This former school counselor explores her creative voice at Artspace, making multimedia pieces full of color, pattern and personality.

by Colony Little | photography by Joshua Steadman

Jennifer Clifton’s colorful studio in Artspace is filled with paintings, custom-printed tea towels and a collection of vintage Robinson Ransbottom “Oscar” cookie jars. The unique ceramic crockery is shaped like the head of a World War I Doughboy, with comically large eyes and a lid fashioned into a brodie helmet. Clifton began collecting these jars in the years leading to her retirement and now has 72 of them. “I heard that Andy Warhol and Peter Max collected cookie jars, and I kind of became obsessed with the idea,” she says. The cookie jars are filled with nostalgic tokens like crayons, finger puppets, wax teeth and cigarettes— clues to the personality behind her vibrant, maximalist work.

The anthropomorphic subjects in Clifton’s paintings easily fit into this world of whimsy. In one, a toad wearing blue pants and a smart red ribbon around its neck holds a cane and a top hat, posed in a vaudevillian stance in front of a chorus line of pink flamingos. In another, a carnival showgirl in a Grecian one-shoulder gown shows off hyper-toned muscles, a flex of strength that’s offset by a delicate pink ostrich feather headdress on her head. Clifton’s art is infused with charm, nostalgia and a tinge of rebellion, which makes her work attractive in galleries (she recently wrapped a solo show at Rebus Works) and restaurants (you can find her work on the walls at Irregardless).

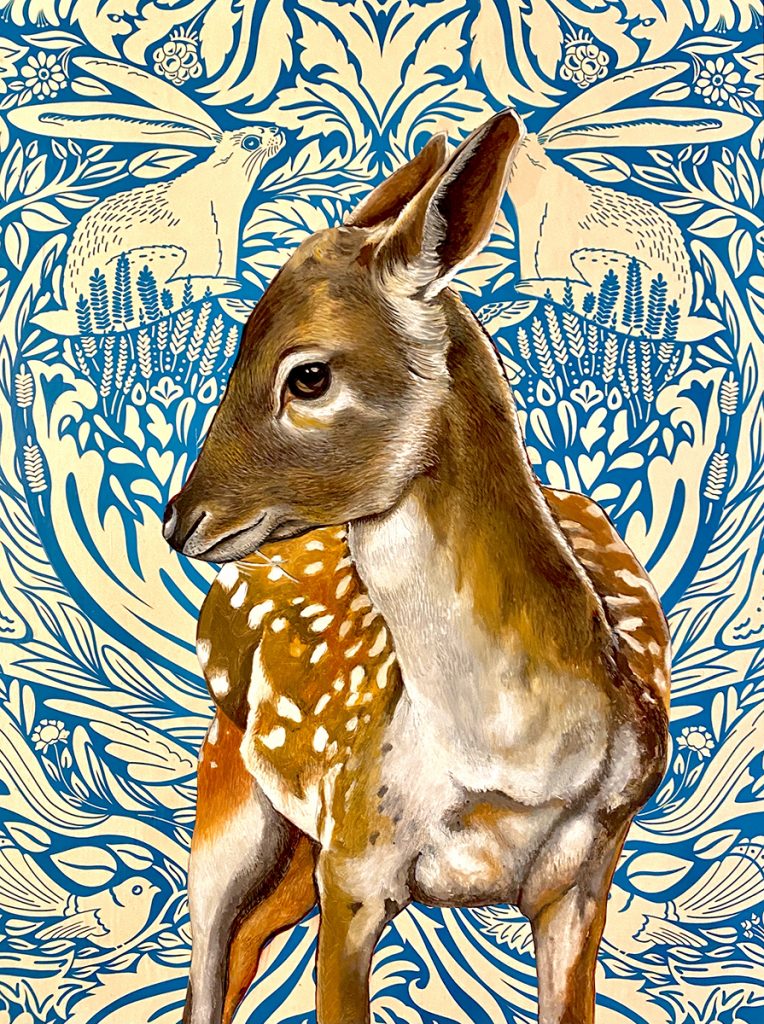

Dave Wofford of Horse & Buggy Press in Durham featured Clifton’s work in a group show called Smothered and Covered in 2022. “I’ve been a big fan of Jennifer’s playful and adventurous work for a number of years,” he says, noting that his favorite works include achromatic pencil drawings of circus performers paired with vintage wallpaper patterns. “It’s great, unique work.” Clifton was born in Texas, then lived in Connecticut before her family moved to Louisiana. She spent her formative years there in a river town named Slidell. It was a difficult transition for Clifton, who was bullied mercilessly for her first year in her new hometown.

