The book Biography of a Phantom inspires a journalist to reflect on the ethics of researching musical history.

by David Menconi

I’ve made a living out of writing about music, and, especially over the last few years, digging into its history. I’ve come to learn that anyone who does historical research stands on the shoulders of those who came before, especially when it concerns events of long ago.

Over the five or so years that I was actively researching Step It Up and Go, a history of North Carolina music that was published in 2020, I worked with scores of people who were immensely generous in sharing their knowledge of events that happened before I was even born.

But I also encountered a few folks who were, shall we say, territorial. In particular, I remember one individual who had been researching the 1930s-vintage Piedmont blues scene in Durham — the subject of my book’s second chapter.

This particular person had been doing interviews and research long before I got to North Carolina, and she had plans to write her own book someday. She was extremely helpful at first, sharing some key documents about one of that era’s most interesting figures, J.B. Long.

Long was a store manager who ran a freelance recording operation in Durham in the 1930s. Among the musicians he recorded was the legendary Fulton “Blind Boy Fuller” Allen, a now-legendary figure (and the author of the song that would become my book’s title).

Although Long died in 1975, his grandson was still around when I was researching my book in the late 2010s. But this other person had already interviewed him about his grandfather and asked him not to talk to anyone else, including me. Since she had gotten to him first, she felt a sense of ownership of J.B. Long’s story.

“She feels she has put great effort into this endeavor and asked that I not speak with you,” Long’s grandson told me. “I feel between a rock and a hard place, as I have been working with her for years. However, I have no idea when and if her book will ever come out.”

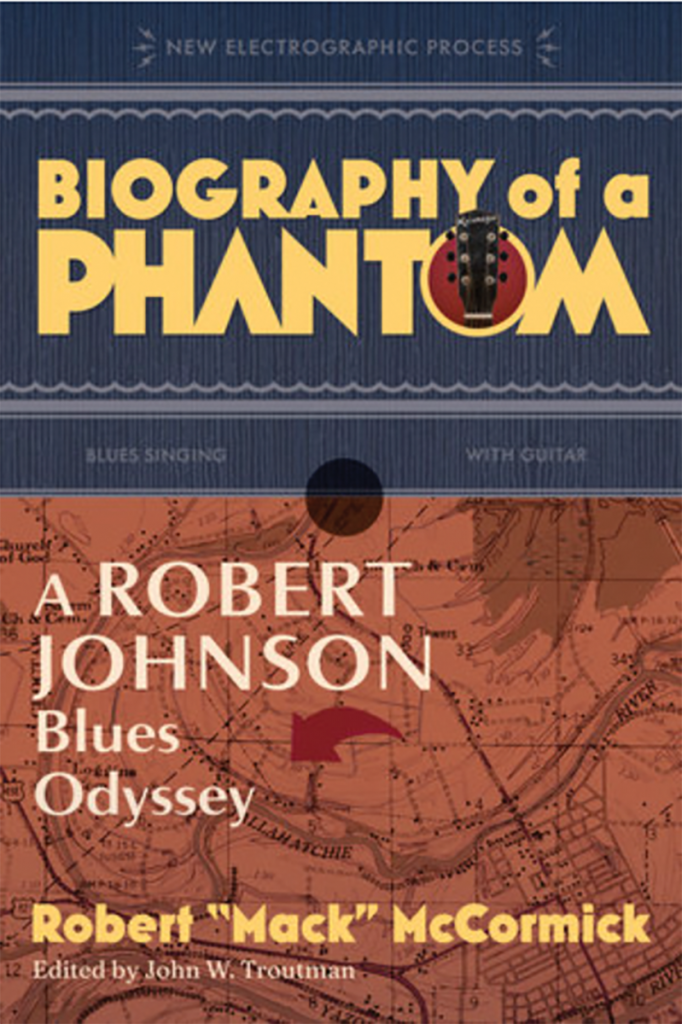

I was reminded of this situation recently while reading a great new book, Biography of a Phantom by the late Robert “Mack” McCormick. The title could refer to the author as much as his subject. Subtitled “A Robert Johnson Blues Odyssey,” it’s an ambitious work about the mysterious life, death and music of the Mississippi blues legend whose heyday was about the same time as Durham’s Piedmont blues peak.

