This Oberlin Road estate holds an untold piece of Raleigh’s Black history still being uncovered by fifth-generation owner Cheryl Crooms Williams.

by Courtney Napier | photography by Catherine Nguyen

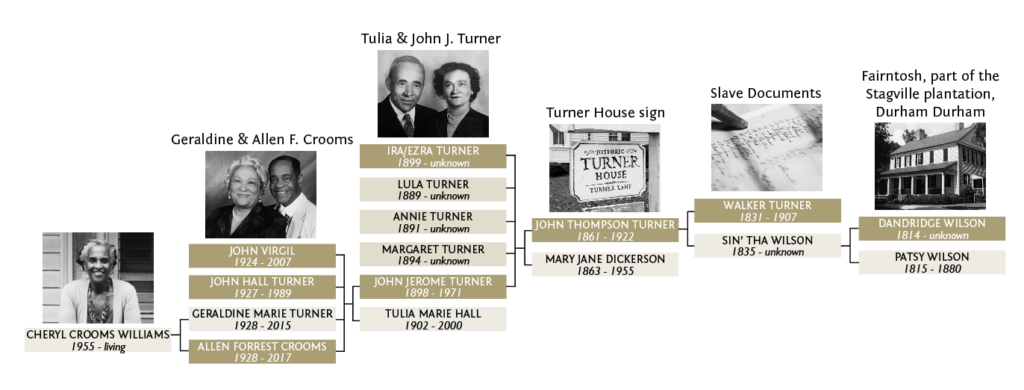

In 2001, Cheryl Crooms Williams’ daughter, Brooke, then in the fourth grade, came home from school in Los Angeles County with a project. “She was tasked with creating her family tree,” Cheryl says. Having inherited a passion for American history from her own mother — a high-school educator — Cheryl was excited about the prospect of learning more about her heritage.

So Cheryl and Brooke spent countless hours on the phone with family members living in North Carolina and New Jersey, listening to their stories. The oral histories they collected for Brooke’s project stretched back generations, but there were gaps.

And those gaps became the inspiration for Cheryl to start a vast genealogical exploration of her own, one that would fill the next two decades — and is still ongoing.

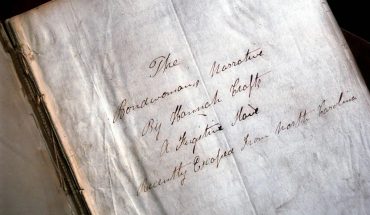

For many Black families in the United States, researching one’s family tree produces more questions than answers. Records become sparse once you cross into the 19th century and earlier, when Black people were seen by much of the South as either property or refugees.

According to the “Records of Enslaved People” page of the State Library of North Carolina website, “Slaves were enumerated on all federal census records from 1790 to 1860, but not by name.”

That means family historians and genealogists must acquire the 1870 census, the first to list all persons by name, then cross-reference it with “the 1860 and 1850 slave schedules that list, under the name of the owner, each slave only by sex, specific age and color.” It’s an inexact process that makes finding ancestors exceedingly difficult.

While all slaveholders had to list their human property by name in the census starting in 1870, families with large amounts of enslaved Africans and African Americans started the practice much earlier.

The Cameron family, the largest plantation owners in North Carolina, used each enslaved person’s full name (as given by the slaveholders) in their records. Cheryl knew her family had lived in the Raleigh area for many generations, so she started going through these records and connecting the dots. This provided her family with something most Black families will never see: the birth papers and the bills of sale of their ancestors. For Cheryl, it was a gut punch.

“I had always assumed that this was my heritage, but holding this piece of paper was an emotional experience,” she says. She’d found this connection to her ancestors, but it was stark evidence of the reality that they’d faced as enslaved African Americans.

Cheryl learned that Sin’ Tha (sometimes referred to as Cynthia in official documents) was her great-great-grandmother, an enslaved laborer at Peaksville, part of the Stagville plantation. This plantation was one of a conglomerate of forced labor farms and family mansions owned by the Bennehan and Cameron families that spanned what is now Durham, Orange and Wake Counties.

The family was described by their contemporaries as having the largest land holdings east of the Mississippi River — a vast holding that by the 1860s included 30,000 acres of land, worked by nearly 1,000 enslaved Africans and African Americans, according to North Carolina Historic Sites.

