How a self-educated runaway became an advocate for mental health.

by Joel Haas

Dorothea Lynde Dix was more than a hospital or a park.

In fact, Dix Hospital was not actually named for her, and she may have been outraged—or at least, ambivalent—at the grounds’ new use as a park. An examination of her biographies, along with dozens of “memorials”—letters, speeches and notes she penned herself—reveal a woman with an unusual path and sometimes contradictory views.

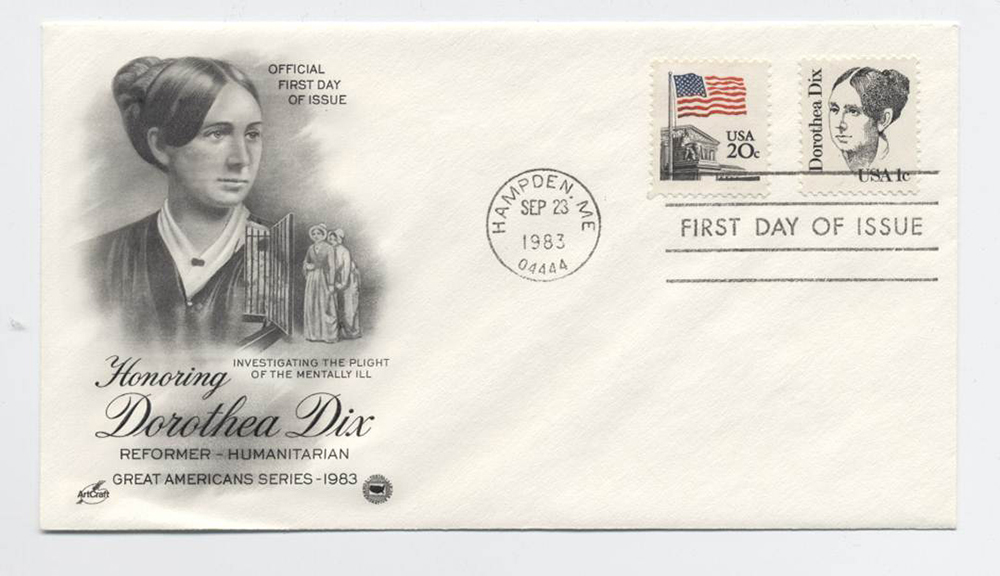

Born in Hampden, Maine in 1802 to an abusive religious fanatic father and a clinically depressed mother indifferent to her daughter, “Dolly” ran away at age 12 to live with her wealthy grandmother in Worcester, Massachusetts. The widow of a prominent Worcester physician and land speculator, Dr. Elijah Dix, this stern, pious taskmaster drilled into her granddaughter that gray areas did not exist.

Self-educated and a voracious reader, Dolly Dix turned to teaching to earn money to bring her two much younger brothers to Worcester. At age 14, she opened a grammar school for girls of wealthy families. Five feet tall and slender, she knew she barely looked a teenager, let alone qualified to teach.

So she lengthened her skirts, wore long sleeved blouses and rolled her abundant hair into tight buns to look older.

It worked. Her school was a success.

Dix was deeply religious, and felt bound to open a free evening school for poor girls. Her perfectionism drove her to rise early, then stay up late grading papers and writing lesson plans. By age 19 she was using one school to support the other, while running her aging grandmother’s estate.

In 1831, she collapsed with exhaustion and coughed blood from tuberculosis. To recover, she took a less onerous job, tutoring the children of a prominent Rhode Island Unitarian preacher, Reverend William Channing. Channing’s family adored her and took her twice with them in summertime to St. Croix, then a Danish colony. While in St. Croix, she expanded her passion for studying nature. She sought out plants, animals, birds—whatever would stand still—to study and illustrate with meticulous watercolors. She continued to collect rocks, plants and any other natural phenomena in her future travels.

In the Caribbean she saw slavery for the first time. Her strict sense of morality gave her a strange outlook: she wrote that she “envied” the slaves’ “carefree attitudes” toward life. (It seems that by her own uptight New England upbringing, it seemed impossible to be both pious and cheerful.) It would be immoral, she declared, for her to teach slaves these principles and thereby make them unhappy. The sinners were the owners, she said, who shirked their Christian duty to teach slaves morality.

