In honor of Women’s History Month, take the time to learn about these brave and intelligent women who directly impacted Raleigh.

by Jamaul Moore

Have you ever heard of Isabella Cannon, Juliana Royster Busbee or Getrude Cox? These women made history right here in Raleigh for their contributions to academia, politics and science. Some of these names have made it onto parks or library walls — but for each, there’s more to the story that can be summed up on a plaque. Learn more about 12 inspiring women who helped Raleigh make it what it is today.

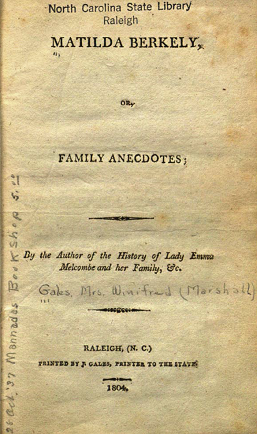

Winifred Marshall Gales (1761 – 1839): First North Carolina Woman to Have Book Published

Originally born in Newark, England in 1761, Winifred Marshall Gales emigrated to America after her husband was forced to flee from England for his reform activities. At first taking residence in Philadelphia, she and her family settled in Raleigh in 1799. In 1804, she wrote Matilda Berkely; or, Family Anecdotes, which is considered to be the first novel published by a resident in North Carolina. The book is based on Gale’s own recollections of her family through the fictional character Matilda, specifically the great distance between her family in England and her new home in America. Reviewers of the book found the book typical of written work in the latter half of the 18th century by English authors, detailing their experience in the period of the American revolution. Her family were firm believers in tolerance and Unitarianism, and moved to Washington, D.C. in 1833 due to difficulty maintaining and growing orthodoxy in North Carolina.