Sin’ Tha’s life changed in 1865. The Civil War ended and those slaveholders resisting the Emancipation Proclamation of two years earlier were forced to free their enslaved Americans by Union soldiers. Sin’ Tha and her husband, Walker Turner, made their way from Orange County to a new settlement of free and recently freed Black families on the rural, western outskirts of Raleigh.

In the area that would eventually be known as Oberlin Village, they hoped to find opportunities to prosper and experience a sense of freedom. They also moved there to be near family, including their grown son, John Thompson Turner, and his wife, Mary.

Dr. M. Ruth Little, an art and architecture historian, has contributed greatly to the research and modern documentation of Historic Oberlin Village. Along with assisting in the applications for joining the list of National Registry of Historic Places, Dr. Little also wrote one of the most comprehensive research papers on the legacy of Oberlin, entitled “Rooted In Freedom: Raleigh, North Carolina’s Freedmen’s Village of Oberlin, an Antebellum Free Black Enclave,” published in The North Carolina Historical Review. She describes the significance of the community this way: [Oberlin] is no ordinary freedmen town but an antebellum free Black enclave that grew into an African American municipality, built away from White supervision…. Oberlin Village provided a legacy of freedom and land ownership, creating an enduring Black settlement with an elevated degree of home ownership, artisanal pride, and an irreproachable reputation.

John embodied a quality Cheryl refers to as “an entrepreneurial spirit that flows through my family line.” On Feb. 5, 1889, John, a grocery proprietor, purchased a one-story, three-room house on Oberlin Road for $500. By 1891, he owned $2,650 worth of real estate and $100 of personal property.

According to Dr. Little’s research, the Turner family was among the wealthiest families in Historic Oberlin Village, including “Reverend M. L. Latta [founder of Latta University] and Willis M. Graves [a brick mason and justice of the peace].”

John later opened the Raleigh Shoe Co. on Hargett Street. One of his partners was businessman and banker Berry O’Kelly of the Method neighborhood, a nearby freedmen’s settlement.

Ten years after first purchasing the home, as their wealth and status grew, John transformed his home by adding a two-story, Victorian-inspired I-House addition to the front. It created a grand sight for passersby on Oberlin Road: the facade features a polygonal bay, Tuscan porch columns and a two-story, pedimented portico.

Through the Turner House’s ornate double doors, a central staircase and short hallway are flanked by two parlors.

The home boasts fireplaces in every room, with the most elaborate mantels surrounding the shared fireplace between the north parlor and the dining room. The original, one-story section of the home in the rear opened up to a flat, shaded yard with brick-lined flower beds and magnificent oak trees.

John and Mary had five children: Lula, Annie, Margaret, John Jerome and Ira (also known as Ezra). As the eldest son, John Jerome inherited the Turner House after his parents passed away, and lived there with his wife, Tulia, and their three children, John Virgil, John Hall and Geraldine. John Jerome also took over the shoe store his father started, but the business did not make it through the Depression Era. Miraculously, the family retained ownership of the home on the small earnings of Tulia’s work as a seamstress.

After John Jerome passed away in 1971, John Virgil moved into the Turner House to care for the home and his aging mother. John Virgil had graduated from Raleigh’s segregated Washington High School in 1941, then enrolled in the North Carolina College for Negros, which is now North Carolina Central University.

He became a prominent alumni and educator at NCCU, serving as associate dean of the business school, then becoming the concierge for the chancellor.

In 1984, he was awarded North Carolina’s highest honor — the Order of the Long Leaf Pine — for his 35 years of service at NCCU. John Virgil worked at his alma mater another 15 years, getting the privilege of hosting dignitaries such as Guinean President Ahmend Sekou Touré, United States President Gerald R. Ford and South African Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu. (Today, there are multiple statues and references to eagles, the NCCU mascot, around the Turner House and its yard.)

Meanwhile, his sister Geraldine met her future husband, Allen Forest Crooms, as a student at Shaw University, from which they both graduated in 1950. After giving birth to their first child, Cheryl, at St. Agnes Hospital in 1955, they moved several places with the U.S. Air Force, then to Allen’s native New Jersey, where he continued his career as a dentist and Geraldine became a high-school teacher. Their brother John Hall attended North Carolina Central University, where he played baseball before starting a career in the military.

