” Lonnie is the biggest one in the Funeral Militia.

“We need a ladder,” said Kenny.

I thought about me going down in there, but I didn’t know if I wanted to or not. I might do something wrong. And I didn’t know the lady. Then I thought about Jimbo maybe choosing me to go down in there and help her out.

“Just pull her up with the tractor bucket,” said Lonnie.

“What?” said Jimbo.

“We can get one of those kids’ swings,” said Lonnie, “from behind the Quaker House and hang it on the bucket with some S hooks. She sits in it and we pull her up.”

“Go get the tractor,” said Jimbo. “The keys is in it.” He was getting to be in charge. I figured he would.

I looked at the preacher and wondered what he would say.

Jimbo said to Carl, “Go get a swing down off that swing set.”

Lonnie was walking on toward the tractor. It sits under a shed in the edge of the woods.

Preacher Knight said, “Can’t we just get a ladder?”

“We’re going to rig up a swing,” says Jimbo. “That way she don’t have to climb out.”

“Wouldn’t a ladder be simpler?” says Preacher Knight.

“I’d be nervous on a ladder,” says the lady up to the preacher. “I might be hurt.”

Everybody was quiet and we heard the tractor crank up down at the edge of the woods.

She was still on her back. I looked around. Some people still didn’t know about what happened because they weren’t coming over.

“This will be easy, ma’am,” said Jimbo. I was across the grave, watching him talk down to her. “We got a tractor coming with a bucket on the front, with hydraulics, and we are going to hang a swing set on it.”

“A bucket?” she says.

“Yes ma’am. Kind of like a big shovel. Like a bulldozer blade, sort of. We are going to hook a swing to it. So you can just sit in it and get lifted right up and out.”

Floyd quiet-like started singing, “Love Lifted Me.” Him and Lonnie get goofy sometimes.

Now the crowd is a little bigger and pretty close up to the grave.

“I think we better get somebody down in there and help you stand up. Is that okay?” said Jimbo. But he didn’t look across at me.

“It’s too bad she didn’t land sitting up,” said Lonnie.

“What?” said the lady.

“I was just talking to Floyd,” Lonnie says.

Then Mrs. Knight, the preacher’s wife, walks up from down where the family cars were — where Mama still was. “What happened?” she says. Then she sees and says, “Oh, my goodness.”

“She fell in the grave,” says Jimbo.

“Oh my goodness,” says Mrs. Knight again, and then she says down into the grave, “Are you okay, Myrtle?”

“I don’t know. I don’t know if I can get up. Is that you, Pauline?” says the lady. “I can’t half see. My glasses fell off. I hope to hell they’re not broke.”

“These boys will get you out,” says Mrs. Knight. “Lord knows they do everything else around here. Where is the Quaker’s Son?”

Lonnie said, “He’s at Oak Ridge today.”

“They’re getting a tractor,” said Mr. Knight. “The boys are getting a tractor.”

“A tractor?” says Mrs. Knight.

Jimbo says, “We’re going to drop down a swing, number one. She sits, number two. We lift her right out. Bingo.”

“Oh,” says Mrs. Knight. “The song was beautiful, Myrtle.”

“Well, thank you. Then I busted my ass.”

I looked up at Mr. Knight. I wondered why she kept saying bad words. I wondered who put the rug over the grave.

Mr. Knight said, “Maybe you could just turn over on your stomach and then get up on your knees and hands?”

Floyd said, “That’s easy for you to say.”

The tractor was coming up with the front-end bucket that you can lift up high. Then in the next minute or two they got it all rigged up so the bucket was up high and the swing was hanging from it.

“How about letting the boy down to help her get set, get that carpet off her?” said Mr. Knight.

Jimbo looked at me, and then at Mr. Knight. And I wondered what he was going to say. But he didn’t say anything. He was going to pick somebody else, I figured.

Then he looked straight at me and here’s what he said, “Go ahead, Gary.” Gary is my cousin’s name. He didn’t know who I was. He said, “Try to get that grass rug — carpet — off her first.”

“Okay,” I said. I wished he’d called me my name, Ozzie. I thought about what if I messed up. “Can I ride the swing down?” I said.

“Good idea,” said Kenny. “Get on there.”

I got in the seat and they let me down and I got off right beside her so I wasn’t standing on her, but I was on the grass rug, and I could smell the inside of the earth and it smelled like fishing worms down in there and mixed in was her perfume. They pulled the swing back up.

