Yvonne Sanders and Belle Long have become friends as they dig into the past — and reckon with the truth that one’s ancestors enslaved the other’s.

by Hampton Williams Hofer| photography by Joshua Steadman

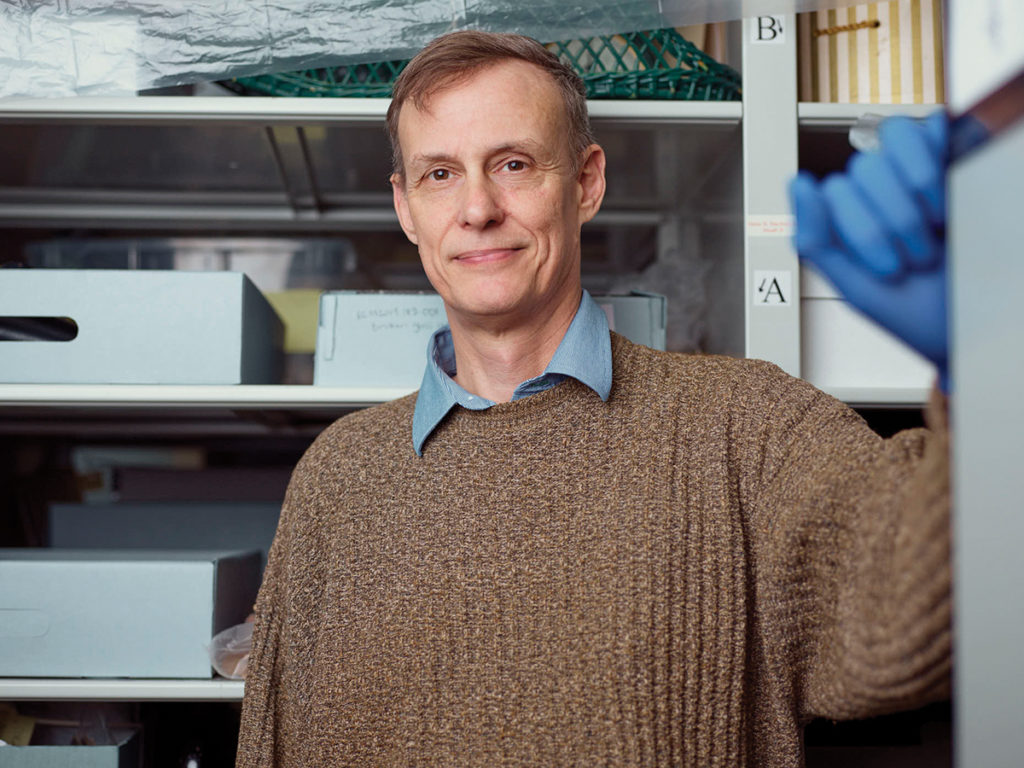

Four years ago, the City of Raleigh Museum received a fund from the Dix Park Conservancy to create an exhibit on the park’s history. The museum’s director, Ernest Dollar, focused initially on Dorothea Dix Hospital: the experiences of the psychiatric patients and the devoted people who worked there.