In 2001, Tulia Hall passed away and, like his father before him, John Virgil became the owner of the home on Oberlin Road. He soon began the process of preserving his family’s home by submitting an application for its inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places.

The John T. and Mary Turner House was listed in 2002, along with Oberlin’s Reverend M. L. Latta House, the Willis M. Graves House and the Reverend Plummer T. Hall House.

John Virgil passed away in 2007 after leaving a legacy as an educator and community leader, and starting the grand task of preserving the history of his family. Neither John Virgil nor John Hall had any children, so their sister Geraldine inherited the Turner House. In 2008, she and Allen, then in their late 70s, decided to move back to Raleigh and become the next stewards of her childhood home.

Geraldine and Allen soon called on their eldest daughter to assist them in caring for the home and each other. “I can’t tell you how surprised that ended up being me, because I was the defiant child,” Cheryl says. She had married and moved to California decades earlier, after graduate school.

Realizing it was the right next step for her, Cheryl retired from her career as a banking executive and moved to Raleigh in 2010. Her eldest, Bryce, had already made a life for himself in Los Angeles. Cheryl remarried in 2012, and her daughter Brooke made the move to Raleigh a few years later.

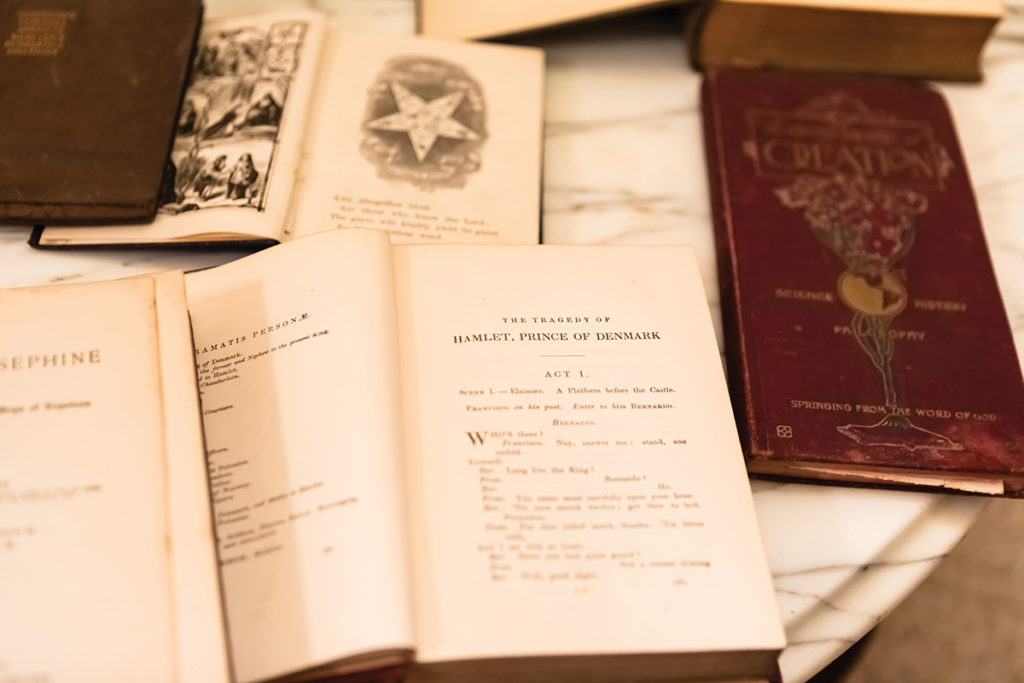

When Cheryl returned to the Oberlin Road house, she became the next generation in its 120 years of continuous family ownership. She found that it had aged beautifully on its exterior, but needed someone with the strength and interest to bring it back to its former glory. Inside, the home had become a treasure trove of family photographs, papers and fascinating antiques, particularly thanks to John Virgil’s interest in history and travel.

Paintings depicting Asia and Africa hung on the wall, striking brass and marble-like figurines were displayed on the ornate mantles and antique mahogany and cherry wood furniture filled the rooms. The photographs and historic documents she found fed her research and created new threads to pursue.

Shortly after moving to Raleigh, Cheryl met Sabrina Goode at the church their families attended for generations, Wilson Temple United Methodist Church. The women became fast friends, learning of their families’ connected history — Goode descended from one of its founding families, the Morgans. “During one of our many conversations,” Cheryl says.