As her health recovered, Dix returned to teaching and took up writing. She produced the first handbook of American flowers in 1827, as well as several children’s books. Her book Conversations on Common Things went into 60 printings in her lifetime.

Her health collapsed again in 1836. Physicians recommended she go to Europe. When she arrived in Liverpool, England, friends of Channing, the Rathbones, took her in as part of their family. It was the happiest 18 months of her life, she wrote. She roamed the area recording everything from geology to insects, and even wrote of using the Earl of Rosse’s telescope—then the largest in the world—to study astronomy.

Returning to Massachusetts, Dix learned that her grandmother had died, leaving behind a considerable fortune. Book royalties and this inheritance would enable Dix to live comfortably the rest of her life. Her health had still not completely recovered, so she set about attending to the estate, while reading and writing poetry.

By this time, she was 36, a wealthy spinster, but her intelligence and blunt, imperious manner seemingly dissuaded suitors, according to her biographers.

Chance led her to take up social justice in a field that few people at the time even thought of. She was asked to teach Sunday school at the East Cambridge Women’s Prison. It was only to be a few hours a week, so she accepted.

She left her first Sunday visit horrified. She discovered women with mental illness, charged with no crimes, were nearly naked and fed scraps, chained in cells alongside the criminal population, standing and sleeping in their own waste. Confronted, the warden replied he conformed to all common practices and laws. After all, the women were consigned there by the county as, in the parlance of the time, “looney paupers.”