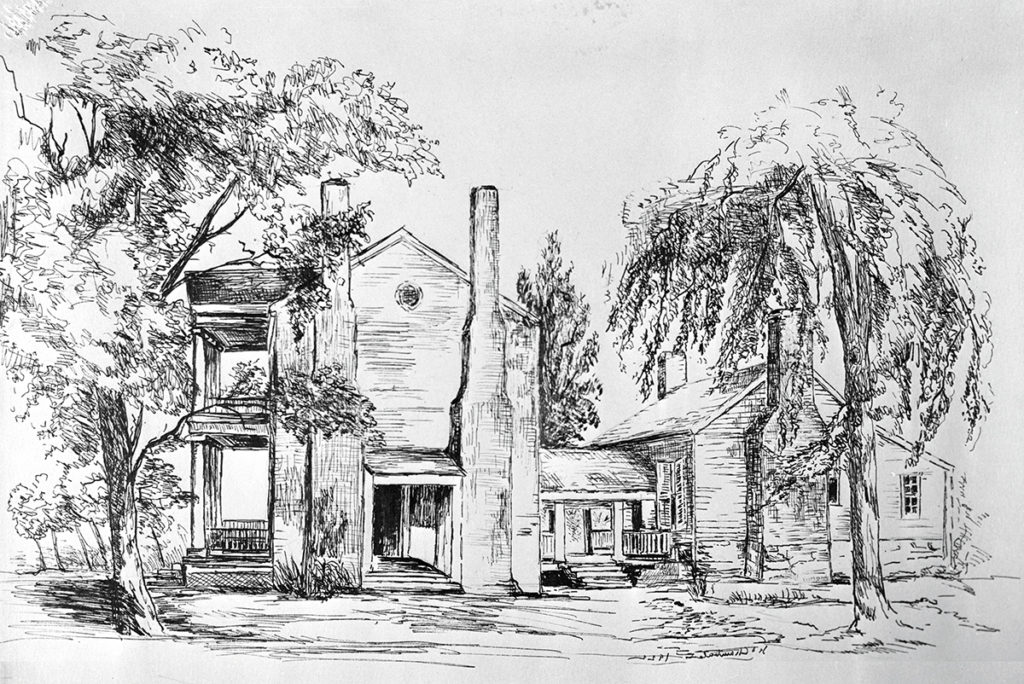

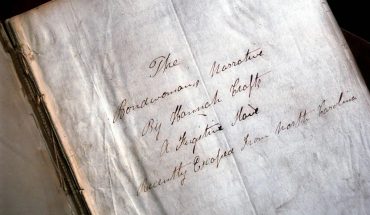

But before Dix was a hospital, its sweeping fields made up Spring Hill Plantation. Its soil holds the legacy of wheat, flax, potatoes, peas and oats — and the sweat of the enslaved laborers who bent over the rows and tilled the land some two and a half centuries earlier. The plantation belonged to Theophilus Hunter, one of Raleigh’s founding fathers, a leader in the American Revolution and prolific owner of both land and enslaved people.

As Dollar dug into the history for his museum’s exhibit, he felt compelled to include the stories of all of the people who had lived on that land. Searching for enslaved workers who may have taken the surname “Hunter” upon emancipation, Dollar combed through the 1870 Census, the first after abolition, and discovered a man named John Hunter, aged 110. According to his obituary, “Uncle John,” as he was known, witnessed America’s birthday in 1776, helped cut down trees to build the city of Raleigh, fought in the War of 1812 and watched the arrival of the Union Soldiers with the freedom they brought.

As Dollar began piecing together John Hunter’s lineage, he says, “the trail kept growing, and I began to find more incredible people in John’s family tree: modern jazz dance pioneers, Tuskegee airmen, politicians and Wall Street innovators. It was truly an American story.”

When the trail arrived at living relatives in New York City, Dollar invited the descendants down to Raleigh to visit the history that their family had helped to create. Twenty-eight of them arrived, many of whom had never met or had long ago lost track of one another. (The City of Raleigh created a short documentary about the project, which you can find on its YouTube channel.)

After John Hunter’s story circulated, Dollar found others in Raleigh who could tie their families back to Spring Hill Plantation. One of them was Yvonne Sanders, who was 16 years old when the Wake County public schools were integrated and has lived in Raleigh all her life. In her retirement, she has found a passion for history, family lineages and reconnection. Her great-great grandfather, Ned Hunter, was enslaved at Spring Hill Plantation around the same time as John Hunter.

When she visits Dix Park, Sanders doesn’t just see a park or playground, she says: “It’s the land where the spirits of many Hunter ancestors still exist.” It conjures memories of her father, who farmed with a mule and plow, just like so many generations of Hunter sharecroppers before him. She thinks of Ned and Maria Hunter, of their six children, and of all the children who have followed.

“I’m extremely committed to tracing our family’s history with as much detail as I can, so we can leave this information for our generations to come,” says Sanders.