The top of the ground was up above my head. I started pulling back on the rug to get it from around her waist and around her feet, but I had to kind of go slow and keep my balance because the grave was so narrow.

“What’s your name, son?” she said.

“Ozzie,” I said. I looked at her and she had makeup on her eyes. I looked up for Jimbo, but he was over at the tractor, I guess. I could hear the tractor motor.

She was helping me kind of get the rug-carpet thing from around her and kind of working herself out of it, and she was on her side, starting to turn over. She stopped moving and looked at me and said, “Ozzie, where did you get that uniform?”

“I’m in the Funeral Militia,” I said.

“What is that?”

“We do military funerals but they ain’t military funerals. They are CC’s. Commemorative Ceremonies, but they are kind of like military funerals, except that’s not what they are.”

She got all the way out from under the rug thing, and while she was getting out, she said, “Did you know Mrs. Britt?”

“Yes ma’am.”

“She was my aunt. She was my daddy’s sister. She was one hundred years old.” Then she looked at her feet. “Can you pull off my damn shoes?”

“Yes ma’am.”

“Thank you, Ozzie. I hope I don’t last a hundred years,” she says. She was working herself up to a sit-up position. “Do you think you can find my glasses?” she said. “I think they might be under me. I hope they’re not broke. Hell, I could just go ahead and get buried now.” She was looking at me and smiled and I liked her even after she said those words.

I looked around, and there were her glasses in the corner nearest by. “Here they are,” I said. I got over to them and picked them up and handed them to her and all the while I was smelling the damp dirt and the perfume.

“Who the hell would dig a grave and then cover it up with a carpet?” she said.

“I don’t know,” I said.

Jimbo said down to her, “If you can sit in the swing, we’ll lift you right out.”

She reached out toward me and I grabbed her hand.

“Grab my elbow,” she said, and I did. She almost pulled me right down on top of her, but she got up to sitting, and then worked her way up to standing. She brushed off the bottom part of her dress.

Somebody up top said, “Can she maybe sing a song from down there?”

Somebody else said, “Sentimental Journey.”

“Ha, ha,” she said, but she wasn’t laughing. “I don’t think so,” she said. “I’ve got some pain in my shoulder,” and she gets in the swing, and is just sitting there. “Mercy, Lord,” she says. The swing starts up and it gets her feet almost up to my knees and one of them S hooks starts slipping up at the top of the bucket thing, sliding down the edge of it, and the swing goes crooked and she’s got one foot on the ground and one in the air and she starts turning in a little circle, holding on to the chains with that one foot on the ground. “Shit,” she says. “What the hell?” She looks up at the tractor.

“My fault, my fault,” yells Kenny. He was driving the tractor. He let the swing down and she slipped out of the swing and stood up there beside me up close, and I smelled the perfume and she turned toward me and I was sort of looking right at her chest, and I remember dancing with Mama at the Ruritan club one time.

Carl told us the S hook was fixed.

“I don’t think she’s going to get out for awhile,” said Lonnie.

They tried again and lifted her up slow with everybody quiet, and you could hear the seat make a tiny cracking sound, and I heard some crows, until she was up there clear of the grave. Then Kenny turned it and swung her slow over the ground and she did a odd thing right then. I could see her top half over the edge of the grave from where I was — she started swinging like you do in a swing, and then she started singing, “Gonna take a sentimental journey. Sentimental journey home.”

I kind of liked her, except she said those ugly words.

They dropped the swing back down and I got in and rode up and out. We didn’t march in formation back to the Quaker House because it was like a whole different day once we got her out. What happened was they got the rug out and we all started walking back to the Quaker House and just when we started, Jimbo walked over to me and didn’t say anything. He turned me around and put his hands under my armpits and lifted me up till I was on his shoulders and he walked me like that all the way to the Quaker House. I held onto his head under his chin. I felt like it was okay that he got my name wrong. I would ask Mama to tell him who I was. It was the end of my first day in the Funeral Militia.

It’s tonight, and all that happened yesterday, and tonight I take Addie out to pee. It’s kind of warm and cloudy. Addie is our dog that stays in the house. I sit on the steps and wonder about what would happen if Addie fell into an open grave. I wonder how many dogs have ever fell into open graves. I get to thinking about all the stars that I can’t see because of the low clouds that are covering up everything.

__

This story originally appeared in the August 2022 issue of WALTER Magazine.