But in art, Clifton found joy and solace, something that she attributes to her mother. She’d work with her mother on craft projects, especially during the holidays. Her mother also brought her creativity into the elementary school, where there was no art teacher on staff. “She volunteered and had a cart where she went from class to class,” says Clifton. “Seeing my mom understand how important that was to me subliminally got into my brain.” Clifton went on to study art history at Florida State University, with a minor in studio art. She particularly loved lithography. “It was my favorite part of the day — I took as many printmaking classes as I could,” she says.

“I found my people at the print lab at night at Florida State.” After graduation, she relocated to New Orleans, where she briefly worked in a gallery (she found she hated being market-facing), then began teaching art in elementary schools. She moved to North Carolina to pursue a master’s degree in counselor education at North Carolina State University, and she, along with her husband and two children, have called the state home ever since.

Here, she worked as an elementary school counselor for 20 years, a job inspired partly by her childhood experience with bullying. “It was such a torturous experience, but it made me more empa- thetic,” she says. “I was good at helping kids feel encouraged and supported and helping them find their own strengths and resilience.” During this time, Clifton’s artistic pursuits fell mainly into crafting with her two kids, instilling the same love for creativity that her mom cultivated in her as a young girl.

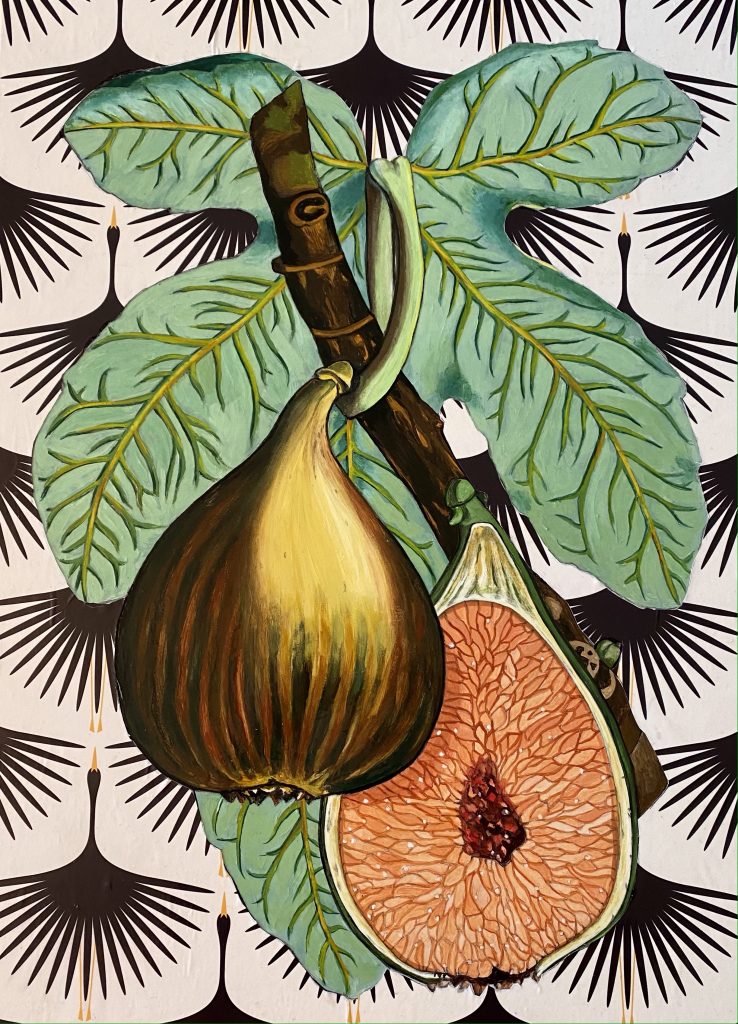

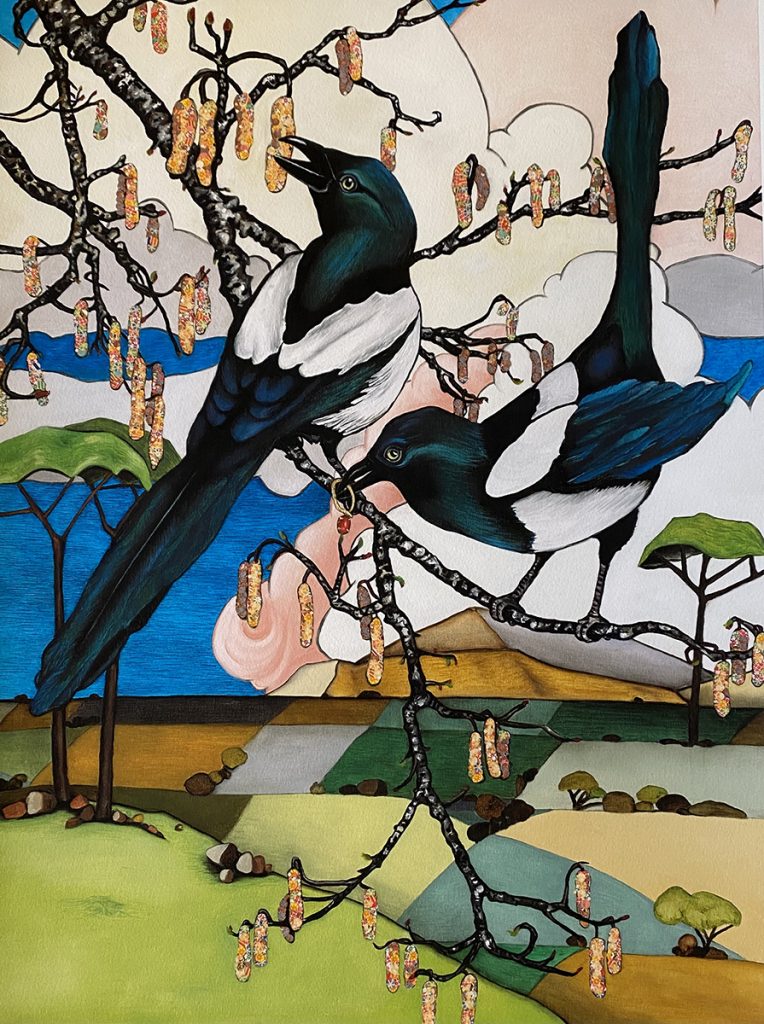

Clifton retired in 2018, and with her children grown, she found a surplus of energy that needed a new home. She began to rekindle her love for art, combining oil paint, gouache (a form of watercolor) or charcoal with vintage wallpaper motifs. Since then, she’s cre- ated an extensive body of work steeped in nostalgia for Victorian-era botanicals, animals and vintage-style portraits. “A lot of what came out during this process were anthropomorphic animals and whimsical things, because I wanted to focus on joy and strength,” she says.