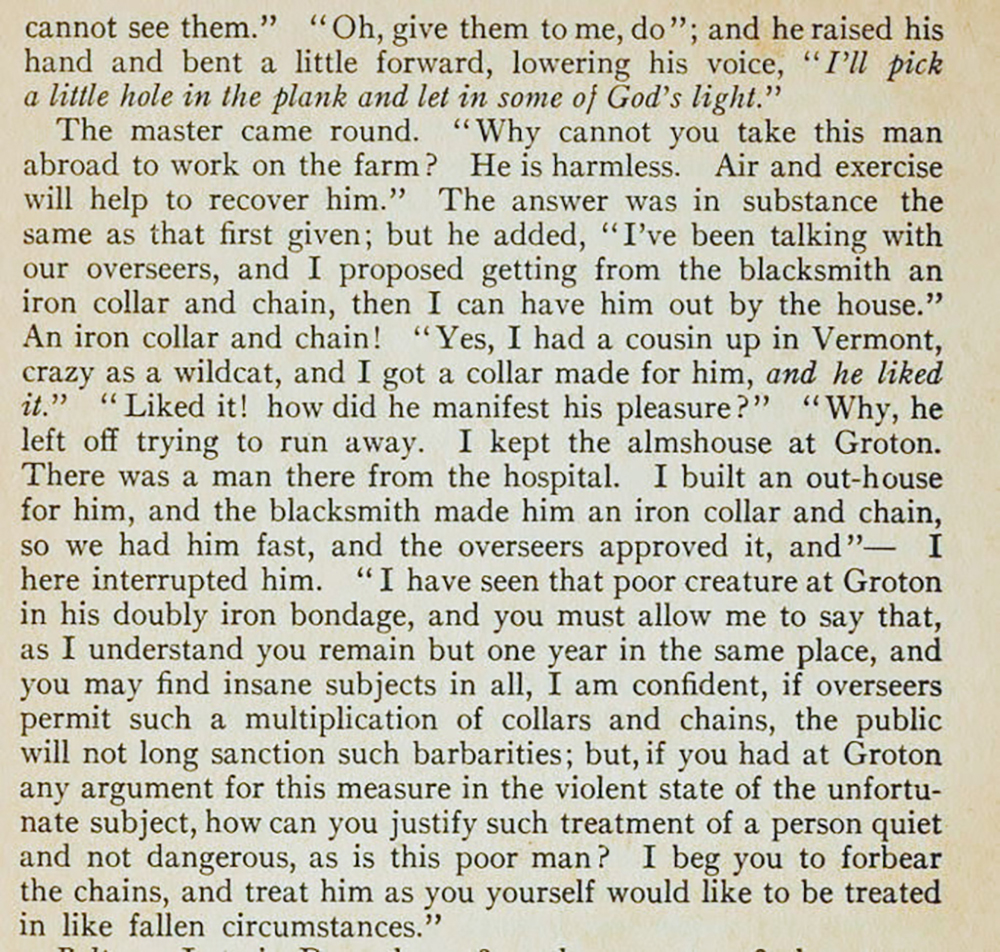

Dix set out to see for herself if the warden was lying. For two years, she visited every jail and poorhouse in the state. The warden wasn’t lying; in some places, conditions were even worse. Between travels, she read widely on the “insane and idiots” (those we now refer to as people who have mental illness and those who are born with intellectual or developmental disabilities) and met some of the leading experts of the day. The public’s prevailing view at the time was these people were unaware of their surroundings—they were people without memories or feelings.

Dix disagreed. She concluded that the people she encountered were very aware of their surroundings and poor treatment and they had memories and feelings like anybody else. “Nobody was ever beaten back into sanity,” she noted.

Whether or not they could be “cured,” Dix believed society had a duty to treat people who have mental illness or who are born with intellectual or developmental disabilities with dignity, kindness and employment.

Dix persuaded a prominent, sympathetic doctor, Dr. S.G. Howe, to write a newspaper article about her findings. The reaction was outrage. Surely, conditions could not be so bad. To disprove her accusations, the Massachusetts legislature launched its own investigation. Finding her report accurate, in 1843, they approved construction of a state hospital.

By then, Dix had set out to see conditions elsewhere. Traveling by boat, rail, wagon, horse and on foot, she visited jails and poorhouses from New Hampshire to Louisiana. When Texas joined the Union, she traveled there. She went to California soon after it became a state. She successfully submitted memorials to legislators asking for funding to build hospitals to treat patients in New Jersey, Illinois, and Pennsylvania.

In 1848, she came to North Carolina. Here, she traveled to 40 counties visiting jails and poorhouses. She persuaded a state senator to present her memorial of findings to the legislature. The reaction was polite, but condescending. The N.C. legislature supported “lower taxes to attract business” over public welfare spending. A Yankee spinster’s advice was not needed. The bill was rejected.

By chance, Dix stayed in the same Raleigh hotel as a legislator named James C. Dobbins and his wife, Louisa, who became deathly ill during her visit. Dix was her constant attendant and nurse, staying with her even after the hospital bill was defeated. On her deathbed, Louisa Dobbins made her husband promise to work to see Dix’s bill passed. Soon after the funeral, Dobbins and Dix walked into the Capitol building’s House chamber together. Dobbins reintroduced Dix’s bill and, keeping his promise, worked to see it passed.

By 1856, Dix Hospital had been completed in Raleigh. Out of modesty, she asked it be named for her physician grandfather, Dr. Elijah Dix. (The name was changed to Dorothea Dix in 2005.)

Leaving Raleigh, she moved on to successfully persuade Alabama and Mississippi to establish state hospitals.