Based in Texas, McCormick was a writer and researcher with an affinity for the blues, as troubled as he was brilliant. It was the 1960s and early ’70s when he took up the story of Johnson, a musician whose work has inspired generations of blues and rock musicians.

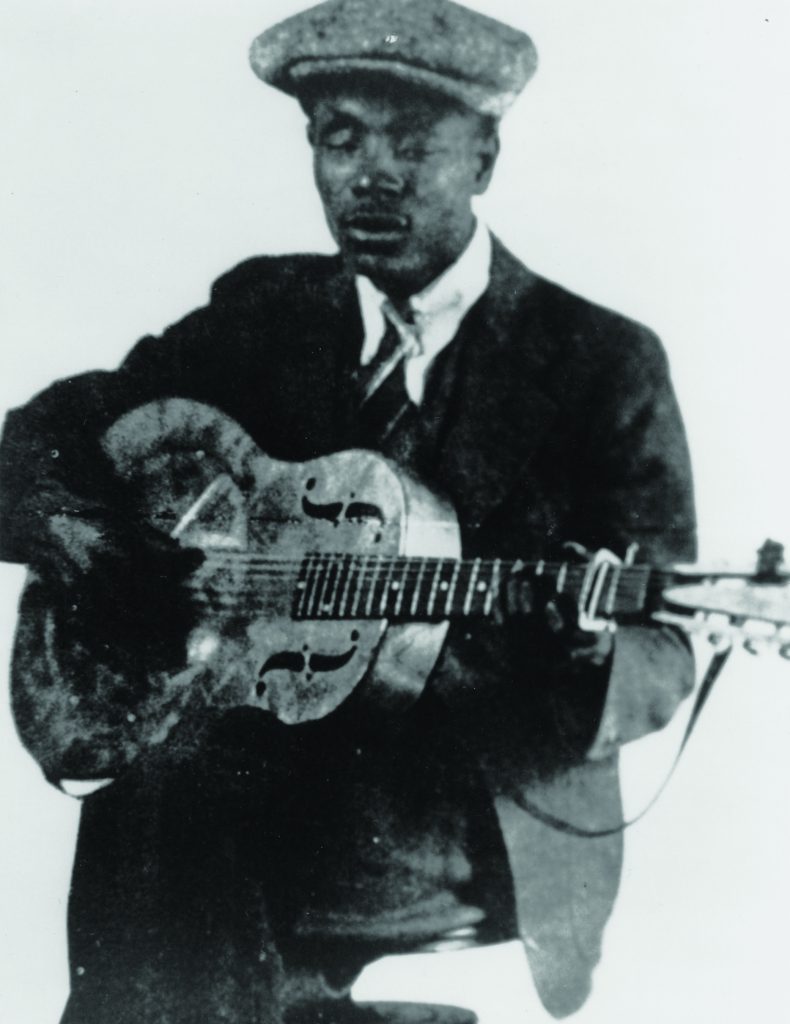

Before Johnson’s 1938 death at age 27 (reputedly poisoned by a jealous husband), the musician wrote and recorded blues classics still heard and widely covered today — “Cross Road Blues,” “Hellhound on My Trail” and “Sweet Home Chicago” among them. The oft-repeated legend was that Johnson had traded his soul for supernatural playing ability in a deal with the devil.

Even though Johnson had been dead and gone for more than three decades, McCormick knocked on enough doors in Mississippi to track down many of his acquaintances and even relatives. He pieced together a credible version of his life and how he died.

The story turned weird and ugly when McCormick succumbed to mental illness and paranoia. He wrote a draft in the early 1970s but could never bring himself to finish it, instead continuing his research. Convinced that rivals in the world of music folklore were going to steal his research, McCormick became a thief himself, making off with a rare photograph of Johnson that he stole from the bluesman’s relatives.

