William and Mary Joslin nurtured their 4-acre garden for decades, then donated the land to the City of Raleigh to be used as a park.

by Helen Yoest | photography by Liz Condo

The freshness of spring brings awareness of new life; sleeping flora and fauna awaken our senses. Indeed, in the Joslin Garden, newness abounds. Visitors first notice the colorful camellias in bloom, then the garden’s quietness — you can hear the birds chirping, singing and preening as mating season begins again. The ferns emerge, forming fiddleheads that will soon unroll into leafy blades, and the moss is forever a verdant green.

If you look closely, spring ephemerals abound: blooming trillium, galanthus and cyclamen. Between Anderson Drive and St. Marys Street, this city park offers more than 4 acres to explore, a refuge for personal renewal. As a young couple in the 1950s, William and Mary Joslin wanted to do their part to steward the land. Together, they built this garden to conserve its beauty for the future.

William Joslin

Born in 1920 in the neighborhood formerly known as Cameron Park, William Joslin played in the surrounding creeks and woods. The impact was deep and lasting. William became a birder and hiker and loved everything about nature. After graduating from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, William had just turned 21 and was finishing his first semester at Columbia University Law School in New York when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor and the United States entered World War II. He enlisted in the Navy, where he served as a lieutenant on the U.S.S. Massey, a destroyer in the Pacific.

By the time the war was over and William finished law school, the 158-acre forest in the Raleigh of his youth was being developed as the Southeast’s first shopping center. Cameron Village, now known as The Village District, opened in 1949.

These were new times. Along with single-family residential areas and apartments, the shopping center reflected postwar economic and demographic changes, serving car-oriented residents building their postwar lives.

At the time, land conservation was not widely practiced in Raleigh and Wake County.

As a young man, William saw the many advantages of growth, but also saw that it would be necessary to plan in order to save special places.

Mary Coker Joslin

Mary Coker was born in Hartsville, South Carolina, in 1922, and came from a scientific, agricultural family that valued education. Mary’s grandfather, James Lide Coker, founded Sonoco Products Company, now an international corporation, as well as Coker College in Hartsville. Mary’s father, David R. Coker, was a plant breeder who founded Coker’s Pedigreed Seed Company. In the early 20th century, the company developed and marketed varieties of cotton with fiber of exceptional quality, later expanding to include corn, oats and sorghum.

Mary’s mother, May Roper Coker, was an avid gardener. In the early 1930s, her brother-in-law, William C. Coker, a professor of botany at UNC, gave her 35 acres of land just outside of Hartsville. There, along the bluffs of Black Creek, there were large stands of Kalmia Latifolia, the native mountain laurel. Over the next four decades, she developed the garden now known as Kalmia Gardens. At her death, this garden became part of Coker College (now Coker University).

Mary attended Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York, where she studied botany. During her summers she returned to Hartsville to work at the Coker’s Pedigreed Seed Company, and her work eventually led to the development of a soybean variety named for her (the Majos), which is the ancestor of a bean that is widely planted and marketed today.

Early Days Together

One of Mary’s cousins, Thomas Rogers, was a good friend of William Joslin’s during their undergraduate years at Chapel Hill. On a visit to New York, Tom introduced William, then a naval officer, to Mary, who had come down from Vassar into the city. During the war they corresponded, and in 1946, they married in Hartsville. Their wedding reception was held at Kalmia Gardens.

After William finished law school, he clerked for U.S. Supreme Court Justice Hugo L. Black in the 1947-1948 term. Then the couple moved to Raleigh, where William opened his law practice. In 1950, when Mary was 27 and William 29, they set about finding some land where they could put their heart and soul into developing a garden, and where they could raise their family.

The Joslins found a little over 4 acres for sale off of White Oak Road — then on the northern outskirts of Raleigh — along a tributary of Crabtree Creek. The land had once been part of Arrowhead Farm, owned in a previous generation by J. Bryan Grimes, who had been the N.C. Secretary of State during the first two decades of the 20th Century. (The farm’s name came from the many Native American arrowheads that have been found on the property over the years.)

They both loved the rolling terrain of the land and the little stream that ran through it; they loved large hardwood trees and the pine forest that had grown during the years after farming operations ceased. The soil was the good old red clay of the North Carolina Piedmont region.