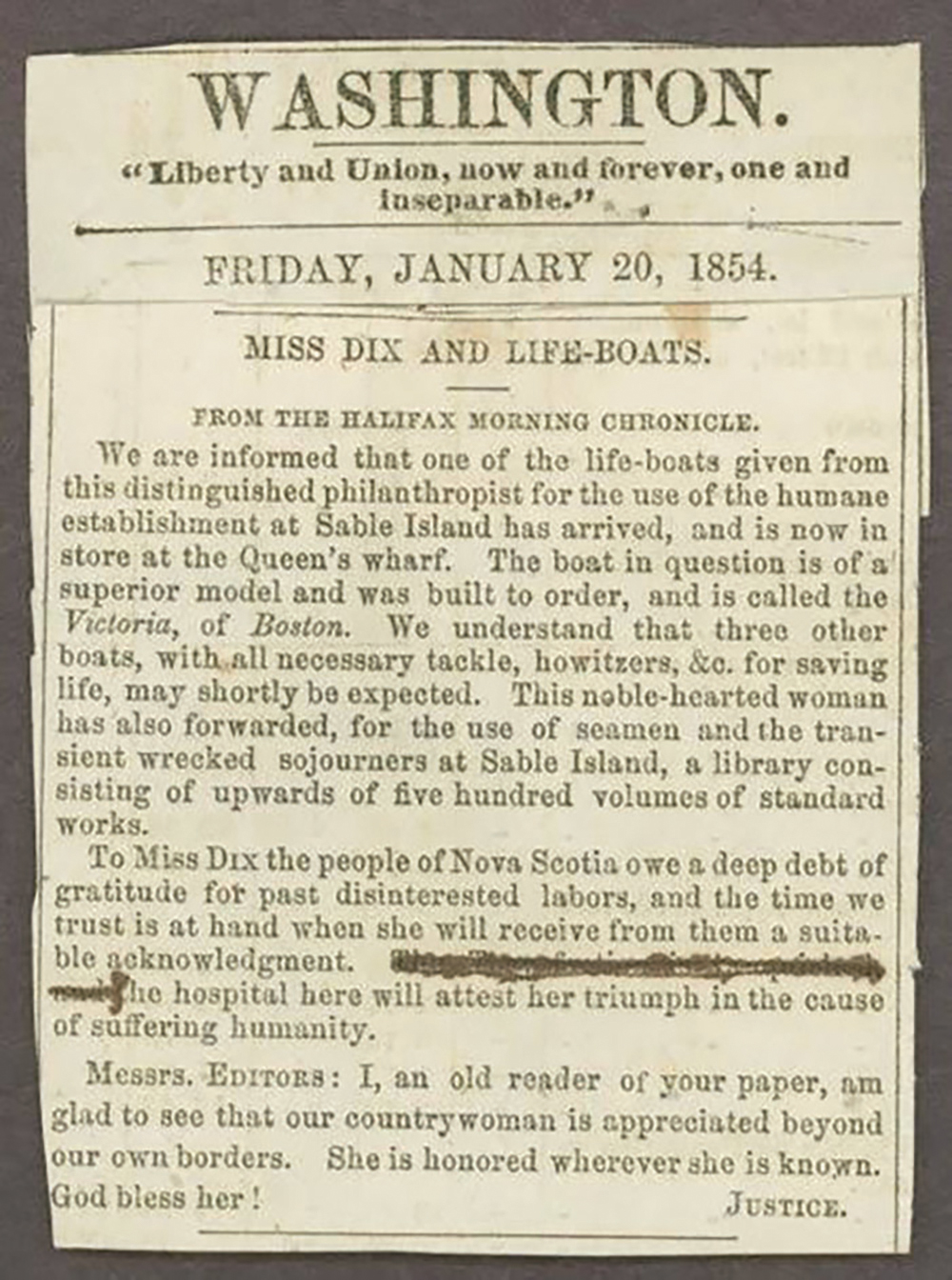

Dix did not stop at the borders of the United States. In the summers of the 1850s, she visited Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and St. John’s Island. By chance, she participated in the rescue of a sinking ship in Nova Scotia. Afterward, she campaigned for more life-saving equipment. Eventually, $60,000 was appropriated by Nova Scotia and Dix added money of her own—and her friends in Nova Scotia reported the new items were instrumental in saving an American ship the day after they arrived.

Dix went to Washington, D.C. in early 1849. The Mexican-American War had gained the United States vast territories, most of which were declared federal lands. General Zachary Taylor, hero of the Mexican-American War, had just been elected president. Dix intended to persuade the new administration to grant five million acres of federal land for “The Benefit of the Indigent Insane.”

In the whirl of parties and pre-inauguration festivities, she made the acquaintance of the incoming vice president, Millard Fillmore. The two were to carry on a sometimes passionate correspondence until Fillmore’s death in 1874.

Taylor died in July 1850. Dix’s new friend was now president. Passage of her bill seemed assured.

She stayed in Washington quietly building support, but the bill failed. Undaunted, she returned to Washington when the new Congress convened. This time she asked for 12 million acres of federal land. Support increased, but Congress adjourned without taking up the bill. Fillmore’s term would be over when Congress convened again. Ominously, one of the bill’s strongest opponents, Senator Franklin Pierce of New Hampshire, was elected President.

Persistent, Dix came back to Congress a third time, increasing her request to 12 million acres and $100,000 for “The Benefit of the Indigent Insane.” This time, the bill passed easily.

But success was short lived. While proclaiming sympathy for her cause, President Pierce vetoed the bill. In a 6,450-word message to Congress, Pierce argued social welfare was the states’ responsibility, not the federal government’s. Furthermore, Pierce argued, allowing this bill would simply encourage other social groups to petition for federal money and land.