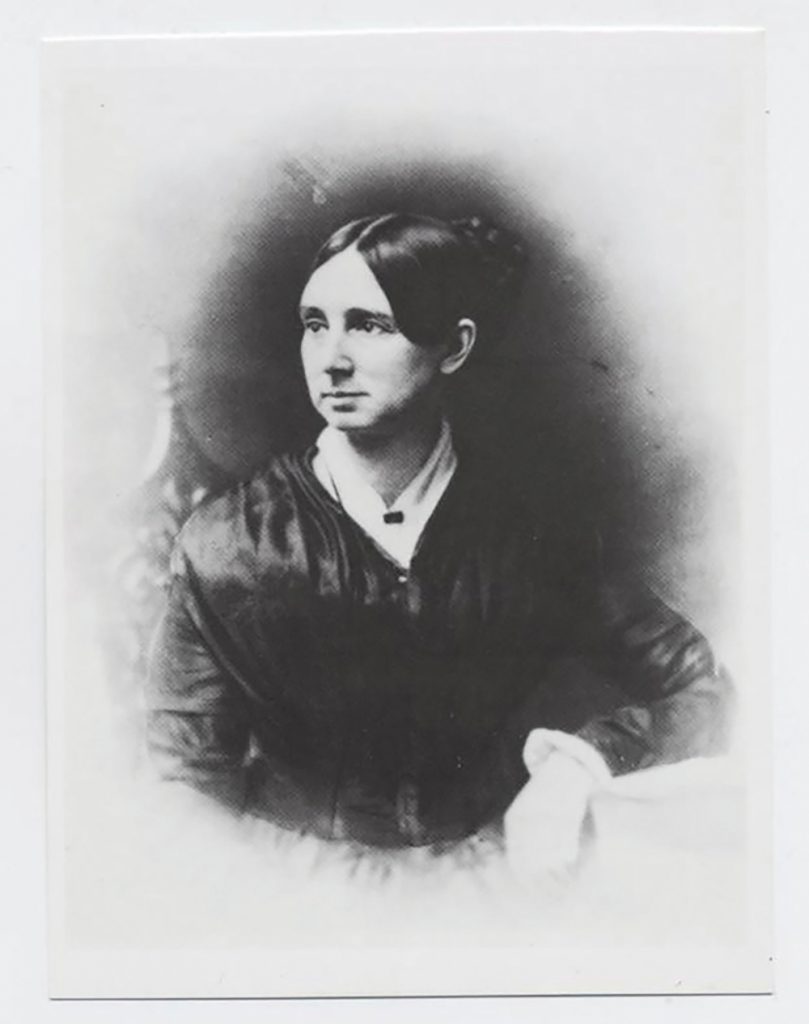

Dorothea Dix (1802 – 1898): Champion for Mental Health

While neither a native of Raleigh or North Carolina, Dorothea Dix became a local resident and advocate for those struggling with mental illness whose influence can still be seen in Raleigh today. In 1841, while teaching Sunday school at the East Cambridge Jail in Massachusetts, Dix witnessed the deplorable treatment that prisoners endured at the hands of staffers, particularly those who were mentally ill. She went to court and secured an order to have heat provided for the prisoners, as well as other living improvements. Her work did not stop in Massachusetts, as she led a campaign to establish human mental asylums across the United States, including in North Carolina and South Carolina. After venturing to Europe, her efforts in enacting social reform led to the construction of new hospitals for the mentally ill on orders from Pope Pius IX, upon her discovery of the disparity between public and private hospitals. In 1848, she came to North Carolina, where she helped establish Dix Hospital, the first psychiatric hospital in the state, in 1856. As knowledge about mental health and psychiatric disorders has improved in the decades since, the building and grounds have been transformed into a public park.

Mary Jane Patterson (1840 – 1894): First African American to Earn a Bachelor’s Degree in the United States

The daughter of slaves, Patterson was originally born in Raleigh in 1840 and lived there for 16 years before she and her family settled in Oberlin, Ohio in 1856. She later attended Oberlin College and became the first African American woman to earn a BA degree in 1862. During her time at Oberlin, Patterson took classes that were primarily designed for men, such as Greek, Latin, and high mathematics. From 1869 to 1871, Patterson taught in Washington, D.C. at the Preparatory High School for Colored Youth, now known today as Paul Laurence Dunbar High School, and would serve as the school’s first Black principal from 1871 to 1872; she was reappointed in 1873 until her resignation in 1884. During Patterson’s tenure, the school became known as a prestigious institution for secondary education. Patterson’s work extended beyond education: she was also involved in advocating for women’s rights, helping to establish the Colored Women’s League in Washington, D.C.

Anna Julia Cooper (1858 – 1964): First African American Woman to Earn a Master’s Degree

Born into slavery in 1858, Anna Julia Cooper decided to pursue a college degree after the death of her husband, George A.G. Cooper. She attained a scholarship and, like Patterson, attended Oberlin College in Ohio, one of first colleges to admit African Americans, and in 1837, the first to admit women. Cooper earned her BA in 1884 and eventually her master’s degree in mathematics in 1887, becoming the first African American woman to earn a master’s degree. Before attending Oberlin, she enrolled at Saint Augustine’s Normal School and Collegiate (now Saint Augustine’s University) in 1868, a school for freed slaves, where she discovered her male classmates were encouraged to study a more rigorous curriculum than female students. This motivated her to advocate for the education of Black women well into her adult years. In the 1890s, Cooper often spoke publicly on the idea that women had a moral duty and responsibility to transform public policy, particularly education. She addressed various groups, including the National Conference of Colored Women and the Pan-African Conference. She would eventually be named principal at the historic M. Street High School in Washington, DC, where she helped enhance the school’s academic reputation, as well as seeing several graduates attend several Ivy League schools.

Juliana Royster Busbee (1876 – 1962): Advocate of Artistic Tradition and Pottery

Born in Raleigh in 1876, Busbee held a passion for art for most of her life, studying art and photography at Saint Mary’s Junior College (now Saint Mary’s School) and became the art department chair of the Raleigh Women’s Club, a community volunteer service supporting a variety of activities including arts & culture, in 1911. In her role, Busbee promoted handcrafted traditions and artistic creativity. Eventually, she, along with her husband, Jacques Busbee, established Jugtown Pottery in Seagrove, an area known for its pottery. Along with her husband, Busbee is credited for reviving the pottery industry, with tourism rebounding during around 1920 and again from the 1950s through 1970s. By 1982, a group of local potters would establish the North Carolina Museum of Traditional Pottery and would eventually organize the Seagrove Pottery Festival, held each year before Thanksgiving. Aside from her work at Jugtown, Busbee was also active in civic affairs. She was a charter member and vice president of the State Art Society and became an honorary life member of the North Carolina Literary and Historical Association. On May 31, 1959, the Woman’s College awarded her an honorary degree of L.H.D.