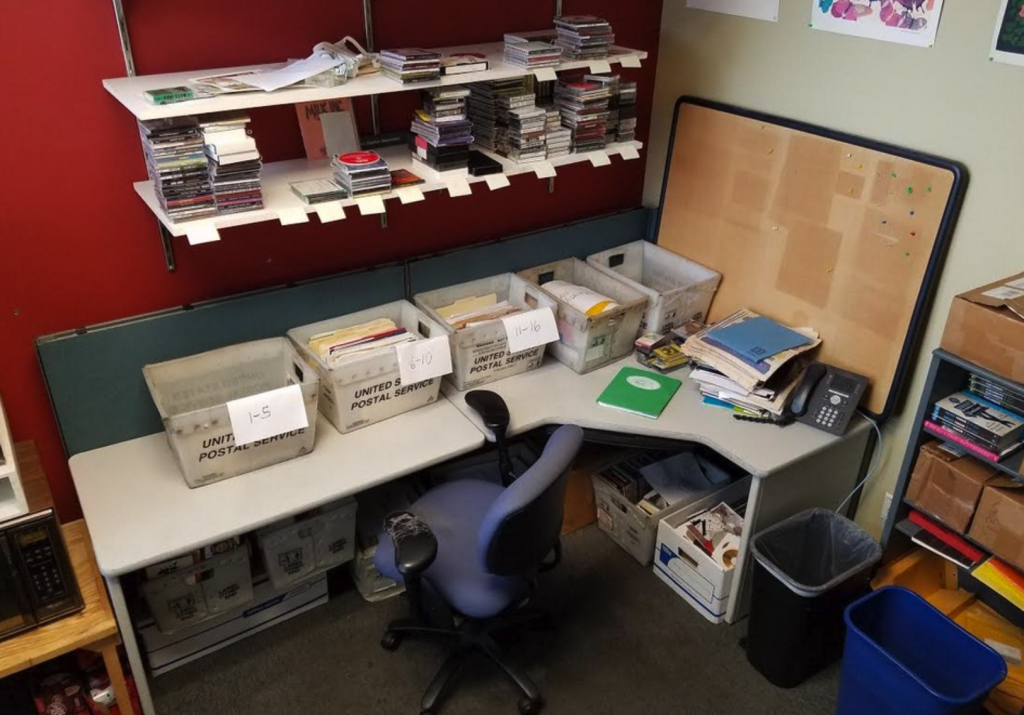

As years turned into decades, McCormick’s Johnson book never appeared — even as his massive research archive, dubbed “The Monster,” grew in size. He even took to inserting fictional red herrings into his own research notes, deliberate falsehoods that would reveal anyone else who tried to use his information without authorization (such as a claim in later years that Robert Johnson was actually from Texas, not Mississippi). McCormick died in 2015, his masterwork unreleased.

McCormick’s monster archive now resides at The Smithsonian in Washington, D.C. The museum commissioned curator John Troutman to pull Biography of a Phantom together from his draft and notes. The book has an introduction and afterword covering McCormick’s story.

But the part of the book that tells Johnson’s story, based on McCormick’s research trips through Mississippi, is fantastic — equal parts biography, murder mystery and cautionary tale. It’s readable enough to be a solid summertime beach book, but it also holds up as history and musicology.

Reading McCormick’s book, and noting the sense of ownership he felt over Johnson’s story, had me reflecting on my own efforts for Step It Up and Go. I finally convinced J.B.

Long’s grandson to talk to me, despite the other writer’s objections. He even provided a wonderful 1930s-vintage photo of his grandfather, which helped personalize this history (see previous page). Meanwhile, that other writer’s book never appeared, and she passed away in 2019. I hope her research is now in the hands of someone who might publish it, and I am still grateful for her help with my own book.

But it made me wonder: When it comes to this kind of music writing and research, who “owns” the story — the first person to uncover it, or the one who’s most likely to bring it to light?

I don’t have a good answer.

This article originally appeared in the August 2023 issue of WALTER magazine.