Working the Land

Over their 60 years as stewards of their land, Mary and William built bridges over the stream, planted many rare and native plants, grew all types of vegetables and fruits, and created perennial beds, a formal garden, a scuppernong arbor and several areas devoted to North Carolina native wildflowers. In the 1960s, they maintained a clay tennis court. And for about 10 years William kept bees and harvested the honey. From his scuppernongs he made wine.

William became active in the North Carolina Chapter of the Nature Conservancy with its inception in 1977, and in the 1980s he also became involved with the Triangle Land Conservancy. As they grew older, William and Mary began thinking about the best way to preserve their land for the enjoyment of future generations, and in 1997 they granted a conservation easement on the property to the Triangle Land Conservancy.

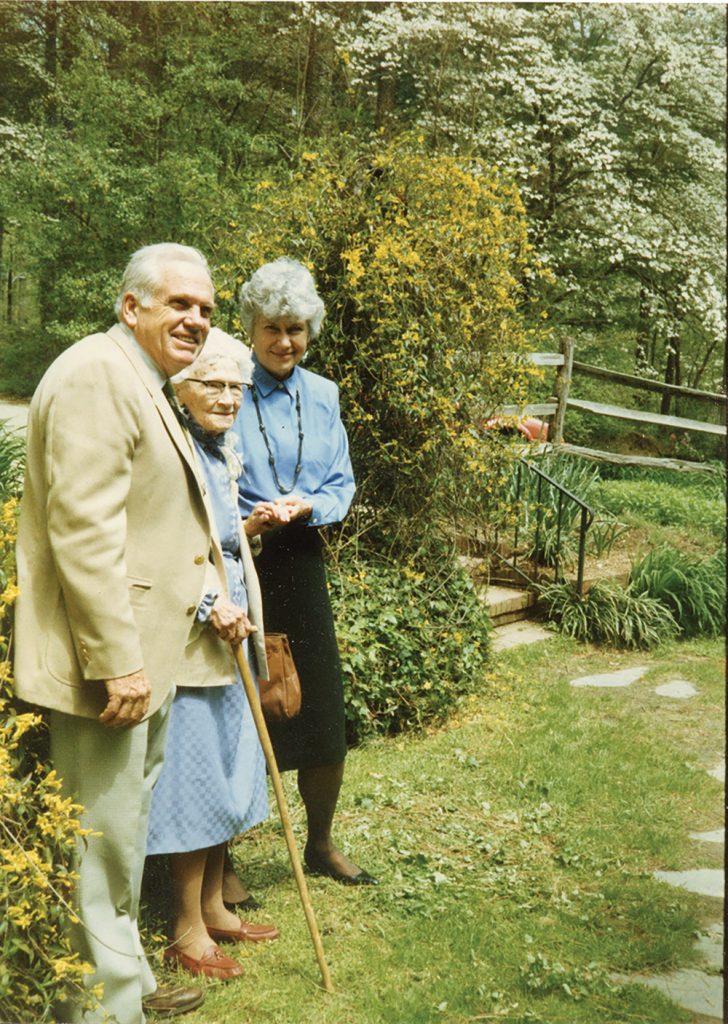

In 2010, the Joslins approached the City of Raleigh about a donation of their home and garden for a park. They worked with then-mayor Charles Meeker to create the City of Oaks Foundation, a nonprofit organization whose purpose is to support the Raleigh parks system. After William’s death in 2011, Mary continued to live in the home and maintain the garden. At her death in 2016, the foundation maintained the property until the infrastructure was in place for the city to accept it. On Earth Day, April 22, 2021, the Joslin Garden became a City of Raleigh Park.

The Joslins hoped to make the garden accessible to all, and now it is — open from sunrise to sunset. Today, visitors are charmed by the escape from the hustle of city life, walking their dogs, sitting to reflect, or walking the trails. The hilly terrain holds echoes of its previous lives, like gentle terracing from its highest points down to the creek from its days as farmland and a garden area called the Jeu de Paume, which used to be the old clay tennis court.

Wildflowers, pollinator plants and nectar- and pollen-rich plants — many descendents of the diverse plantings of the Joslins — provide food for bees, birds and butterflies. “The Joslin Garden brings nature and peace closer to us all in our busy city,” says Meeker. “It’s always a great joy to visit.”

This article originally appeared in the March 2024 issue of WALTER magazine.