Heartbroken, Dix left America for England. She planned to stay with her friends the Rathbones again, to relax and recover. She was no longer a young woman looking for an accepting family now. She was in her early 50s with a record of successes behind her. She couldn’t stay still. Hearing of deplorable conditions in hospitals in Scotland, she set out to investigate. As in America, she visited every place she could, recording what she saw. Returning to Liverpool, she sent memorials of her findings to influential members of parliament. The result was construction of two new Scottish hospitals to be operated according to her recommendations.

By 1858, she was back in the U.S., crusading for the poor and those with mental illness and intellectual or developmental disabilities. By now, she was one of the most-widely known and admired women in America. She had so many friends across the country, she seldom had to book a hotel. Where she could not change a system, she raised money to send books and clothes to prisons and poorhouses. She lived on very little.

A story is told that she was riding in a buggy in rural Michigan when it was held up. She confronted the robber, offering her purse if he would leave others alone. The robber recognized her, declaring she had been kind to him years before when he was in jail. He declined to take her money. Forcing it on him, she made him promise he would forego robbing some other “honest man or woman,” in exchange.

According to her biographies, in early 1861, while visiting Maryland, Dix overheard men planning to cut railroad and telegraph lines, march on Washington with a private militia and declare themselves de facto rulers of the United States before Lincoln’s inauguration. Lincoln himself was to be kidnapped and killed. Dix was friends with Samuel Felton, president of the Philadelphia and Baltimore Railroad, responsible for bringing Lincoln to Washington. Hastily, she went to Felton, telling him what she had heard. With that warning, Felton alerted Allen Pinkerton and Lincoln was saved and reached Washington.

“Why then,” Felton asked, “don’t you reveal this? All the world knows this story and believes it was Mr. Pinkerton who learned of the plot and foiled it!” Dix replied it would be immodest of a woman to claim such a thing.

Dix’s reputation was so great that at the outbreak of the Civil War, she was appointed Superintendent of U.S. Army Women Nurses. For the next four years, she trained nurses to her high standards and forced Army doctors to allow her nurses into their hospitals. She refused pay and gave herself no furloughs.

Worried her nurses would be sexually harassed by Army doctors, she wished to recruit only “women between the ages of 35 and 50 and of plain appearance.” Her nurses were to dress “without jewelry and wear plain dresses of black, gray or brown with no hoops.” She was strict. One of her nurses, Louisa May Alcott, called her ‘Dragon Dix’ in a letter home. (Many Army doctors called her much worse.) In mid-1863, some of her authority was taken away from her. She resigned her post in June 1865 and immediately returned to raising money for hospitals.

By 1881, her respiratory problems returned, and she was exhausted. No longer able to travel, she retired to the suite of rooms built years before in a New Jersey Asylum for her use. From there, she continued advocating for the disadvantaged through her letter writing, which hardly slowed down. In 1887, age 85, Dorothea Lynde Dix passed away.

In her lifetime, Dix held as many backward and puzzling views as she did forward-thinking ones. For example, while advocating decent treatment of those in need, she believed mental illness only affected white people. The brains of Black poeple, she wrote, were not sufficiently developed to become disordered. Why she would believe this in the face of her own evidence is a mystery.

Privately, she was a woman full of passions, raised in an era and household which suppressed them. As hinted at in her reaction to the “carefree” slaves, she believed morality was essential, but that it made people unhappy. She wrote and read poetry “to live,” she once said. Once, asked if she felt she was an example to young women, she vigorously denied it, hoping instead they “would not be so unfortunate as she” and instead, be happy becoming dutiful daughters, good wives, mothers and housekeepers.

Starting in the late 1960s, Dix’s legacy began crumbling. Buildings erected in the 1800s were oudated and hard to keep up. Dix desired to separate people with mental illness and developmental and intellectual disabilities from what she perceived as an unfriendly public, but practice turned toward integrating them into communities. Many of the 32 hospitals Dix founded or helped establish were closed, including Raleigh’s hospital.

But what remains of Dix’ legacy is twofold: to treat people with mental illness and developmental and intellectual disabilities with kindness and support, and to stop identifying their actions as criminal behavior. Dix’s empathy, meticulous reporting and dogged advocacy started a tidal, societal shift.