A look back at the origins and evolution of this annual celebration of agriculture and innovation, which was first held in Raleigh in 1853.

by Joel Haas | photography by Justin Kase Conder

Under a crisp blue sky, the smell of deep-fried treats wafts over an enthusiastic crowd, the dings of games and whirs of rides mingling with a banjo strumming folk music.

Inside, the smells are decidedly earthier and the pleasures subtler: the myriad colors and shapes of the feathers on prize poultry, the rich coats of muscled cattle rounding an arena, the quiet expectation on faces gathered around an incubator, waiting for a chick to peck its way out of an egg.

Since 1853, the North Carolina State Fair has shifted sites three times. It’s been suspended during wartime and for periods of tight budgets, it’s been delayed by a hurricane and canceled by a pandemic. But it remains a fall fixture in North Carolina, and here in Raleigh, we claim it as our own.

A Showcase for Farmers

The fair’s origins stem from The Great Exhibition of 1851 in London. This European fair offered a forum for innovators in everything from agriculture to artillery to show what they did and how they did it — historically, these sorts of fairs had been more of an opportunity for farmers and craftsmen to gather to sell their wares. For the first time, the fair became a place to instruct the public at large, and to support and create innovation.

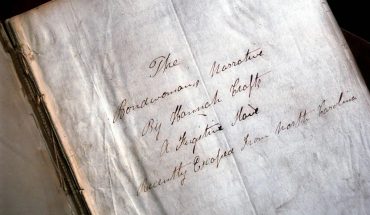

In North Carolina at the time, nearly 90% of our residents worked in some aspect of agriculture. But many farmers were illiterate, as well as isolated by few roads and slow communication, so information was often passed along by word of mouth and tradition.

The North Carolina Agricultural Society formed in 1852 with the purpose of raising funds for a fair to share practices. By 1853, they’d chosen a plot to hold it, 16 acres east of the then 1-square-mile town of Raleigh.

Notices were sent to all the newspapers in the state encouraging farmers to bring items to show and asking them to stay and talk about them. As exhibitors reached the fairgrounds, they shared their names and what they would demonstrate.

The Raleigh & Gaston Railroad was so enthusiastic about the fair that it offered round-trip tickets for half price and brought exhibits to the fair for free. The fair ran horse races for entertainment.

And people came! On one of its six days, over 4,000 people visited the fair — a huge success by the standards of the day. The Agricultural Society erected more wooden buildings, along with sheds and tents, for the 1854 fair.

Steady Growth

The fair grew in size and success through 1859. In 1860, it was canceled as the state entered the Civil War, and it didn’t restart until 1869, after the early years of Reconstruction. By then, the buildings were in poor shape and the tents were gone.

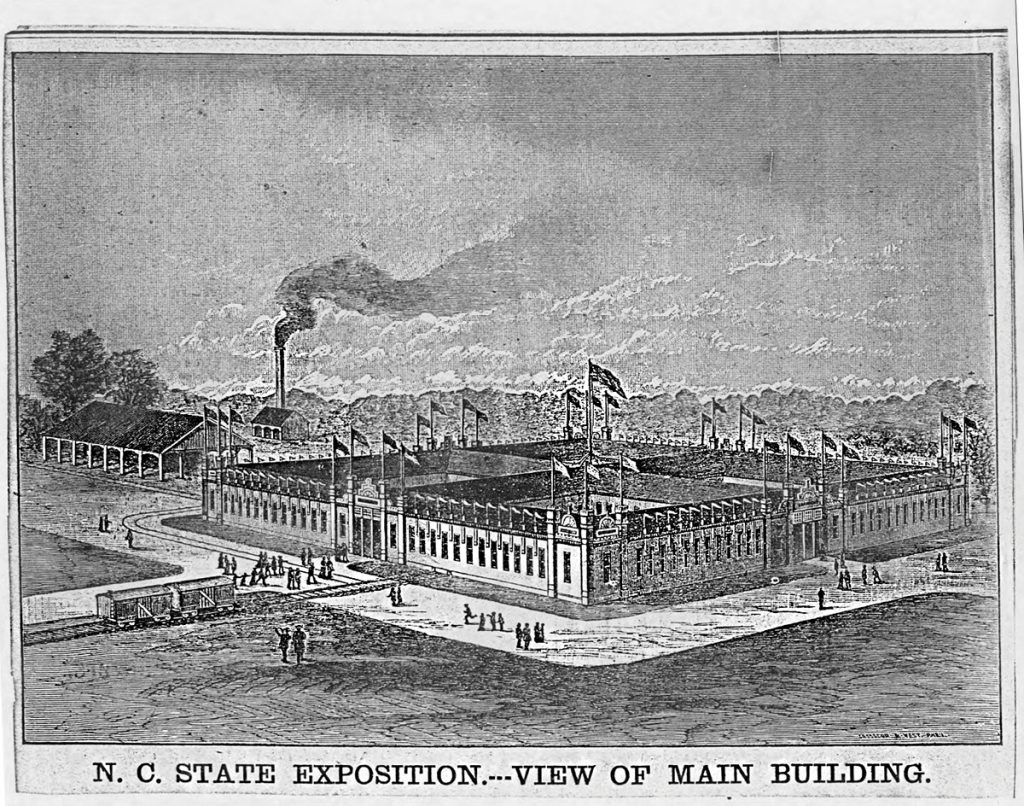

So in 1873, the fair moved to a new, larger area on Hillsborough Street across from North Carolina State University’s current location. It’s now home to the Raleigh Little Theatre, and the former horse race track outlines its rose garden.

