On damp nights in the winter in North Carolina, a mating ritual surfaces where thousands of salamanders gather to lay eggs.

words and photographs by Mike Dunn

On a cold and rainy winter’s evening, most of us prefer to huddle in a blanket by a fire with a hot drink. But if you have the right habitat nearby, I encourage you to bundle up, put on your rain gear, and head outside with a flashlight.

That’s because on any wet night from January through March here in the Piedmont, you might get to experience a breeding congress — when a group of salamanders gather to reproduce. The most notable species in our area is a large (up to 8 inches long) dark amphibian with bright yellow or orange spots, aptly named the Spotted Salamander, Ambystoma maculatum. They typically breed in vernal pools, areas that fill with water in the rainy season and dry up in summer. Most of the year these salamanders are largely hidden from view. They live in the woods, inhabiting underground burrows or hidden under logs, and occasionally venture out at night to feed on earthworms, snails, and other prey. But during their breeding season, they migrate to nearby fishless pools, often the same ones where they hatched, for an amazing courtship ritual.

My first encounter with a breeding congress happened when I moved from Raleigh to rural Chatham County. One February evening, I was driving home in a heavy downpour when my headlights picked up something slowly crawling across the road. I swerved, not sure what it was, then saw another something a few feet away.

I pulled over and got out. Salamanders! I could see five Spotted Salamanders all heading in one direction and, unfortunately, found two that had been squished by cars. I grabbed my umbrella and a flashlight and traipsed into the woods. About 50 feet in was an elongated gash in the earth, maybe 6 feet at its widest and probably 30 to 40 feet long. I peered into the water and could see a few salamanders swimming about. It had not been raining long, so this was early in the process.

I called two friends that I knew would want to see this, and it started raining even harder — that was good, as the heavier the rain, the better for the migration. Soon, there were several more salamanders crossing the road, and the pool was swarming with the spotted beauties.

We watched in awe for several minutes, then decided to station ourselves out on the road to try to help salamanders cross. Luckily, this stretch is not heavily traveled, but the rain occurred when most people were returning home from work, so it was going to be a tough night for these amorous amphibians. Whenever we saw a car approaching, we would scurry around getting any salamanders we could see safely across.

This became a ritual for a few years on any rainy winter night that we thought might be a good salamander night, especially if the rain was early in the evening. I guess it was a bit odd for drivers to see people out along the road waving their flashlights around in pouring rain. One night, a sheriff’s car pulled up, cracked a window and said someone had called them to investigate what was going on. He asked what I was doing and I excitedly showed him the salamander in my hand and explained. He looked at me, shook his head, rolled up the window and drove off. I’m not sure I convinced him of the value of my pursuits.

During the breeding frenzy, male salamanders deposit specialized structures, called spermatophores, on the bottom of the pool. At first glance, these look like bird droppings littered about on the leaves in the pool, about a half-inch tall, with a clear, gelatinous base and a multipronged, whitish stalk on top of which is a cap containing the sperm. A female picks up sperm from the cap, which internally fertilizes her eggs. Two to three nights later, she lays her egg mass, usually attaching it to underwater vegetation or a twig. The jelly-like blobs contain 50 to 200-plus eggs surrounded by a gelatinous matrix, and she may lay two to four egg masses per season. The masses start a little bigger than a golf ball but can swell to the size of a softball over the next several days with the absorption of water.

The egg masses take about six to eight weeks to hatch, depending on the temperature. Over time, most eggs take on a greenish color as they’re colonized by a green algae, Oophila amblystomatis (the scientific name means “loves salamander eggs”). This symbiotic relationship has been observed for over a hundred years; these algae only grow in eggs of this salamander species. The algae get nutrients like nitrogen and the developing embryos get oxygen out of this union. Several years ago, scientists discovered the algae inside the cells of adult female salamanders, the first time a symbiotic relationship had been found between an alga and a vertebrate, leading one researcher to dub them “solar salamanders.”