Carrie Lougee Broughton (1879 – 1957): First State Librarian in North Carolina

You may recognize this famous last name from Needham Broughton High School in downtown Raleigh, but his daughter is noteworthy in her own right. A Raleigh native, Broughton was born on September 16, 1879, and was named the State Librarian, making her the first woman to serve as State Librarian, as well as the first woman to serve as head of a state department in North Carolina. Her work included establishing a genealogical collection through the State Library’s Department of Cultural Resources, which covered deaths, marriages and descendants of early North Carolinians. She remained in her position until her retirement in 1956 and died a year later.

Beulah Louise Henry (1887 – 1973): Pioneering Inventor

Known as “Lady Edison,” Beulah Louise Henry was born on September 28, 1887 in Raleigh, and was the granddaughter of former North Carolian governor W.W. Holden. She received her education at Elizabeth and Presbyterian College in Charlotte, where she applied for her first patent in 1912 for a vacuum-sealed ice cream freezer. In 1924, Henry moved to New York City to continue working as an inventor, where she established two companies that same year — Henry Umbrella and Parasol Company and the B.L. Henry Company — and served as a consultant for manufacturers. Among her other inventions were a lockstitch bobbinless sewing machine, a “protograph” (which produced four typewritten manuscripts at a time without the use of carbon paper) and a “Miss Illusion” doll that changed its eye colors at the push of a button. In total, she had 49 patents and over 100 inventions by the time of her death.

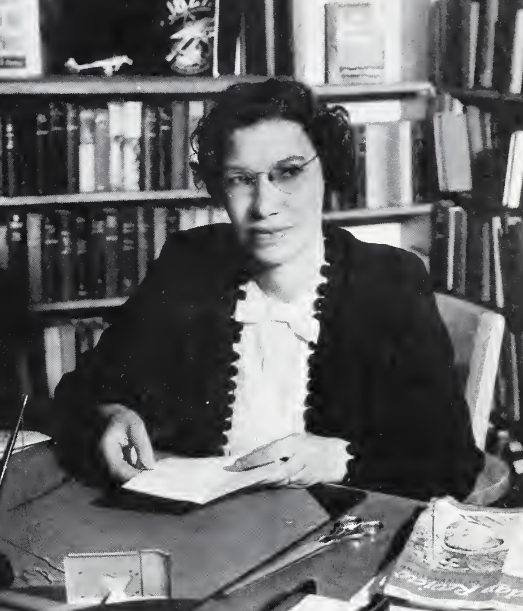

Gertrude Cox (1900 – 1978): Founder of NC State’s Statistics Department

If it weren’t for Gertrude Cox, North Carolina State University’s Statistics department wouldn’t be what it is today. Cox was born in 1900 in Dayton, Iowa, where she studied mathematics at Iowa State College, earning her B.S. in 1929, and later her master’s degree in statistics in 1931. From 1931 to 1933, Cox attended the University of California at Berkeley, undertaking her graduate studies in psychological statistics before returning to her alma mater to establish Iowa State College’s new Statistical Laboratories, where she worked on design of experiments. In 1940, she was appointed professor of statistics at North Carolina State College in Raleigh. In the same year, she founded the institution’s Experimental Statistics department, which is regarded as the first in the United States. With her position in the statistics department, Cox advocated for statistical analysis and up-to-date computing out of her desire for the facility to be at the forefront of statistical software. Her influence would inspire Raleigh statisticians to develop the initial SAS programs we know today. In addition, Cox worked on the creation of the Research Triangle Park and was the first female elected to the International Statistical Institute. She was also the president of the National Statistical Association, earning her the title, “First Lady of Statistics.”