“I learned of our fathers’ friendship during their military service in the U.S. Air Force.” They were also both deeply concerned about protecting their families’ legacies and that of Historic Oberlin Village.

The two women, along with a handful of other descendants and supporters, founded the Friends of Oberlin Village in 2012, and Cheryl became chair of its education and cemetery committees, and served on the Board of Directors.

After a decade of managing countless research projects, education programs and historical tours for the Friends of Oberlin, Cheryl used the skills she had gained to focus on the history of her own family. She spent her days online using resources from several of Raleigh’s cultural, genealogical and historical entities.

She received generous help from historians and genealogists at the State Archives of North Carolina, Historic Stagville in Durham, and North Carolina State University. She poured over results from AncestryDNA at night.

Through her research, Cheryl found the names of six generations of family members that she hadn’t learned in her first phone calls for Brooke’s research project. One of the earliest and most important discoveries, thanks to the research of Kathy Staley, was the birth record for Sin’ Tha, her great-great-grandmother, among the Cameron family’s slave ledger.

The collected Cameron Family Papers are preserved at Historic Stagville and the University of Chapel Hill’s Wilson Special Collections Library. Along with the birth records, Cheryl found a bill of sale that recorded 27 enslaved persons being sold to the Cameron family by the Umstead family, a record listing the shoes made by Walker and the laborers who received a pair, and documentation of Margaret Cameron’s inheritance upon her father’s death, totalling $15,000 (more than $500,000 in today’s economy).

As long as Cheryl can remember, there has been a unique treasure hanging on the wall behind their classical staircase. It is a late-18th century portrait of one of Cheryl’s great aunts, Lula, daughter of John Thomspon.

Taken before starting her freshman year at Saint Augustine’s Normal School (now Saint Augustine’s University), the beautiful young woman has a gentle countenance and dark hair hanging down her back. Sadly, Lula fell ill shortly after beginning college and died.

Several months later, Cheryl was cleaning the top of a mahogany armoire in what had been John Virgil’s room when her hand grazed a stack of documents. She pulled them down and there, among the papers, was a photo that appears to be her aunt as a child. The gentle face and dark, wavy hair are nearly the same, and Cheryl hopes research will verify the connection.

After Cheryl’s parents passed away in 2015 and 2017, she started to imagine opening up the family home to the public. “Our family represents an important American story,” she says. “We represent an African American family living a middle-class life. Our story is an inspiration.”

Indeed, while students learn about slavery and the Civil Rights movement in schools, they rarely learn about local Black history. The Turner home is a window into another historic Black experience: newly freed families that built wealth, political power and compassionate community during the Reconstruction period that sustained some families for the next century and beyond.

These Black families survived slavery and the Civil War, but also the Jim Crow Era and segregation. They attended college, built businesses, bought real estate, traveled the world, collected art and lived fulfilling lives into old age. This is the story that Cheryl wants people to hear: her family’s story.

In August, Cheryl formed the Historic Turner House Foundation and Turner House Tours to provide home tours, develop educational materials, host events and fund the home’s preservation.

She envisions bringing in visitors, from school children to international tourists, to understand that the Turner House was built by the hands of the formerly enslaved, and that these people went on to become prominent, successful North Carolinians.

“This home is the physical representation of the untold stories in our state’s history,” Cheryl says. “We want to expand knowledge and offer triumphant perspectives of the American-African experience, before and during the 1800s and early 1900s.”

This year, she hosted landscape design students from North Carolina A&T University as they worked on proposals for Historic Oberlin Cemetery, Historic Morgan and the Historic Turner House. She previously welcomed a class from William Peace University, in partnership with NC State University, to do an archeological dig on land surrounding the home. “Those kids learned what to do in archaeological digs,” she explains. “You don’t have to go to Egypt.

You can learn and uncover great artifacts right here.” And indeed they did. Among their findings were artifacts from the original Oberlin School, started by the villagers shortly after the community was founded.

In a time where many communities struggle with how to teach the past, Cheryl believes everyday citizens will make the difference. “Those of us with important family stories cannot sit idly by,” says Cheryl. “We must open our doors and provide an engaging and supportive way to learn our history. All of it.”

This article originally appeared in the December 2022 issue of WALTER magazine.