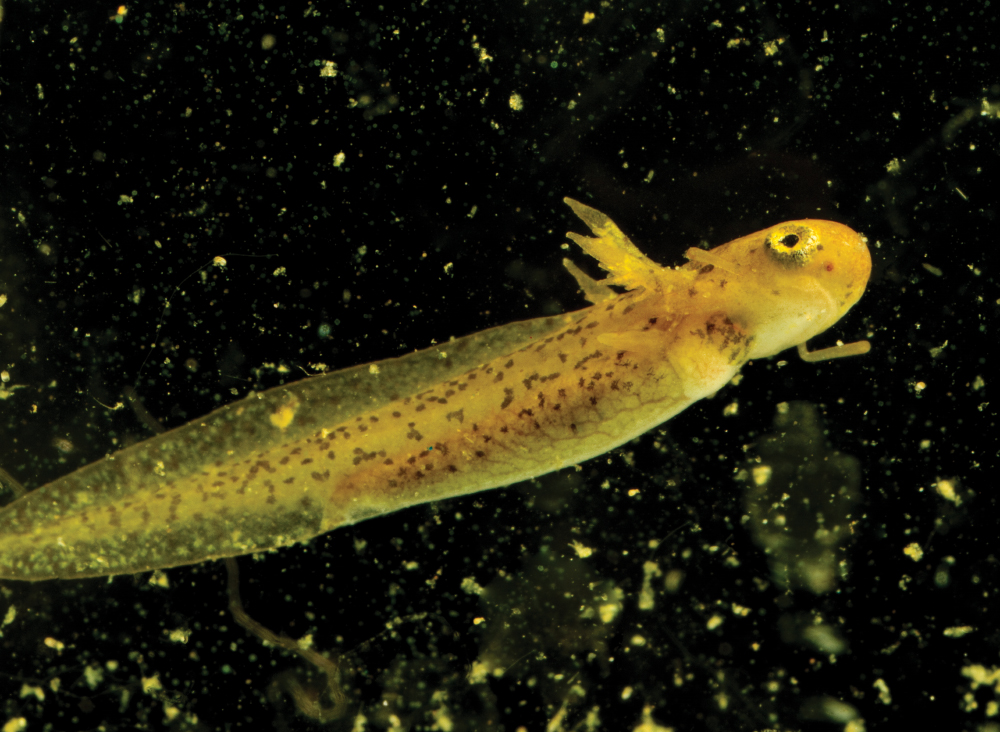

The jelly blob starts to break down as hatching approaches. When a larva pokes through its egg, it is slender, just shy of an inch long, with branched, feathery structures on its head — external gills used to breathe underwater. The larvae grow rapidly, feeding on a variety of small invertebrates (zooplankton, mosquito larvae, etc.). They, in turn, are eaten by a variety of predators (other salamander larvae, giant water bugs, dragonfly nymphs). Few make it to maturity. By summer, the external gills are reabsorbed and larvae transform into juvenile salamanders (called metamorphs — a nice name for your teenagers at home perhaps). Soon, they leave the water and head for their woodland homes. In a year or two, they will migrate to a pool and start the cycle anew.

Spotted Salamanders are found statewide, though somewhat scattered on the coast. Luckily, there are several places on public lands in our area where you can observe the egg masses and learn about these beautiful creatures, including Hemlock Bluffs and Swift Creek Bluffs Nature Preserves in Cary, Harris Lake County Park in Wake County, several locations in Duke Forest, and the North Carolina Botanical Garden in Chapel Hill (some offer programs highlighting these amphibians). If you have sufficient upland habitat nearby (ideally hardwood forest), you may be able to attract salamanders (and certainly other amphibians) to your property by creating fishless pools with hard plastic pools or pond liners. We have two such water gardens near our house that have hosted numerous salamanders and frogs for many years.

The next cold, rainy night we have, let your thoughts turn to salamander love, and wish them well in their romantic endeavors. Or better yet, if you have suitable habitat nearby, gear up, get outside, and see if you can find any amorous amphibians yourself.

__

This article originally appeared in the February 2022 issue of WALTER.