Like Dollar, Sanders has found herself enraptured with the seemingly endless trail of lineages from Spring Hill Plantation and the remarkable stories of the people who have come from Dix Park’s land. Along with a team of family members, she is taking part in an effort to track the descendants of each of Ned and Maria Hunter’s six children, the youngest of which is her great-grandfather, Calvin Hunter. The research project has yielded a massive family tree of close to 1,000 descendants reconnected thus far.

“We haven’t even gotten halfway yet,” says Sanders, who is active in the family’s Facebook group and newsletter. It is her family’s hope that sharing their story will inspire other families to begin researching their own. “Though the roads have been long and the obstacles many, each of our Hunter descendants continues to remain resilient,” she says.

Working in genealogy can be an isolating hobby, with hours spent over spreadsheets, searching for old obituaries and chasing leads online. But thanks to Dollar, Sanders found a friend. During Dollar’s development of the exhibit From Plantation to Park: The Story of Dix Hill, he learned that Belle Long, whom he had known through the Wake County Historical Society, was a direct descendant of Theophilus Hunter.

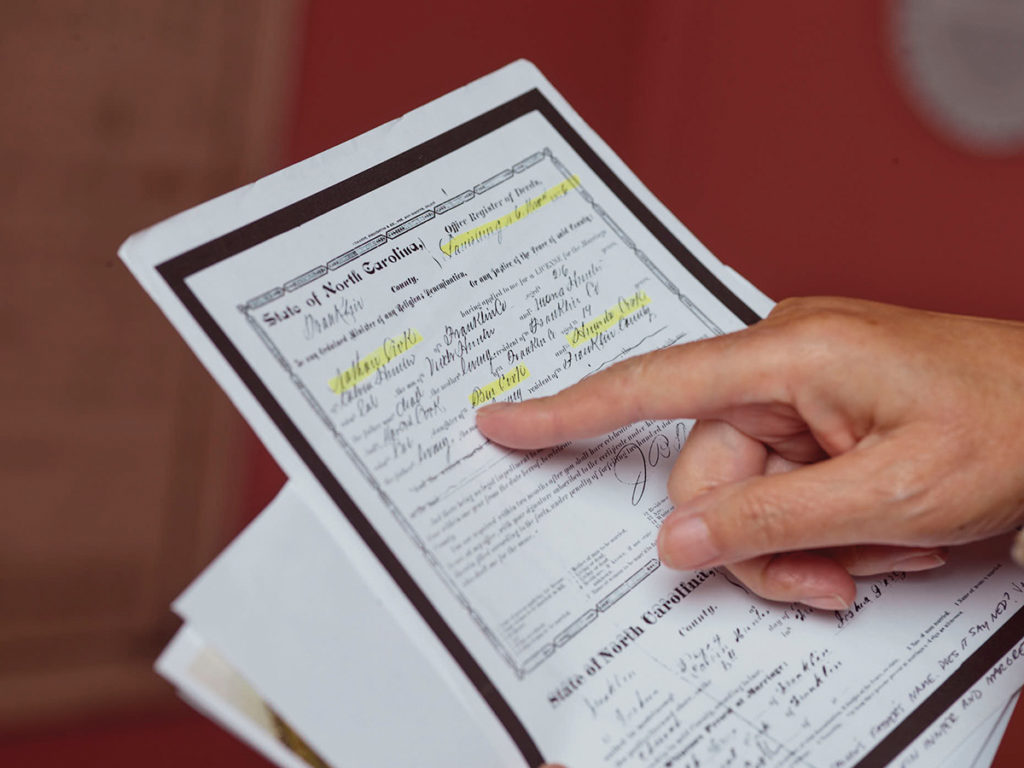

Like Sanders, Long grew up in Raleigh and has resettled here. As a former director of the Joel Lane Museum House, Long is deeply connected to the history of Raleigh. When working as the webmaster for the Wake County Historical Society board seven years ago, she received an email with an inquiry about the possible relocation of Theophilus Hunter’s grave. The grave currently sits behind the original Spring Hill House, which is now the NC Japan Center, and it is one of the oldest marked graves in Wake County. Long, who knew she was somehow related to Theophilus, became interested in the exact connection and started emailing cousins. It turns out she is descended directly from him, her eighth great-grandfather. “Not only did I look into Theophilus Hunter, but also the enslaved people who lived there. I began to produce a giant spreadsheet with everything I could find on these people and what happened to them,” says Long. The initiative snowballed from there.