Isabella Cannon (1904 – 2002): First Woman to Serve as Mayor of Raleigh

Isabella Cannon was originally born in Dunfermline, Scotland on May 12, 1904, before she and her family emigrated to the United States when she was 12. Prior to her election, Cannon never ran for political office. In her early years, she was a high school teacher at Winecoff High School and served as the director of Elon College’s weekday experimental school of religious education from 1925 to 1928. In 1954, she became the director of the North Carolina State University library, a position she held for fifteen years. Cannon became the first female mayor of Raleigh, defeating then incumbent mayor Jyles Coggins in 1977 at the age of 73. She served one term, until 1979, but during her tenure, she led a comprehensive growth plan used to guide development for the city that has been used through the 21st century, well after she left office. In 1978, she was awarded an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from Elon University. She would receive other accolades and honors throughout her life, including being elected to the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 1998 and awarded the Order of the Long Leaf Pine by then-Governor Jim Hunt for her service to North Carolina. In 2011, the city of Raleigh dedicated the Isabelle Cannon Park, formerly the Gardner Street Neighborhood Park, in honor of her legacy and service.

Mollie Huston Lee (1907 – 1982): Founder of First Library to Serve African Americans

Mollie Huston Lee was born in Columbus, Ohio in 1907 and moved to Raleigh in 1930 after graduating from Columbia University. She worked as a librarian at Shaw University, and during her five-year tenure, she recognized the need among African Americans in the surrounding community for black literature through the public library system. At the time, Raleigh did not extend access to public libraries to African Americans. In 1935, Lee opened a small storefront on East Hargett Street in the Delaney building, with a collection of 890 books, becoming the first black librarian in Wake County. In the same year, she met with mayor George A. Wisley to discuss the creation of a library that served African Americans, which would be established as the Richard B. Harrison Library on November 12. Her community outreach in public library services expanded to Wake County and brought the library to individuals who could not go there themselves. This included offering library books to local businesses and patients at nearby medical centers, including Saint Agnes Hospital. Among the library’s programming was providing educational and recreational tools to children to help them in their formation as good citizens in their community. In addition, she served as supervisor Negro School Libraries of North Carolina from 1946 to 1953, earning her the moniker the “librarian’s librarian.” She retired on June 30, 1972, with a career spanning 42 years in public service.

Kate Adams (1919 – 2002): Military Pilot During World War II

Kate Adams was born in Durham in 1919, and for most of her early life, she held a deep passion for aviation. By the time she began her studies at Duke University, she took a Civilian Pilot Training course, in which only one woman was accepted for every ten men. To complete her course, she traveled from Durham to take flying lessons in an airfield in Raleigh while maintaining her studies. By the time she graduated in 1941, Adams had attained a degree in fine arts, as well as a private pilot’s license becoming a part of the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP). After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Adams piloted various military planes and served as an instructor for flight cadets. Adams as well as other members of the WASP were largely unrecognized by the general public and the government during their service, but finally attained wider recognition for their service and contributions before she passed away. On March 10, 2010, the WASPs received the Congressional Gold Medal in a ceremony for their military service during World War II.

Millie Dunn Veasey (1918 – 2018): Civil Rights Advocate

Born in Raleigh in 1918, Veasey enlisted in the only all-female, all-Black unit of the military during World War II, the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion in December 1942. After returning home, she became the first female president of the Wake County chapter of the NAACP. In 1963, she helped organize a bus trip for the march on Washington with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr in Washington DC, and had a front-row seat to his “I Have a Dream” speech at the Lincoln Memorial. In addition, she participated in sit-ins through the Raleigh area in an effort to integrate lunch counters and in 1966 she helped arrange Dr. King to visit the Raleigh area, his second visit to the state after speaking at Needham B. Broughton High School in 1958. Her legacy helped change the perception of women of color and their capabilities, both during war and the civil rights movement.

This article was originally published on March 16, 2023 on waltermagazine.com