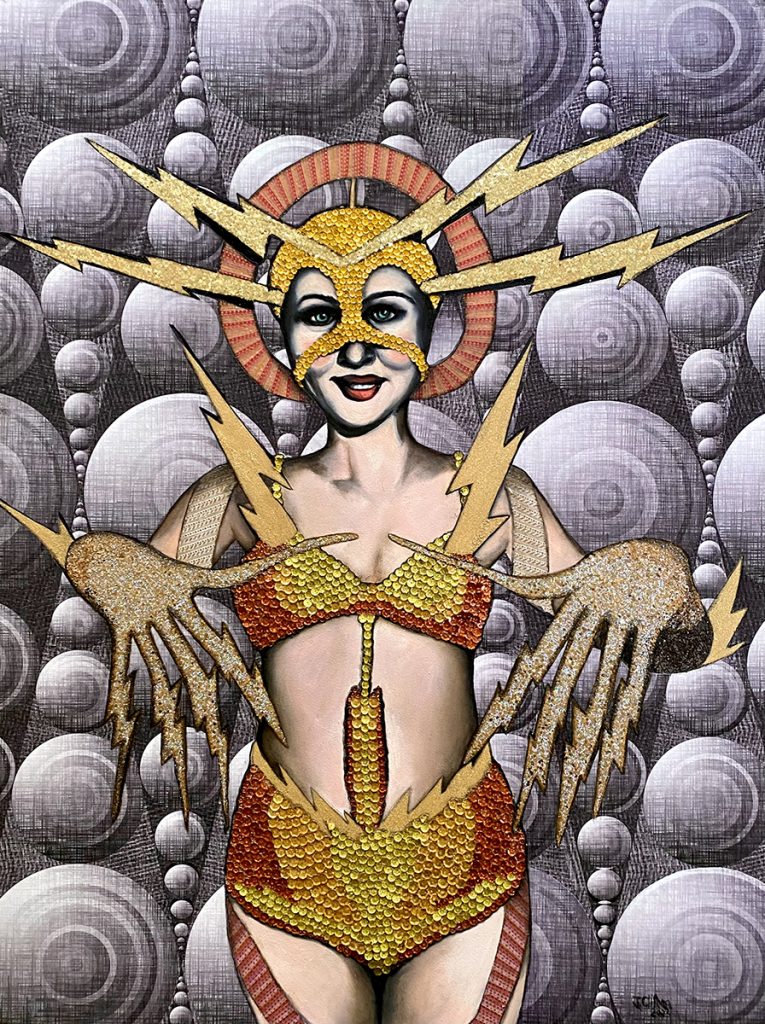

Many of her portrait subjects are women, particularly carnival performers and pin-up girls. “I was really interested in vaudeville and turn-of-the-century circus girls — I was in the circus at Florida State,” she says, as casually as if it were an average rite of passage. (Turns out, she earned P.E. credits by performing bike routines and learning how to juggle.) While her subjects are often whimsi- cal, her process is methodical. Clifton starts with a sourced image that she paints over in either oil paint or gouache; her characters are then embellished with painstakingly placed glitter and sequins.

As a final step, she’ll place wallpaper over the subject and exactingly trace around it to reveal the subject underneath. “A lot of people ask why I don’t paint on top, but you really can’t paint on top of wallpaper because of its texture; it just doesn’t adhere,” she says. “But I think embedding the subjects within the wallpaper really makes it pop.”

Clifton’s work is often humorous, and it often includes autobiographical notes: the glitter and sequins recall the intricately beaded costumes worn by carnival revelers and performers in New Orleans, for example. While she’s very careful about not dictating interpretations of her work, she uses small details to lead viewers down a path of inquiry and discovery.

Through her portraits of female performers, Clifton restores their agency, turning them from exotic objects of beauty and spectacle into symbols of ferocity and power. “I find a lot of strength in these women who had to do ridiculous things for money,” she says, pointing to a black-and- white portrait of a turn-of-the-century snake charmer that she has surrounded with a vibrant green Pucci-inspired pattern from the 1960s.

Another portrait was inspired by a 1939 image of Elmira Humphreys wearing a bedazzled bikini, large headdress, and oversized gloves with fingers shaped like lightning bolts. “Women dressed up for trade shows, like Miss Radio Queen, who was a model for electricity,” says Clifton. “I want my work to have a voice and theme around ‘strength is beauty, and beauty is strength.’ I’m looking back in time to find examples of that.”

Other interpretations are more cheeky. In the portrait of Sir Walter Raleigh she made for WALTER, for example, the cigarette in his cap and candy necklace (with the letter “E” for Queen Elizabeth) hint to some of the infamous elements of the explorer’s life. Clifton is now exploring ways in which she can extend the viewer’s gaze into concepts and themes that aren’t as fanciful as her animal and botanical works might suggest. “I have a joyful side, but I have a dark side too,” she says.

Work from her latest series, Dazzling Ugly, is confrontation with discomfort. One work in progress features a ferocious, sequined lion, poised to strike. In one corner of the canvas an elephant’s leg is just visible, hinting to an earlier casualty; in another corner of the canvas, a dog is lunging toward the feline aggressor. These works represent a demarcation between how she presented herself professionally for decades and how she’s seen artistically. “In my work as a counselor, I often had to be the cheerleader for staff and students, and that can be exhausting,” she says. “As an artist, I can be a more complex, genuine person.”

This article originally appeared in the January 2025 issue of WALTER magazine.