In June 2021, Dollar introduced Long to Sanders. The two emailed that whole summer and are now regularly in touch, texting and meeting for coffee. “We have become research partners and friends,” says Sanders. “This kind of research is independent, but it’s great to have someone like Belle to partner with.”

They have been able to help each other in their pursuits: Long discovered Theophilus Hunter’s 1798 will in the public record, which she shared with Ned Hunter’s descendants. Theophilus Hunter left 60 enslaved people to various family members. Knowing Ned Hunter’s name has been a vital clue for Sanders and her relatives as they trace their lineages.

“It was our mutual passion for family history and the pursuit of social justice that initially connected us and binds us together,” says Long. It is a complicated friendship: the truth remains that one of their ancestors enslaved the other one’s ancestors.

“I have mixed emotions,” says Long, “because I regret what my ancestors did to Yvonne’s ancestors. But it happened. And I can’t change that. All I can do is look to the future and try to make connections.” It’s a skill she has acquired, and it is what she loves: helping people find their ancestors and discover where they came from. “It gives anybody a sense of who they are,” says Long, “if you understand the past, perhaps we as a society won’t make the same mistakes in the future.

These stories are so important. My friendship with Yvonne is one way to build a connection on a micro level.” Sanders and Long have served together on Dix Park’s Legacy Committee, which seeks to honor the history of the land and its human history.

Susan Garrity, chair of the Legacy Committee, says that while many people know of the park as the site of Dorothea Dix Hospital, many are unaware that the Spring Hill Plantation preceded the hospital. “The Legacy Committee is engaged in discovering, honoring and memorializing these human histories,” she says. “Remembering and learning from the past was a key criterion behind the city’s decision to join the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience.”

As a registered Site of Conscience, Dix Park is considered an interpreted place of memory. “Legacy Committee members like Yvonne and Belle are actively engaged in connecting the past to the present. The City’s recent undertaking of a Cultural Interpretive Plan for the site emphasizes its commitment to honoring the human legacies of the land by telling their complete stories,” Garrity says. For Dollar, it’s been a highlight of his career: “Rarely does a museum, or a historian, stumble into a discovery that is as impactful or meaningful as our work with Dix Park.”

Sanders credits two cousins for her involvement with the Legacy Committee and her newfound passion for genealogy: Demetrius and Mario Hunter. Demetrius Hunter was first on the Sites of Conscience Committee and was tasked with gathering family members to help come up with a plan for a proper memorialization of the family at Dix Park. Mario looped in the cousin he knew had both the time and knowledge to carry the initiative forward: Yvonne Sanders.

In her genealogical work, Sanders found that several of the descendants of Ned and Maria Hunter went on to work at Dorothea Dix Hospital, likely with no notion that they were walking the same ground their ancestors had plowed.

The land has gone from a hunting and gathering ground for Native Americans, to a settlement by colonists, to a thriving plantation, a pioneering psychiatric hospital and soon a 308-acre city park for everyone. Dix Park is a gem for the city of Raleigh in part because of what it promises, but perhaps even more so for the story it tells: one of abundance, suffering, connection and working toward redemption.

right: Cheryl Hunter, Leon Hunter (seated), Bolithia Etheridge, Kelly Dunn, Gail Dunn (seated), Hope Fryar, Betty Baker, Peggy Hunter (seated), James Hunter, Yvonne Sanders (on ladder), Roger Hunter, Robert Hunter, Shirley Hunter (seated), Pamela Jackson, Donald Gatling (seated), Sharon Gatling

This article originally appeared in the February 2023 issue of WALTER magazine.