In 1926, the longtime sponsor and founder of the fair, the NC Agriculture Society, was too broke to continue. The NC Department of Agriculture took over responsibility, donating 200 acres at the corner of Blue Ridge Road and Hillsborough Street for a new site.

Here, two large brick exhibit halls connected by an arched gate were completed in time for the 1928 fair. They still stand today as one of the entry gates.

Mired in the Great Depression in 1933, the state contracted George Hamid, an entrepreneur, to run the fair, but by 1937 it was back in the hands of the NC Department of Agriculture, where it has remained since.

The fair was suspended during WWII, from 1942-1946, and then in 2020 for the Covid-19 pandemic, but has remained in its same location for nearly a century. In 1965, Black and white 4-H groups competed together for the first time.

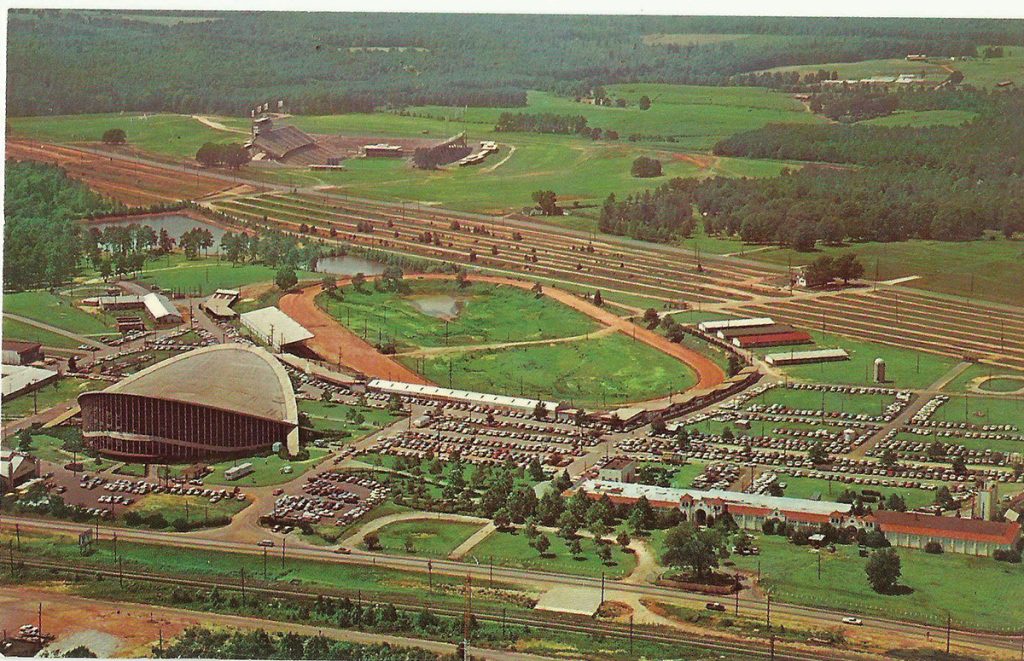

And in 1978 the fairgrounds acquired an additional 144 acres of land, bringing the total to 344 acres.

Over time, the length of the fair has expanded, to 10 days in 1986 and to its current 11 days in 2008. The number of buildings has expanded, too, including the addition of the N. C. State Fair Livestock Pavilion (now known as J.S. Dorton Arena) in 1951 — then boasting the world’s first column-free roof — and the Exposition Center in 2005.

Innovations & Entertainment

As the fair continued to grow, so did the scope of what it showcased. In 1878, a telegraph employee hooked a wire from the grandstand to an office building, allowing attendees to talk to each other using the newfangled telephone.

Six years later, electricity was first used to light the fair. In 1894, there was a photography exhibit; in 1895, chicken incubators were a main attraction.

The first telecast from a new educational television station, WUNC-TV, was broadcast from the N. C. State Fair in 1954. In 1958, staff from NC State operated an atomic reactor during the fair, alongside an exhibit of nuclear science.

Topical science exhibits continued: in 1972, the fair sponsored the world’s largest space-related education exhibit, which included the Apollo 12 command module; there was a 1995 exhibit on CyberSpace, about information technology; 2001 brought an exhibit on biotechnology; and 2008 focused on environmental science. (That same year, the fair started its first social media accounts.)

Horse races and buggy races were the initial entertainment at fairs. In 1901, there was even an ostrich race (though it is unclear how many North Carolinians were raising racing ostriches).

In 1910, auto racing was introduced; that same year an early barnstormer aircraft landed, using a New Bern Avenue golf course as a makeshift landing strip.

In 1918, the fairgrounds were used by the Army as training grounds for another newfangled invention, the tank. In 1955 the World’s Championship Rodeo did nightly shows with more than 100 bulls and bucking broncos.

In the early 1930s, the first carnival-style acts marked the start of our modern midway. By 1939, the midway had grown to a mile long, with 50 rides. In 1949, Ferris wheels, merry-go-rounds and dare-devil motorcyclists were featured.

In 1964, the nightly fireworks were introduced — alongside a 14-foot tall mailbox from the Post Office, where visitors could send out postcards from the fair.

By the mid-2000s, more than 100 rides could be found on the newly expanded midway. In 2019, the largest traveling Ferris wheel in North America, the SkyGazer, treated guests to views of Raleigh from 155 feet in the air.

In addition, politicians and other noteworthy figures have entertained the crowds. Along with state legislators, five U.S. presidents have visited the fair: Teddy Roosevelt in 1905, Harry Truman in 1948, Gerald Ford in 1976, George H.W. Bush in 1992 and Bill Clinton in 1996.

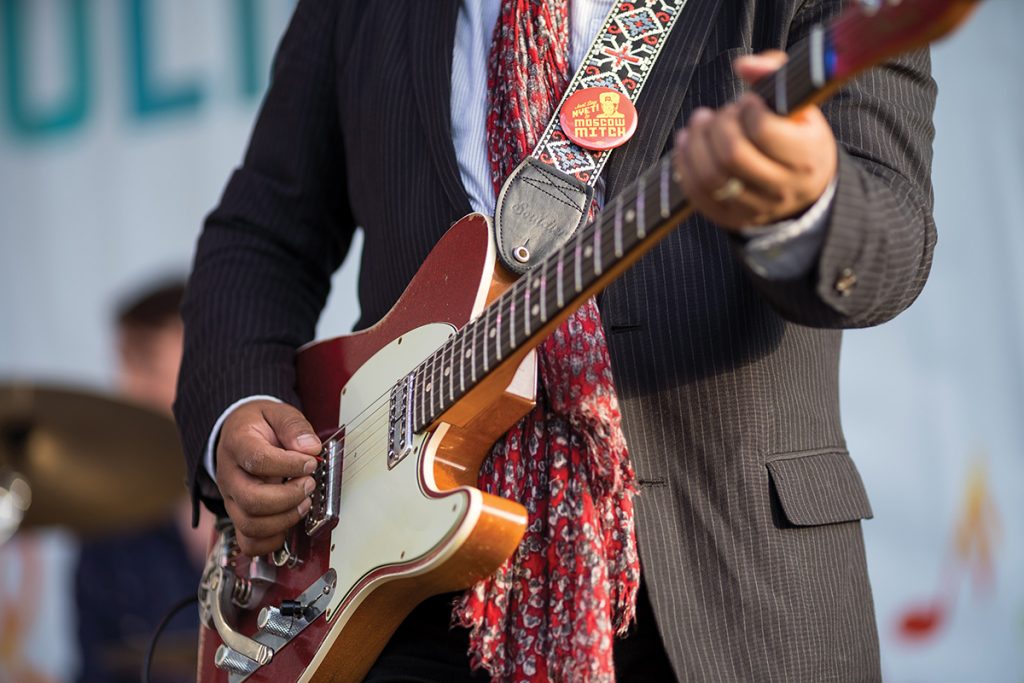

But today, you’re more likely to find a musical act than a politician on stage.

The first Folk Festival was held in 1948 to showcase traditional North Carolina music and dance. By 2015, the Homegrown Music Fest brought more than 75 North Carolina musical acts across three stages.

The fair’s food has also become a form of entertainment in itself. In the early days, farmers brought preserves, cakes and pies to be judged. The first food booths on the fairgrounds were in 1900, run as fundraisers by churches and civic groups.

The first concessions at the fair were ham biscuits, sold by the Cary United Methodist Church in 1916. Foot-long hot dogs were introduced in the 1950s, and in 1978 the NC State Food Science Club served its first ice cream cone.

This year there will be a wide range of food, including once-a-year rarities such as deep-fried candy bars, cookies, ice cream and butter. As North Carolina has grown more diverse, so have the offerings, with international fare alongside Southern classics.

Honoring Agriculture

While the food and entertainment are certainly part of the appeal, the fair is still true to its origins: a celebration of farming in our state.

Agricultural exhibitions such as livestock judging, home economics and horticulture, and other farm related divisions remain under the state’s control. There are pig races, draft horse pulls and tractor pulls.

Kids can visit the petting zoo and then go visit the animals entered to compete for prizes. Newer features include the NC Public House, showcasing local beer, wine, cider and craft sodas, as well as a kids’ decorating competition.

In 2022, the fair received more than 36,000 applications for entry to its various competition categories.

This year, the fair will sprawl over 344 acres with an expected attendance of about 1 million. But should you want to go back to those 1850s origins, you can always visit the Village of Yesteryear, which first opened in 1950.

There, you can take in heritage crafts like blacksmithing, basketry, pottery and spinning thread by hand — and marvel at how far we’ve come.

This article originally appeared in the October 2023 issue of WALTER magazine.